August 26, 2009

Not Dead Yet

Despite weeks of silence, I am still alive, kicking and book-ing. “Rush season” has arrived at my book shop (which deals in a lot of course books for Universities) and only rarely am I allowed to be untethered from the receiving area. I will be free-range again come mid-September.

In the meantime, the Toronto Centre for the Book has just announced their 2009-2010 lecture series. Although they are now the official “lecture series of the graduate Book History and Print Culture Program in collaboration with the undergraduate Book and Media Studies Program”, the series is in no way restricted to students and academics. Attendees of all kinds are welcome. I’ve listed the lectures on the Events Page, but I encourage you to mark them down on your very own calendar.

August 4, 2009

Dumpster Diving at the Kelly Library

One of my favourite book-finding spots in the city is the Kelly Library in St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. Every week they stock a table in the cafe with books withdrawn from their stacks, and every week the entire table is replaced with a new batch of books. The books seem to represent particular sections of the library: one week might be American Cinema, the next week the French Revolution. Every book on the table is 50 cents, to be deposited into a little wooden box.

Visiting the Kelly Cafe is one of my weekly rituals. I don’t often find something to buy, but when I do it is usually something totally unique and impossible to have found any other way. I exercise uncommon discretion – I bike there and can’t cart a huge batch of books home, and anyway I want to leave some pickings for others.

I have lately been studying the ins and outs of German typography – blackletter fonts, Fraktur and the like – and by coincidence, last week’s theme at the Kelly Cafe seemed to be early-to-mid nineteenth century devotional and theological books in German. My typefaces were in full display here over about a hundred year period. But for whatever reason I didn’t buy any. I hesitated, wondered if I really needed them, hummed about the subject matter.

By the weekend I totally regretted my decision. Honestly, for 50 cents surely I should justify a few books to practice transcribing and identifying the texts! I tried to go back on Saturday only to find them closed, I tried phoning on Monday to find same. This morning I ran down there first thing in the morning to try to intercept my books before they vanished to wherever they go when they are replaced by the next week’s offerings. They had indeed been replaced (luckily, this week’s batch included some nineteenth century German philosophy, so I picked up a few books there).

I asked the librarians what becomes of the books once they are replaced. They are, I was told, recycled. In a meek voice I pushed further… had… the recycling been disposed of? Luckily no, it had not. Could I look through it? Why yes, I was quite welcome!

So a nice librarian took me down into the bowels of the library to root through their massive recycling bins. They were packed full of books – good books, interesting books! – and luckily, included my early ninteenth century German pickings. I scavenged what I could. I joked to the librarian, “I bet this must happen a lot – mad bibliophiles wanting to root through your garbage?” “No,” I was told. “You are the first.”

Alright, honestly. I can’t be the only girl in Toronto willing to sort through a library’s recycling in order to get at a useful (and free) book. But then, nobody took them when they were 50 cents and on offer in the cafe either. What is this?! Are ex-libris books really so maligned? These books are in excellent condition. Many are leather-bound. Some are old, many are out of print, lots are hard to come by any other way. Readers and academics will find treasures there.

I can only conclude that people must just be unaware of this treasure-trove. Hence this post today. Looking for cheap, good, interesting and unexpected books? Might I recommend the Kelly Cafe? You should check it out, weekly even! And buy things when you see them, because otherwise you might need to go dumpster-diving to get at them the following week in a fit of regret.

July 27, 2009

Visiting from the Land of Books

My maternity vacation is over and I have been back to work at the book room for two weeks now.

I have to confess that I have been cheating on my all-Canadian reading diet. One of the great hazards of working in a book store is of being distracted from the task at hand by any number of new, wonderful and enticing books sitting on the shelf. So while I do have Therese and Paulette sitting on the shelf behind me, 60 pages read, I haven’t been very faithful to it. I keep passing little curiosities, flipping them open and thinking, “well, it is only 150 pages. I can read this before lunch and then go back to something else.”

Most avid readers will tell you that they read four or five books at a time. Me, I try to focus on one. If I don’t apply some discipline then I will play favourites, tending to ignore the harder books I’ve undertaken. But then, a consequence probably of the fact that the harder or more boring books can sometimes take me months to get through, I don’t read as much as some people do. I certainly don’t read as much as I’d like to. In a good year I will read 40-50 books, in recent years (I blame knitting and child-rearing) I’ve barely read more than 20.

