April 1, 2011

The Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book: Digital Reviewing

Last night I attended the 17th annual Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book for the Friends of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The lecturer this year was the very prolific and always amazing Prof. Linda Hutcheon speaking on, to my delight, “Book reviewing for a New Age”. Well well!

Though Prof. Hutcheon is an academic and the Thomas Fisher is an institution within the University of Toronto, the Gryphon lecture is intended for a “layman” audience of supporters and friends. Unlike so many talks I’ve attended on book reviewing and the internet, the audience here was entirely devoid of persons employed by the publishing industry. These were readers, heavy ones, and especially, readers of print book reviews. So understandably, much of Hutcheon’s talk was aimed at making a case for digital forms of book reviews, and what they offer to readers.

In this regard, she was not tremendously successful. She began with outlining the decline of the print review, giving us a good history of which papers have scrapped their Books sections and why. The reasons given by the papers and by Hutcheon were all economic: it is no longer, apparently, worth it to a publisher to buy advertising at the same rates and quantities in print. The blame for that has been placed on the internet, probably rightly. The same advertising budget now has to include websites like Amazon.com, the lit blogs and the review copies given out through the thousands of social media channels.

The decline of print reviews has been matched by a much larger increase, however, in digital reviews. All signs point to an overall increase, rather than decrease, in engagement with books. Hutcheon explored at length the “economic, political and ethical” implications of this new divide.

I’ll leap ahead to the end in order to justify my opinion that she ultimately failed to make her case, however: no matter how many good points she made about the value of a more democratic engagement with books, or about increased readerships, the discussion never came full circle to re-include the print reviews. Ideally, she argued, print would broadcast the paid reviewer’s specialty: reviews with a “broader cultural scope”; expansive, reflective articles from persons who (ideally) are more professional and accountable than the customer-reviewer of the internet. Which sounds like a brilliant idea, but it doesn’t explain how this is going to be paid for. If publishers haven’t the advertising budgets to maintain Books sections in newspapers across the Western world, I don’t think it matters whether they contain snappy, puffy reviews or expansive, global-scope ones. Who’s paying for it? The internet has split the same dollar, and I don’t see either new money being added to the pile, or the internet losing it’s advertising appeal.

In any case, Prof. Hutcheon made some lovely and eloquent observations about the literary bloggosphere that addressed our weaknesses and highlighted our strengths. Though the most-often cited advantage of internet reviews is the “democratization” of the process – now anyone, anywhere can (and does) have a platform to let their views be known and the “tastemakers” or “gatekeepers” are losing their grip. But Hutcheon rightly points out that more noise doesn’t necessarily mean more dialogue – after all, can it be a dialogue if nobody is listening? Can critics have the same effect on our “cultural consciousness” if the discussion isn’t being broadcast (vs narrowcast) to a large audience? This is certainly a fair critique of the lit blog formula. Regardless of how measured, professional and well-spoken a blogging critic is, if he or she doesn’t have the same impact on the public sphere that the Globe and Mail, New York Review of Books or Times Literary Supplement has, the role of the critic in society is being diminished.

There are many advantages to the fragmented online review scene. It allows readers to seek out and connect with reviewers who share their tastes. Meta-tools like “liking” reviews on amazon.com do provide a way (however flawed) to distill some of the noise into helpful information. The customer-reviewer is an excellent person to consult when your question is “do I want to buy this” rather than “what does this mean” or “how does this fit into a greater cultural context?”

That customer-reviewers are a wonderful marketing tool is pretty inarguable. But are they anything else? A blogger isn’t as much a taste-maker as a taste-matcher; after all the reader can always go to another reviewer if they start to sense that her tastes are diverging from the reviewer’s. Hutcheon advances the suggestion that online reviewers are “cultural subjects” (after Pierre Bourdieu’s “Political Subjects”), meaning that even if they might not be the focus of a cultural turn or shift, they can at least be the subject of the discourse on culture – and I would take this to mean that the bloggosphere as a whole can be spoken of (“the blogs are saying…”) rather than specific blogs. This certainly has an egalitarian feel to it – we the masses making cultural decisions rather than individuals in powerful (paid) positions. Hutcheon suggests bloggers and reviewers are motivated by the reputation economy and by, of course, love of the subject. So perhaps as cultural subjects our impact is freer from the politics of power.

