March 18, 2009

Conversing with Digital Texts?

There’s a lot of fuss and bluster in book circles about digital book technology like the Kindle which I am not going to weigh in on in any serious way because I have not actually ever handled an ebook reader and I am not entirely sure what capabilities they do and do not have. That said, I was sorting my books yesterday (something which happens on a semi-regular basis, as it brings me great pleasure) and wondered how I would replace my written “tags” if I were to convert for whatever reason to an entirely digital library. The Kindle has a little keyboard on the bottom, I see; while my mother confesses to printing out pdfs of texts in order to annotate them. Neither of these solutions entirely appeals to me.

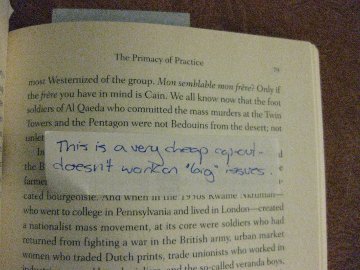

Most diligent readers keep track of their thoughts on a text as they read. The most common habit these days is to keep notes in the margins of a book, creating a gloss to the text that is referred to as “marginalia”. I find attitudes towards marginalia vary significantly between readers.My own opinion is that unless you are or are intending to become Samuel Coleridge that you should keep your notes in a book to a minimum, but my squeamishness towards defacing books doesn’t seem to be shared by the legions of bold, ballpoint-pen-bearing readers that populate, especially, academic libraries. Yes, the marginalia of great readers and writers can be fascinating, and a source of some really excellent criticisms on a text. But I can’t stand the unintelligible scribblings of former readers scaring my book’s pages, and I do future readers the favour of keeping my opinions out of their text as well. But that’s just me.

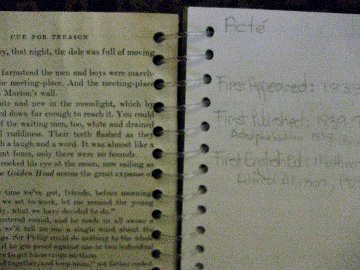

That isn’t to say that I don’t keep conversation with my books. I waver between two techniques, though one is more of a bad habit than the other. The first, the bad habit, is to note my commentary on little scraps of paper that I leave marking the pertinent page. Many of my books are marked with enough of these little scraps that they look like they’ve got little paper pigtails. This leaves my books clean, and certainly helps me find important pages quickly. But unfortunately my notes also tend to slip out of their books, leaving important passages forever lost. I spent too many hours out of last month trying to find a quote from Robertson Davies on the importance of reading Dumas to young boys that I *swore* I’d marked. This is, however, something which margin-scribblers must struggle with as well. Knowing you’ve seen something somewhere isn’t enough of a roadmap to finding a note in a library of books.

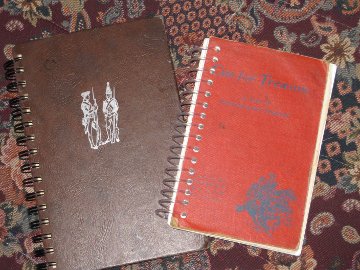

My other habit is to keep a notebook at the ready while I am reading, my loci communes. This is an old practice with pedigree and some wonderful perks. Not only can you look back to what you were thinking when you read a book, but you can organize your notes however you like – perhaps keeping a section for favourite quotes, another for future writing ideas, or collections of information pertaining to specific subjects. Writing an essay on Emerson? Maybe you’ve been keeping a notebook of thoughts and quotes pertaining to Emerson, that roadmap to your library. But open-ended organization of your thoughts isn’t the only benefit, nor is the fact that your books will stay fresh and clean. These notebooks become wonderful additions to your library.

Me, I am a sucker for snazzy little notebooks. I’ve been drawn to blank notebooks ever since I was a kid. They were pre-bound novels in potentia. A story handwritten in a notebook was automatically a published book, thought eight-year-old me. And weren’t spell books in all the stories just handwritten books of arcane recipes? These days I buy notebooks with almost as little restraint as I buy books because Toronto seems to be overflowing with talented paper artists. I’m especially partial to these little numbers: notebooks made from recycled old novels. Even a dedicated book hoarder like me has to admit that there comes a time in a book’s life when it has no future except in the recycling bin – but wait! I’ve seen these journals called “upcycled journals” – you can even get ones with old board games (Scrabble, anyone?) or VHS slips for covers. How cool is that?