Two of the books I have read since being back at work, Books: A Memoir by Larry McMurtry and The Beats: A Graphic History by Harvey Pekar & co. feature autodidactic protagonists whose reading habits are described in the same terms as their hedonistic drug habits (well, maybe not McMurtry’s). They binge, they read obsessively, they escape for weeks, months into libraries and stacks. The great writer is the great reader, end of story.

Two of the books I have read since being back at work, Books: A Memoir by Larry McMurtry and The Beats: A Graphic History by Harvey Pekar & co. feature autodidactic protagonists whose reading habits are described in the same terms as their hedonistic drug habits (well, maybe not McMurtry’s). They binge, they read obsessively, they escape for weeks, months into libraries and stacks. The great writer is the great reader, end of story.

Having modest aspirations to writerhood myself I am therefore critical of my reading habits. Should I read more books? Better books? Am I better served by spending three months slogging through, say, Dostoevsky’s The Adolescent (my nemesis) or by reading back to back 6-8 shorter, more varied titles: some poetry maybe, essays, some more sparse novels? I go back and forth. And I cheat. Most ridiculously, I feel guilty about it.

Scattered and undisciplined as book store life makes me, however, it has its benefits. Customers, not unreasonably, always expect me to have read every book in the store. Is this any good? Have you read this? How does it compare to this? If I didn’t engage in little episodes of literary philandering I wouldn’t be able to bluff my way through these little interrogations quite so well. Customers who know me ask me my opinions without hesitation; they really do assume I’ve read it all. This isn’t as good as having read it all but it is flattering. The reading hasn’t reached full gestation and burst forth in a great literary creation yet but I am an awfully good bookseller. Maybe there’s something to be said about my destiny there.

So am I making excuses for dabbling and cheating and reading little bits all over the map? Probably. This is how I maintain my balance after all, but swinging back and forth between a disciplined assertion that good reading should hurt and a freer spirit of impromptu inspiration. In the end I get both done. Is it any wonder that our great writers (and readers) were all crazy or drug-addled? A person’s reading habits are a case-in-point expression of their neuroses. Does anyone read in a careful and measured way? Maybe that’s what casual readers do. Back at the book store torn between reads like a woman with too many lovers it occurs to me that even when I can’t squeeze many books in my reading is anything but casual. What to read entertains as much of my thinking as the read itself. Good lord. But I’m in good company, I’m learning.

As for blogging, by the way, it is and will be a more sporadic activity from here on in. Between work, reading, school, toddlers and living it has to exist between activities. My apologies if you prefer regiments and reliability! But I’m not gone, and continue to welcome your visits.

July 6, 2009

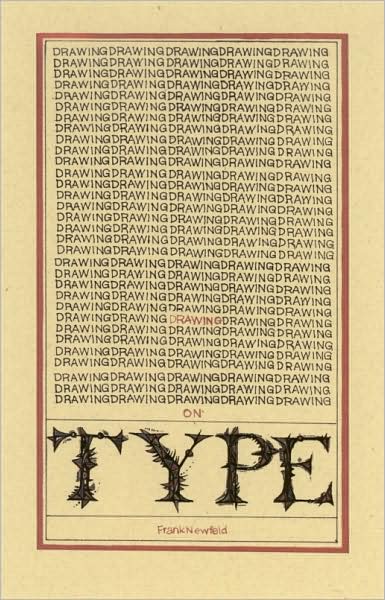

Review: Frank Newfeld’s Drawing on Type

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

Frank Newfeld is an illustrator, book designer, art director and all-around expert in the look, design and feel of a book. He was art director and subsequently a vice-president at McLelland & Steward under Jack McLelland as well as a co-founder of the Society of Typographic Designers of Canada (now the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada). Me, I best knew him as the illustrator of Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie & Garbage Delight, as well as being the guy who judged The Alcuin Society Awards for Excellence in Book Design in Canada. But what becomes evident over the course of his memoir is that he is decidedly not a writer.

I was a little torn about how to approach this review because of that fact. Newfeld has a lot to offer the reader in wisdom, anecdote and experience. That it hasn’t been rendered by a master storyteller doesn’t detract a lot from those elements. His delivery is simple and doesn’t pretend to be more of a stylist than he is, but nevertheless some parts of the book do suffer. The first half of the book is taken up with the first 25 years of his life, most of it spent in the military in Israel. Though he takes some first tentative steps towards his later career as an artist there, the vast majority of this part of the book is a fairly dull, two-dimensional rendering of places and names, the significance of which is not really given to the reader. Names are introduced three to a page, none of whom warrant any character-building. It reads a bit like an acceptance speech, where the aim is to recognize and thank all the influences in a life without giving the rest of the audience any hint of who these people were. This treatment of “characters” lasts for the rest of the book. Almost invariably if someone is identified with a full name it is to “name drop” them and give some laudatory praise, but no description. People who Newfeld is going to speak less well of are discretely identified only by first name, or title.