Except, I have to interject, I think that view of the bloggosphere as a rabble of altruistic amateurs happy to contribute freely to the dialogue is at least a little naive. The CanLit blogging scene, for example, is definitely blurring the professional/amateur line. Many of my favourite lit blogs are written by freelance print reviewers, and those that aren’t are written by people who, for the most part, have ambitions of becoming part of the paid “real critic” circle. Their blogs are, in this respect, proving grounds and elaborate CVs for budding writers and journalists who would be thrilled to death to be the next William Hazlit or Cyril Connolly. It seems difficult to escape the fact that the same people who are blogging are the people who are reviewing for the Quill & Quire, the Globe and Mail, writing for the Walrus, Canadian Notes and Queries, and the National Post, and publishing books destined to be reviewed by the same. It’s a small world out there. These are “customer-reviewers” to an extent, but it’s also becoming and increasingly legitimate in-road to becoming a professional critic. Even for those who have not made that leap to legitimacy yet, their contributions have to be read as something coming from someone who does consider themselves professional, even if no money is changing hands – yet.

In any case, the audience of Prof. Hutcheon’s talk seemed interested but unmoved by her arguments for the cultural importance of lit blogs and customer-reviewers. The average age of the audience-member was probably 65 years old, and these are, don’t forget, a self-selected group of people who choose to donate money to a rare-book library. The question period certainly was dominated by incredulity and derision at the state of the print reviews. Still, it’s good to know these issues are reaching even these, the least-receptive ears. The dialogue is spilling out into a wider audience, and it will be interesting to see how the discourse develops as the institution of reviewing continues to evolve.

March 27, 2011

“New and Improved” Dennis Lee!

Garbage Delight, 2002.

The poems of Dennis Lee are heavily favoured in our house, and so I was pleased to find a new volume called Garbage Delight: Another Helping, illustrated by Maryann Kovalski, during our last visit to the Toronto Public Library. It didn’t take long for us to realize that this wasn’t, as we’d thought, a sequel to the original 1977 Garbage Delight. Instead it’s an abbreviated version of the original book plus “some delicious new verses”, completely re-illustrated by a new artist.

I don’t think I’m just being nostalgic when I say I find this disturbing. As anyone with young children will tell you, the reading experience provided by a picture book is different experience than that provided by a chapter book, or a story told out loud. The pictures inform the child’s imagination just as much as the words do. Their eye follows the words and images, whereas they might not glance at the book at all during a chapter book. When you think of a favourite picture book, you’re thinking as much about the pictures as the story. Would Goodnight Moon still be Goodnight Moon minus Clement Hurd? Or The Paper Bag Princess minus Michael Martchenko? You certainly wouldn’t demand that classics illustrated by the author – the works of Dr. Seuss, Shel Silverstein, or Eric Carle – be taken apart and put together differently. Why treat author/illustrator teams differently?

Garbage Delight, 1977.

I don’t mean to say the book wouldn’t have been good illustrated by a different artist, but it would have been a different book. What disturbs me is how blatantly a re-imagining like this puts primacy on the words. Garbage Delight was a huge critical and commercial success when it was first released. Something about it resonated with the audience. In having it re-illustrated by a new artist the publisher (or author, or whoever decided this was a good idea) is assuming the text alone was responsible for that reception, and that an equal (or better) reception can be expected with new pictures.