Maybe the biggest perk of my loci communes is that, in any future ebook apocalypse, they remain useful and relevant. The electronic versions of marginalia and tagging still have their shortfalls over the real thing. Scanning a book for the visual cues notes and tags offer becomes difficult. Search functions rely on memory, rather than aid it. And does an electronic scroll have the margin space available for good notes? Perhaps they could (or do?) offer a function to watermark notes over the text – hell, they could allow you to save the annotation as a separate file to overlay any copy of your book. Torrents of professional annotation, anyone? Forgeries of celebrity marginalia? There’s leeway for some interesting speculation here.

But none of it makes me feel quite as secure as knowing that, in the event that I were trapped in a world with only an ebook reader and a good craft fair circuit, I could still furnish a library of worn cloth covers, good paper and sewn bindings, filled with the memories and impressions of a lifetime of reading. It certainly beats sheafs of unbounded printed pdfs!

March 17, 2009

Tangential to A History of Reading

This year for a myriad of reasons, I have chosen to read books by Canadian authors exclusively. I had considered opening this blog with a post explaining my decision, but I found the post dull and reasoned that you readers might also. So I will skip onwards and upwards to a tangential point.

I do not intend to review the books I will read. I am not a literary critic or even a student of literature; I certainly approach books critically in my own way but feel I don’t have the critical background to do justice to the pursuit. I am, on the other hand, a prolific reader with a lot of background in a number of other disciplines. So what I propose to do in lieu of a review is to offer a thought (or two, or three…) relating to what I’ve just read. The thought might be critical, might be beside the point, or might simply be something else that the book made me think of. What it won’t be is an evaluation of the book on the whole – that has been done and will be done at length by other people who have a better idea of what they are doing.

The point I want to pursue from Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading will probably speak volumes about why I am not a student of literary theory, since I know what I am about to suggest usually makes actual students of literature turn a bit red and wonder if maybe I’m a philistine. If you’ve read the book (and if you’re a once or future student of literature, I bet you have – it is a favourite on undergraduate syllabi), you’ll find the bit that got stuck in my craw on page 92 & 93. “The limits of interpretation coincide with the rights of the text,” Uberto Eco tells us, and in this case we’re told that Kafka’s “multilayered text” has inspired some 15,000 works of criticism, while the lighter works of, say, Judith Krantz only allow “one…airtight reading”.

The point I want to pursue from Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading will probably speak volumes about why I am not a student of literary theory, since I know what I am about to suggest usually makes actual students of literature turn a bit red and wonder if maybe I’m a philistine. If you’ve read the book (and if you’re a once or future student of literature, I bet you have – it is a favourite on undergraduate syllabi), you’ll find the bit that got stuck in my craw on page 92 & 93. “The limits of interpretation coincide with the rights of the text,” Uberto Eco tells us, and in this case we’re told that Kafka’s “multilayered text” has inspired some 15,000 works of criticism, while the lighter works of, say, Judith Krantz only allow “one…airtight reading”.

What this brought to mind was one of the aspects of David Adams Richards’ Mercy Among the Children that really drove me nuts. In Mercy we meet Sydney, the pacifistic father of three who is venerated in the eyes of his eldest son as some kind of saint, in equal parts because of his honesty and because of his literacy. Sydney, you see, if a self-taught prolific reader who, with no outside input whatsoever, has happened into literary tastes comprised of Western Canon favourites like Tolstoy, Milton and Camus. Despite being entirely alienated from the literary and academic world he has read and understood all that world would have had to offer him.

The idea that any literary work is can be self-evidently superior to another is a bit boggling to me. Yes, of course some works have more depth and withstand the critical readings of an experienced and educated person, but is the presence of those depths an a priori truth that anyone of sufficient intelligence will notice? If you give Swift to an uneducated man living on a desert island, will he necessarily see it as a work of social commentary, or might he be forgiven for thinking it was just an entertaining bit of fantastic adventure?

We’re told in Mercy that Sydney has received the bulk of his books from Jay Beard, another uneducated man who has simply forked over books he has come across in bulk. That Jay Beard has encountered nothing but Keats and Faulkner in his travels as a fisherman defies credibility, so we can presume Sydney must have bought or been given at least a few battered old copies of Shogun or an Ian Flemming novel. Did he just read them once, find the reading “airtight” and use them as firestarter the following winter? Well done Sydney, for tapping into the collective bias of the Ivory Towers without ever having stepped foot in one!