Even Newfeld himself fails to emerge as a fully-formed personality in the reader’s mind. That said, Newfeld describes the Canadian book trade in very different terms than I think we are used to hearing from those in the know. Unlike the love-in of glosses like Roy MacSkimming’s The Perilous Trade, Newfeld is critical of newer elements emerging in Canadian publishing in the 1970s-1980s. That Newfeld is of the generation prior to the Douglas Gibsons and Dennis Lees of the publishing world is quite evident. There is food for thought for those who would like to question why, if Canadian publishing underwent such a rebirth in the 70s, publishing today looks like a two-player racket pulping out more of the safe and predictable. Food for thought, but Newfeld almost sabotages his credibility with some of his recollections. In particular I found myself flinching through the long blow-by-blow of his difficulties with Dennis Lee and the publication of the children’s poetry Newfeld illustrated. Newfeld’s side of the story is, no doubt, just; but his manner of telling it comes off as petty. He makes nods to being fair and praises Lee when he should, but undermines that carefree tone with smug retellings of some pretty irrelevant incidents. A full-page quote of a bad review Lee garners from the Globe and Mail for one of his post-Newfeld books was totally unnecessary. That he continues to harp back to the same incidents for the next two chapters just reinforces the reader’s sense that Newfeld is being defensive.

Newfeld is, however, at his very best when he is describing a project or a process rather than a person or an event. This, I imagine, is the result of his being (by his account – and I have no reason to doubt him) an excellent teacher who ultimately wound up as head of the illustration program at Sheridan College. The art of design, typography and illustration comes brilliantly to life under his instruction, and his commentary on each discipline is insightful, measured and utterly authoritative. I was especially impressed with his very rational assessment of the use of modern technology in the book trade. I thoroughly expected him to express a curmudgeonly, out-of-date dislike for emerging technologies and found him instead quite open to innovation and experimentation.

This is ultimately what makes the book worth reading – the expertise and care that shine through when he talks about book design and book illustration. He is a genuine connoisseur of material book culture, one with more experience and laurels than many other people alive today. Even when you wonder if he’s being fair to some of the people and attitudes that he criticizes, you see exactly why, formally, he fights these fights. The man understands books in their entirety and is absolutely right when he says publishers are becoming far too focused on the author (and on the design side, the dust-jacket) to the exclusion of the other elements and people involved. This is a debate we don’t see enough of in book circles today. Newfeld is more than qualified to be the one to (continue to) lead the charge and I will, for my part, be taking him to heart in my future academic-and-blogging endeavors. Drawing on Type is a valuable text – and looks absolutely wonderful on my bookshelf.

July 2, 2009

The Scope of a Collection

I really do plan to be brief, this time. But some administration first: I won’t be holding a book collecting contest this month because I am out of town, nowhere near books in any kind of quantity. Our cottage is newly built and not yet filled to the rafters with summer books, though a new load comes in every week as my family wakes up to this opportunity to clear out some shelf space. In the meantime I am alone with the trees, rocks, lake, rain… and internet.

Enough about that. I wanted to speak for two seconds about the concept of defining the scope of one’s book collection. When I tell people I collect books they often reply with “me too, I have like two whole bookcases of books”. While this is “collecting” in a sense, it isn’t really what is meant when someone who considers themselves a serious collector says they collect. That, really, is hoarding, or owning. Collecting in a more formal sense means to define the bounds of a particular collection, deciding what is relevant and desirable and what isn’t, and seeking out those particular books. A collection can theoretically be completed some day, whereas “owning books” is something which goes on forever.

So defining the scope of your collection really is the single most important thing you will do. Simply put, this means deciding what is in and what is out. Cost, interest, practicality and availability might all factor. For some excellent advice on where to start and how to proceed with defining a collection, check out The Private Library. In the meantime, here is my current predicament.