The book industry seems stacked with people who make this error in judgement. Look at the popular attitude towards graphic novels. But any savvy graphic novel reader will tell you the graphics and the novel can’t be separated. Jeff Smith’s Bone, Dave Sim’s Cerebus, David Mak’s Kabuki – even team-written works like Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell’s From Hell or Jillian & Mariko Tamaki’s Skim – are works to be taken whole.

Why would a picture book be any different? In this case, I fear the answer is to be found in the ego of the author. Dennis Lee’s issues with Frank Newfeld were well-aired by Newfeld in his 2008 autobiography Drawing on Type. At the time I read and reviewed Newfeld’s memoir, I felt his take-down of Lee was rather juvenile (and it still seems pretty petty), but it now also helps shed some light on why Lee, a living author, might have condoned all of these re-releases of his older material with newer, duller, safer illustrations. He really feels these are his books. Newfeld points out the difference in his philosophy of illustration and Lee’s:

“Dennis felt that the illustrator’s only function was to describe the poet’s invention – to translate it, exactly, into the visual realm. Whereas I argued that the role of the illustration…was to challenge the child to take the poet’s flight of fancy and use it as a spring-board for his/her own invention.”

Frankly, I’m on-side with Newfeld. Authors are, of course, free to pursue whatever result they want with their words, but a picture book is not just an adult book with some colourful bits stuck on to attract the eye of an illiterate child. After all, kids (and grown ups) continue to enjoy picture books long after they learn to read and no longer need the visual cue of the images. The pictures bring more to the whole than representation. They are an entirely different level of the story, or poem. If the author can provide these themselves, great. If an artist is brought in to illustrate, their interpretation uniquely interprets the words. They are partners in the enterprise.

The new Garbage Delight fell flat in our house because Maggie found the inexpressive little raccoons confusing – she kept asking why they were all “sad”. She has always preferred images of children to anthropomorphic animals – but maybe that’s just us. I feel a little annoyed that I was tricked into picking up a book we already own – you’d think I’d be more careful. But I have absolutely never encountered this phenomenon before, and was not watching for it. Why re-assign your text to a new illustrator when the original was so successful? It feel straight-up like an insult. Even if I wasn’t the intended recipient of that slap, it’s embarrassing to see it on the shelf. I really hope I won’t ever see it there again.

Pretty much exactly how I imagine the Lee/Newfeld relationship - from Garbage Delight, 1977.

March 23, 2011

So What Is the Bookseller For?

Last week I got all hysterical about the ebook market, so this week I thought I’d talk myself back to earth to some degree.

I am not, and will never be, an ebook convert, but as Joe Konrath and Barry Eisler point out in this rather widely circulated interview, some people will always prefer the paper product and that’s okay: there ought to be a niche market for that. And there will, no doubt. After all, even within the paper book market there’s great a variety of technologies and processes in use. You have publishing giants producing perfect-bound paperbacks for cheap and disposable use (like Bantam), literary presses producing nice books for a global market (like Anansi), artisanal presses producing for the smaller trade market (like Gaspereau), and private craft presses who produce books using every technology ever known to man, from hand-crafted papers to letterpresses to calligraphy (like the Aliquando Press). The existence of Bantam hasn’t made a scrap of difference to Aliquando, even if they offer more books at a fraction of the cost. It’s a different market.

But to say that books of both kinds can live happily side by side is not to say that all will be well in the world of a book-lover, and it certainly means not all will be well for the bookseller. Our market is most likely going to evaporate. Bookstores who specialize in the first two types of books – mass market fiction and literary fiction – are likely to vanish first, as these are the texts which appeal most to “just readers” who don’t care as much about whether paper is involved or not. Booksellers who have a more narrow focus or specialty might fare better. A customer looking to contribute to a library of, say, books on architecture for reference in his firm is not going to be very well served by an eReader, especially not the current grey scale, small-screen ones. And there’s always the Collector.