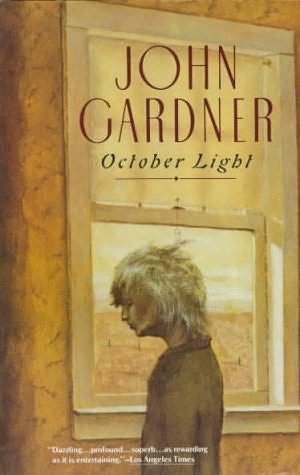

As an alternative to Sydney Henderson’s intuitive grasp of the Western Canon, I’d like to offer the example of John Gardner’s October Light. In this novel, an old man locks his sister in a bedroom where she has no company except for a cheap dime novel she finds discarded in a corner. She reads it to pass the time, knowing it is “trash” because her educated ex-husband had a keen sense of what a “good book” was. Nevertheless, she finds herself finding meaning in every corner of the book, and we as readers are given the same opportunity by the chapters-long excerpts Gardner shows us. The layers of the book are not so much peeled back as they are lain down by a reader who doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they aren’t supposed to bother.

As an alternative to Sydney Henderson’s intuitive grasp of the Western Canon, I’d like to offer the example of John Gardner’s October Light. In this novel, an old man locks his sister in a bedroom where she has no company except for a cheap dime novel she finds discarded in a corner. She reads it to pass the time, knowing it is “trash” because her educated ex-husband had a keen sense of what a “good book” was. Nevertheless, she finds herself finding meaning in every corner of the book, and we as readers are given the same opportunity by the chapters-long excerpts Gardner shows us. The layers of the book are not so much peeled back as they are lain down by a reader who doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they aren’t supposed to bother.

What Gardner is pointing out is that the depth of a novel has almost as much to do with the reader as with the writer – something Manguel knows and repeats in his book. So why, then, does Richards depict Sydney Henderson’s literacy in such bourgeois terms?

Manguel’s aside and Richards’ pretensions with Sydney both make me want to engage in a social experiment. Readers tend to read within a context assigned to themselves from without. Students read books critically because they know they are supposed to. Then they read their beach-books without a thought in their heads because, again, that’s what they are “for”. Even pedestrian readers will get out their pens if Oprah tells them this is a “book club” book and not just ANY old book. What happens, then, if we package Kafka’s The Castle in a glossy mass market edition with a Steven King-esque spooky cover? Or if the course work for your graduate class involved a lot of Clive Cussler in sober, Vintage trade paperback editions? Manguel asks this question early on in his book, when he admits to reading a text according to what he “…thought a book was supposed to be.” Kafka might be a deeper text, but is it self-evidently so, or are many of those 15,000 works of criticism prompted by the reader’s pretensions?

I’m going to read some “trashy” books this year in Canadian Literature, partly, I think, to spite Sydney Henderson. Also to give my powers of interpretation as a reader a trial run – after all, Edible Woman really has been done, hasn’t it? I don’t want to allow a community, however educated, to dictate to me what is going to be deep and what isn’t; what will make me a better human and what won’t. Especially – and this is a rant for another day – with a certain attitude in literary circles that a book isn’t good if it doesn’t make you want to move to Alaska and hang yourself. Despite it being Manguel who has got my pique up, he has also given me permission to assert myself more power over the text as its reader. I’ll take that, thanks, and meander down whatever paths my literary explorations offer me.

I hope it will be an interesting year!

March 15, 2009

Reading Canada, 2009

My goal this year is to exclusively read books by Canadian authors. Sound edifying? You might be interested in participating in John Mutford’s The Canadian Book Challenge 3 over at The Book Mine Set. For my part, I have read so far:

The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill

Outlander by Gil Adamson

Fruit by Brian Francis

The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant by Michel Tremblay

Mercy Among the Children by David Adams Richards

A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel

Robertson Davies: A Portrait in Mosaic by Val Ross

Widdershins by Charles de Lint

Roughing it In the Bush by Susanna Moodie

Nil: A World Beyond Belief by James Turner

Drawing on Type by Frank Newfeld

Therese and Pierrette and the Little Hanging Angel by Michel Tremblay

The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood

Hello I’m Special by Hal Niedzviecki

Hanging of Angélique by Afua Cooper

Hunter’s Oath by Michelle West

Airborn by Kenneth Oppel

Nikolski by Nicolas Dickner