I collect Alexandre Dumas (pere). The boundaries of my collection are intentionally foggy (I do like to surprises) but roughly speaking, I want to collect all of his oeuvre, one copy in French and one copy in English. I also love adaptations – his works repackaged and possibly reinterpreted for a specific audience. The Count of Monte Cristo as a graphic novel, say, or The Three Musketeers as a play. I do not collect “sequels” by third parties, or totally derived works (although I once found a website dedicated to someone’s collection who only collected sequels, unauthorized versions, derivations, etc. I wish I could find it now!).

Sometimes I make exceptions to the rule because it tickles my fancy to do so. I will buy any “and zombies” mashups that anyone chooses to do of Mr. Dumas’s works (a la Pride and Prejudice and Zombies). I refuse utterly to touch any of Disney’s many Musketeers interpretations – I am still offended that they call their little footsoldiers “Mouseketeers”. But what about this one?

Sometimes something is just ridiculous enough that I don’t know if I can resist. I mean, this baby even comes with a DVD. And the idea of Barbie as a character in a Dumas novel is so totally preposterous that I feel I might need it just to… I don’t know, counterbalance or juxtapose something. Somehow I doubt Barbie and her friends are carousing and scrapping, disciplining their servants and getting imprisoned. I wonder how Barbie feels about falling in love with fair Constance, then forgetting about her at the first flash of Milady’s milk-white bosom and ultimately sleeping with Kitty, the maid, in order to ferret out Milady’s nefarious plot. I wonder!

Sometimes something is just ridiculous enough that I don’t know if I can resist. I mean, this baby even comes with a DVD. And the idea of Barbie as a character in a Dumas novel is so totally preposterous that I feel I might need it just to… I don’t know, counterbalance or juxtapose something. Somehow I doubt Barbie and her friends are carousing and scrapping, disciplining their servants and getting imprisoned. I wonder how Barbie feels about falling in love with fair Constance, then forgetting about her at the first flash of Milady’s milk-white bosom and ultimately sleeping with Kitty, the maid, in order to ferret out Milady’s nefarious plot. I wonder!

Anyway, the moral of the story is, be disciplined but be creative. Sometimes the best collected materials are those ones you never thought you’d acquire. A hundred years from now when your collection is enshrined in a university somewhere (*coff*) you never know what some enterprising young grad student will do with the material. Personally, I see a thesis paper in here somewhere. Think outside the box!

June 29, 2009

Searching, Browsing, Print & the Internet

Last week’s SHARP conference gave me a lot to think about and more to post about, so let me apologise for the over-ambitious post-title you see above. I don’t mean to encompass the total sum of all current debates in book culture in one post. Don’t panic, this really is a lot more brief than it appears.

One of the more interesting/infuriating things about reading texts online, whether they be books, newspapers, blogs or articles is finding them. One of the great limiting agents of internet-based information is the search engine. It isn’t that search engines don’t find things, it is more that they find too much, often unrelated, information organized in a haphazard fashion. You, the user, then have to go back again and again searching for new things.

Consider my recent attempts to identify a strange little bug I found on my couch. Where once I would have turned to my Peterson Field Guide to the Insects of North America, instead I thought, “I’ll look it up online”. First I searched for “small black beetle Ontario”. Then “Identifying Ontario Beetles”. “Identify Ontario bugs”. “List of Ontario bugs”. “List of Ontario beetles”. “Is this a bedbug?” “Field Guide to Insects”. “Ontario Insects”. Etc.

Nothing I found was of any help at all. It isn’t that I now doubt that there is any information on insects on the internet. It’s just that I haven’t managed to hit on the exact tags that the unfound resource has used. Google does a valiant job of suggesting, refining, elaborating and extending your parameters, but this does not always result in a successful search. Furthermore, a search for “Ontario beetles” and “Identifying Ontario Insects” will yield entirely different results, despite their being very similar topics, probably both relevant to a person looking for information on the subject. But someone searching for one will not get the results of the other.

While at SHARP I had the priviledge of attending a paper given by Paul van Capelleveen of the National Library of the Netherlands entitled “Books will be Books”. For twenty very amusing minutes he showed us slide after slide of Wikipedia screenshots, all on entries relating to Book History in six different languages. The crux of his paper was not, as is usually the complaint with Wikipedia, that the information found was lacking or incorrect (though it was and it was), but that the information was totally different depending on what language you searched for the information in, and that there were few, if any, cross-references between the different language papers. So, someone searching for “Book History” in English will yield the title of a Journal and a redirect to the History of the Book article, a strange and meandering piece covering 9,000 years of history in about 1,000 words. The French entry, meanwhile, contains some articles translated from the English (or vise versa; I see the English entry refers to early printed books as “incunables” rather than “incunabula” – likely a literal translation from the French entry) while other sections are left out entirely, or relaced by different subheadings and articles. Meanwhile a search for “History of Writing”, “Old books” and “History of Literature” will yield whole new articles, not all of which are cross-referenced.