This leaves the bookseller in a tight spot. You might be lucky enough to be a niche seller anyway. You might also, as some American independents are trying to do, diversify your business into ebooks. You might see if the big ebook providers are hiring buyers – after all, someone still needs to sift through publishing (or self-publishing)’s offerings and decide what to put on the front page of the website. (Though I even question the necessity of the buyer in the digital world – why not carry everything? Who needs discrimination? Space isn’t a factor anymore, and search engines hide from view everything that isn’t what you asked for anyway!) Would it be worth the rent to have a video-store-style bookshop, with bookcovers and tags in display, redeemable for ebooks at the cash register? Would the presence of a bookseller – someone to recommend and to consult – pay for the costs associated with meat-space?

I think it’s a fair assessment to say that tomorrow’s print-booksellers will become like today’s rare book sellers. They are out there, and some make a very good living. But they are as scarce as their product, and in big, expensive cities like Toronto often don’t feel they need to keep an actual open shop when a den and an internet connection does just as well.

I do wonder what I will be doing in ten years. My bookstore is niche, to some extent, so the realities of ebooks haven’t touched us yet. We have a customer base who are, often, buying books to build libraries rather than to read casually. We don’t deal with front-list fiction, except in so far as we feel like dabbling in it for our own sakes. Our best-selling publishers (university presses) produce books of a high physical caliber at a higher cost, which has never been a deterrent to sales. We’re doing pretty well these days. But can it last forever?

It has occurred to me that what I’m doing with all my print-book advocacy and paranoid blogging is promoting the product which I know my livelihood hangs on. I sell print books now, and I will still be selling them, with any luck, in ten years. The size of the market I am selling into, and thus my chance of staying in the business long-term, depends on how well I can sell you guys on the value of the printed book. I know, and I have always known, that ebooks are a great product for a certain kind of reading. But those books aren’t my product, nor my interest. I do something different, and would like to continue doing what I do.

So that’s my position, but I wonder about yours! Many of this blog’s readers are front-list fiction readers rather than collectors, and publishing industry employees too. A lot of you have eReaders and are reconciled to, if not happily accepting of, the ebook revolution. But you are also lovers and supporters of independent bookstores. I wonder, how do you see yourself reconciling those two stances? What is your ideal relationship with the independent bookseller when you have an eReader? What services to they provide you that you’d pay the premium for?

March 23, 2011

This is pretty much what I’ve been on about.

“So thequestion isn’t, “Will paper disappear?” Of course it won’t, but that’s not what matters. What matters is that paper is being marginalized. Did firearms eliminate the bow and arrow? No–some enthusiasts still hunt with a bow. Did the automobile eliminate the horse and buggy? No–I can still get a buggy ride around Central Park if I want… Paper won’t disappear, but that’s not the point. The point is, paper will become a niche while digital will become the norm.“

March 22, 2011

A Bookish Investment Opportunity – RPGs?!

Confession time! I love role playing. No, not in the naughty way, I mean sitting around a table with a bunch of my collaborators and pretending we’re other people for hours at a time. Dice may be thrown. Accents may be donned. We’ve generally moved beyond Dungeons & Dragons, but the love of collaborative storytelling remains.

What can I say? I’ve always been a nerd.

Table-top role players have always been closeted book collectors. It comes at them from two directions: first of all, they love props and visual representations of their imagined worlds, and the “leather-bound tome” is a favourite. The cover of role playing’s flagship text, the Player’s Handbook for Dungeons & Dragons 3rd Edition is mocked up with clasps and inlaid jewels, aping a decadent binding. Unsurprisingly, an actual leather-bound special edition followed the release of the game.

Table-top role players have always been closeted book collectors. It comes at them from two directions: first of all, they love props and visual representations of their imagined worlds, and the “leather-bound tome” is a favourite. The cover of role playing’s flagship text, the Player’s Handbook for Dungeons & Dragons 3rd Edition is mocked up with clasps and inlaid jewels, aping a decadent binding. Unsurprisingly, an actual leather-bound special edition followed the release of the game.

Secondly, role players have a tendency to be, shall we say, cautious about the condition of their books. We’re an obsessive lot. My husband won’t let anyone use his books as a hard surface to write on, for fear of indentations from the stylus marking his book. I know many people who keep two copies of their favourite manuals – one to be handled by their hands alone, and another for sharing. A friend of ours famously required interested parties to wash their hands before browsing his collection. And these are people who do not consider themselves book collectors.

So I shouldn’t have been surprised to find that there’s a very pricey market out there for used, out of print and rare role playing books. Considering most potential buyers are actually buying these books for use, not investment or collection, this is a bit stunning. The market exists almost exclusively on eBay, as book dealers don’t seem to have caught on. It’s an independent rare book market.

I discovered the market the hard way – trying to buy a book. The 7th Sea Player’s Guide has only been out of print since let’s say about 2005, and you’d think everyone who wanted to play then would have a copy already. Alas, mine was lost due to my very liberal book-loaning policies, and I needed a replacement. I got a deal – I found a replacement copy for a mere $80. The going rate is closer to $90-100. Not bad for a book that was $30 only six years ago.

I discovered the market the hard way – trying to buy a book. The 7th Sea Player’s Guide has only been out of print since let’s say about 2005, and you’d think everyone who wanted to play then would have a copy already. Alas, mine was lost due to my very liberal book-loaning policies, and I needed a replacement. I got a deal – I found a replacement copy for a mere $80. The going rate is closer to $90-100. Not bad for a book that was $30 only six years ago.

This prompted me to look up the going rate for a book I already owned, the Game of Thrones Deluxe Limited Edition guide. This was a Christmas present to my husband years ago, one which didn’t arrive until nearly a year after that Christmas. Production problems plagued the publication and the company went out of business shortly after – or was it shortly before? – the game was actually released. They honoured their pre-orders, but nothing beyond the original printing of either the limited edition or the standard edition was ever printed. Now, given the popularity of the novels the game is based on, and the upcoming HBO TV series, copies of this book are going for $250-$600.

This prompted me to look up the going rate for a book I already owned, the Game of Thrones Deluxe Limited Edition guide. This was a Christmas present to my husband years ago, one which didn’t arrive until nearly a year after that Christmas. Production problems plagued the publication and the company went out of business shortly after – or was it shortly before? – the game was actually released. They honoured their pre-orders, but nothing beyond the original printing of either the limited edition or the standard edition was ever printed. Now, given the popularity of the novels the game is based on, and the upcoming HBO TV series, copies of this book are going for $250-$600.

Which brings me to my Once Upon a Time book. Once Upon a Time, a company called Last Unicorn Games was set to publish a role playing game based on Frank Herbert’s Dune universe. As many as 3,000 copies were printed by Last Unicorn to be released at GenCon, the big North American gaming convention. But shortly before the convention Last Unicorn was bought up by RPG giant Wizards of the Coast (who publish Dungeons and Dragons; and who are owned ultimately by toy-maker Hasbro). Rumours circulated that this meant a newer, even bigger version of the Dune game would be published under the WotC banner, but in reality nothing was ever heard from the game ever again. Those GenCon copies were the only ones to ever see the light of day. (There are also rumours that much of the original 3,000 copy print run was pulped.) Today’s price? Ha! That would assume you can actually buy it. If one is lucky enough to find one on eBay or Amazon, you will probably be paying $500-$600 for it. But don’t count on one.