While van Capelleveen’s language distinction is interesting, I think this is just one more thing that highlights the problem with digital information retrieval. I have the same issues when I use The Toronto Star online, or Amazon.com. If I don’t know what I am looking for, I won’t always find what’s on offer. What they call “browsing” is just another form of searching, one where they allow that you might not know the exact title, but you still otherwise know what you want.

People tell me that computers now have that ability to link information in a more relational way, the way a librarian might. So, when you go to the library to look up book on Ontario bugs, you go to the Entomology subject and you find everything on bugs, from Field Guides to biology texts, whether they are titled A Field Guide to Insects or Creepy Crawley. And, similar subjects are nearby in case you have a slightly tangental issue. Newspapers work similarly; if I want to read about “Sports” I go to the Sports section and it’s all there, whether I know what team, game or athelete I am looking for or not. Do search engines help me thus yet?

Someone help me out here, because I haven’t figured it out yet. And it doesn’t look like the users of Wikipedia have either, as Paul van Capelleveen’s research shows so far. If all information really is going digital, this is top of my laundry list of requests. I need the pathing of a human guide, a librarian, an editor. Our language(s) haven’t standardized terminology yet, and probably never will. Do we all need advanced degrees in search parameters? I wonder.

June 24, 2009

A Wednesday Tidbit

I am at the SHARP 2009 conference (“Tradition & Innovation: The State of the Book”) all week and so don’t have time to make normal posts, so I leave you with this totally amazing website.

Sketches and paintings of favourite literary creators or characters by comic book artists. Above: Gene Ha interprets Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. But every piece is amazing – click on the image to check it out!

June 22, 2009

Interpreting “Archive”

I try pretty hard not to pooh-pooh the New Media, to keep an open mind about The Fate Of The Book and Literacy These Days as all of bookdom gnaws at their fingernails and tears at their hair over changes to print culture. But sometimes a news story comes up that really sets my nerves on edge.

The Library and Archives Canada has put a moratorium on buying paper documents and books for its collection. They cite the cost of buying printed materials, as well as some notion that digital materials might somehow be a more “efficient” expenditure of funds. Annoyingly, though this isn’t what I want to talk about, this freeze on spending includes the buying of antiquarian books.

What troubles me about this move is that I question the value of an “archive” which is entirely digital. I understand buying digital books for personal use – they are a cheaper and easier way to enjoy a casual reading experience, the kind where you don’t think back to the book after you’re done with it. I understand, even, keeping digital texts for a research library or institutional library – they are easy to search, can be used by multiple users simultaneously and are pretty accessible.

But I don’t grasp how archiving a text digitally serves the aim of an archive. From Library and Archives’ own website, “Library and Archives Canada collects and preserves Canada’s documentary heritage…” (emphasis mine). From Wikipedia, “In general, archives consist of records which have been selected for permanent or long-term preservation…” Other archives will state the same mandate. You will see words like “heritage”, “preservation”, “primary sources” and “unique” pop up regularly. Making records accessible is great, but is really the purview of the library: the task of an archive is to keep those records safe over a long period of time. It is a form of cultural protection.

The protection of records is an ongoing archival problem. Books deteriorate, are stolen, burnt or damaged. Languages change and are sometimes lost. Technologies upgrade and sometimes leave behind old, incompatable records. Nevertheless archivists do what they can to repair, copy and upgrade their charges in order to see that they survive to greet the next generation. We have come to a point where we take digital storage processes for granted, as if all of civilization has been building up to this technology one logical step after another. But it seems to me that instead it is one of the more precarious archival tools we’ve ever known.

To read a digital book, you need a program that can decode it. You need hardware that can read it. You need a device to run that program, and some means of displaying the results. You need a power source to fuel all of the above and then you need to start the sticky business of dealing with the text. Digital media is like taking a book, locking it in ten kinds of lock-boxes with different locks, disguising the whole thing as a rock and then burying it. You and I might, today, know where to find that rock, we can tell that it isn’t a rock, but rather a piece of technology, and then we have the complicated tools required to unlock all the boxes. But will we in a hundred years? Five hundred years? Two thousand years?