Which brings me to my Once Upon a Time book. Once Upon a Time, a company called Last Unicorn Games was set to publish a role playing game based on Frank Herbert’s Dune universe. As many as 3,000 copies were printed by Last Unicorn to be released at GenCon, the big North American gaming convention. But shortly before the convention Last Unicorn was bought up by RPG giant Wizards of the Coast (who publish Dungeons and Dragons; and who are owned ultimately by toy-maker Hasbro). Rumours circulated that this meant a newer, even bigger version of the Dune game would be published under the WotC banner, but in reality nothing was ever heard from the game ever again. Those GenCon copies were the only ones to ever see the light of day. (There are also rumours that much of the original 3,000 copy print run was pulped.) Today’s price? Ha! That would assume you can actually buy it. If one is lucky enough to find one on eBay or Amazon, you will probably be paying $500-$600 for it. But don’t count on one.

It’s enough to make a girl hesitant to use her books in a game! Or to take up book scouting…

March 16, 2011

Panicked Ranting in eBooks

Everything is not just going to be okay. I don’t care what publishers, the Globe and Mail and Margaret Atwood have to say. Increasingly I am finding that the scope of the ebook debate is being narrowed and dominated by certain interested parts of the book chain. Sure, many things about the ebook are wonderful. And they aren’t imminently going to destroy any part of publishing, Canadian literature or culture. But it’s a precarious perch the ebook sits on, and none of the interested parties seem aware of, or willing to discuss, this fact.

Over the last couple of years I have had and expressed grave concerns about elements of a theoretical digital future, and though I sit and wait patiently for these issues to surface, we seem to be coming further and further away from them. It’s because these are Big Picture issues that seem to exceed the scope of any one publisher’s five-year plan, or an author’s concern over becoming published. So listen, let me be crystal-clear about my fears. Do feel free to direct me to the appropriate pat answer.

EBOOKS ARE A TOP DOWN PRODUCT. Cory Doctorow or Joey Comeau’s latest schemes to retain control over their own art, distribution and sales included, ebooks are a highly specialized commodity which do not exist but for the grace of large corporate entities. I can not write an ebook without the help of HP, Adobe and Microsoft, and you can’t read one without Sony, Kobo, Apple or Amazon. Whoever wrote that file, however you read it, you are depending on technology which probably won’t work in five years, let alone fifty or two hundred. Big companies made the bed you lie in and their future is your future. Do they represent your interests? This is of archival concern of course, but it’s more than that.

I am concerned about the current format wars. A number of players – Apple and Amazon chief among them – are attempting to monopolize the ebook market. Proprietary formats and a “leasing” model to their business plans mean that their products are not transferable and adaptable to infinitely new reading devices. Eventually they will either “win” – gain a large enough permanent market share that it’s worth it to publishers to continue producing multi-format ebooks – or “lose” – fail to get that market share, and give up the project. Those defunct and discarded formats represent loss of information.

Amazon scares the bajesus out of me, not because they’re the biggest competition to any bookseller at the moment, but because their business model looks unsustainable to me. Books, unlike many consumer products, aren’t as easy to force into a discount economy. For starters, it really matters to a reader whether their book was written in Canada or in China. So while maybe you can look the other way and buy cheap, slave-made rubber boots from Walmart because, you know, they were only $5.99; you aren’t going to read a book by some faceless cheap labourer just because it’s cheap. At the end of the day, you want the new Philip Roth book and that comes with certain costs. Roth is a big one – the man would like to get paid. Producing his book comes with more costs: editing, formatting, design, marketing, publicity. These aren’t assembly-line skills and believe me, if they could be easily outsourced to Indonesia, they would be. As it is publishers have cut back on all kinds of former publishing necessities like editing and fact-checking because they need to keep prices down.

So Amazon’s predatory insistence that the price of books has to come down has a floor. They will never go lower than a certain point. Where that point is is a huge battle ground right now, and it really doesn’t benefit Amazon at all. People who try to comply go out of business, and people who stand firm either go out of business or keep prices up. The author, who is ultimately the product you are looking to buy, just goes to the standing publisher who can give her the best deal.