We have become very confident that our society today is the pinnacle of all former societies and, somehow, proof against all the pitfalls of other precariously balanced societies. We think we’re fail-proof. Information abundance has certainly perpetuated that belief; we think that if our political, social and communicative networks start to fail, that’s okay, because we’ve got so much junk around us to remind us who we are.

But this really is an illusion. Technologically sound and literate societies have come before us and have gone, and from their ruins we’ve managed to pick out bits and pieces of cultural ephemera and from that, we’ve painted pictures of who they were. Rock paintings, scrolls, disks, books give us evidence. We’ve preserved some of their wisdom and learning this way. Now can you imagine if, at the sacking of Alexandria, rather than being able to run off with what scrolls they could salvage, the librarians were stuck facing a server bank? What would they take? What would they save?

Now archiving isn’t just a safeguard against societal collapse and apocalypse, obviously. But it is concerned with permanence. The day of a blackout, or an electrical surge, a fire or an alien magnet or sun flare, is that digital technology available? Can it even be said to exist anymore? And what if future politicos cut the budget of the Archives, and render them incapable of the technology upgrades they need to continue accessing the technology? Is that it, the end? Nothing even to sell off in an auction?

Information integrity has been recently protected with redundance. Big companies have server space all over the world, spreading themselves out geographically in order to minimize loss due to environmental disaster or political upheaval (say). So, perhaps, Library and Archives intends to keep their archive (archives?) in multiple places in order to ensure that our cultural heritage isn’t nuked when a server reaches the end of its life. After all, this is one of the big benefits of digital technology: its quick and easy multiplication.

But then, what is the archive? The “original” document? Do they own it, or simply display it? Is the “copy” on Server Paris the same as the copy on Server Ottawa? Are all the copies safe from change? Who retains the record of what the document “should” look like, in case of deterioration, information loss, virus or vandalism? Where is the authority of the archive?

This barely scratches the tip of my anxiety iceberg, let me tell you. And how will this even save them money – are people suddenly giving etexts away for free? Did I miss the information liberation?

Nothing about “buying” a digital “copy” in order to preserve it sounds like a good idea to me. In fact, it’s a lot like buying nothing at all. Like this bridge here I have to sell you. I tell you if you wanted the real thing, it would cost you. But I can sell you a virtual one, cheap!

June 18, 2009

Now That’s Customer Service…

.jpg) During CBC’s Canada Reads broadcasts earlier this year I could be found all over the internet championing what I thought was not just the best book on the list, but one of the very best Canadian books I have ever read, The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant by Michel Tremblay. I was totally devastated when it was voted off the program, but I consoled myself with the knowledge that Michel Tremblay is a rather prolific author and I would have a lot more of his work to read.

During CBC’s Canada Reads broadcasts earlier this year I could be found all over the internet championing what I thought was not just the best book on the list, but one of the very best Canadian books I have ever read, The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant by Michel Tremblay. I was totally devastated when it was voted off the program, but I consoled myself with the knowledge that Michel Tremblay is a rather prolific author and I would have a lot more of his work to read.

In particular I was pleased to see that Talonbooks, the publisher, was offering a Canada Reads special – all six books of the Chronicles of the Plateau Mont-Royal in one handy package for a mere $75. I went down to my local bookstore (also, my place of work) to order it immediately. That was back in February.

I can’t report on exactly what happened after that, but it seemed that Talonbooks’ distributor, Raincoast, was having trouble locating the exact package deal I wanted. Phone calls were exchanged and databases were consulted, and we were assured my order was in progress. Time passed. More time passed. A lot of time passed.

I got the call, finally, a couple of weeks ago. My books were in! I hurried in to the store for my little darlings (paying $45 for the set – I work as a bookseller strictly for the discounts. I am paid in product, I’m afraid.) I only got around to opening the package today. I think, now, I understand what took so long. The package appears to have been lovingly assembled by hand by some industrious employee. A band cut from a 8 x 11 sheet of printer paper secures the books with some help from a bit of scotch tape. The cellophane wrapping is – I am fairly sure – Saran Wrap, also secured with scotch tape, liberally applied. The six books are pulled from the shelf in various states of shelf wear, some having been there for some time.

But I am thrilled none the less. I suspect that with Fat Woman‘s early exit from the challenge Talon gave up hope of having a great bestseller on their hands and withdrew the special. I’m sure they were surprised to get my order but, as good and honest bookpeople, fulfilled it anyway on a to-order basis. Somehow I like it better this way – I am left with the distinct impression of having been personally served.