I have news for you, bargain-hunter: when Amazon sells you a new book for 50% the cost of the same book from an independent, it’s because someone is losing money. They’re either trying to create a loss-leader, a hook, or they’re trying to artificially force other publishers to “compete” with that price. Nowadays, they’re trying to sell ebooks at a loss so they we can all jump on board the Kindle and they can either make money on the technology alone or they can win the format war. It’s a big friggin’ gamble. If they lose, they fold up. And guess where your ebooks go? You never owned them, friend. And if it doesn’t seem likely this is going to happen in the next five or ten years, wonder where Amazon will be in fifty years, after your lifetime of book buying.

Yes, that might not matter to the buyer. It has been pointed out that the types of ebooks sold tend to be transitory desires. The kind of book you might leave in a hotel room. If you lose the “library” to a technology upgrade or a corporate bankruptcy, maybe you don’t care. But I’m skeptical of this idea of the two-tiered book market. Why on earth would any corporate publisher continue to sell paper books when all their money comes from selling frontlist blockbusters in ebook format? Ideology? And to whom would they sell these paper books anyway? Bookstores are the real vulnerable partners in the book chain. We don’t make or sell ereaders and, as of today, in Canada, we can not sell ebooks. We can only sell paper books. If even as many as 20% of my customers switch to ebooks, I go out of business. Without meat-space bookstores selling dead-tree books, the market for real books gets more and more marginalized. So you might not care about your digital book collection, but will publishers continue to support the paper book “backups”? An even smaller market means the cost of the book goes up – again – which leads to even fewer buyers. Amazon may or may not consider it worth their while to deal in “premium” Real Books. Buyers may prefer digital books to the inevitable POD (print on demand) ones, which remain hideous.

Obviously we’re not there yet. Many, many people still prefer real books. But it drives me nuts when I listen to discussions between publishers and writers, for whom, frankly, the question of digital-or-not-digital is moot, since their product is the content, not the format. They seem to forget the roles of other parts of the book chain. Typical, for people whose vested interest in the product vanishes the minute it is sold. Where are texts without bookstores? Without a second-hand market? Without reliable archives? Under censorship? To people who can’t afford to upgrade hardware every 5 years? Does it matter to them? Not a whit. As long as the frontlist sells, somehow, to someone, through anyone.

Now I want to stipulate that I don’t feel my apocalyptic vision of the digital future is in any way inevitable. But I think it will be if we keep treating Amazon and the big book chains as the benevolent godhead of book distribution. Publishers do this, writers do this, and increasingly, customers do this. Doctorow and Comeau aren’t just desperate writers who can’t get publishers, they’re authors who glimpse the danger of a book future where the control of big companies isn’t questioned. They are also, unfortunately, dependent on Our Corporate Overlords to produce their product, but at least the first glimmerings of awareness are there. The digital future is going to be bleak unless we question the health of a market run by a few players.

We all know the possible solutions. We need to settle into an open-source ebook format which can be freely exchanged between platforms. We need to open the market up so that independent players can sell the same ebooks that the big chains can. We need to stop pushing for ever-lower prices on texts. Publishing and readership will remain healthy if and only if we consciously address the format’s weaknesses. Tell me exactly what is being done to make sure these texts last. To guard them against censorship. To allow small and large publishers equal access to readers. To manufacture, distribute, and dispose of the delicate and expensive ereader technology equitably. To protect all of our joint investments if, god forbid, some discounter’s insane scheme to control the industry doesn’t quite pan out.

Stay tuned for next week’s installment: What Purpose Do Booksellers Serve, Anyway. Maybe by then I’ll have rooted out some answers for you.

March 15, 2011

The Lazy Reader

I’m not going to lie to you – I’ve been reading a lot of junk lately. Call it comfort reading. I am engaged in re-reading the entire Dune Chronicles by Frank Herbert for, probably, the tenth time in my life (but the first time as an adult). In between escapes to Arrakis I’ve visited one young adult novel (Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie) and one romantic melodrama (The Two Dianas, credited to Alexandre Dumas but, upon reading, more likely written by a collaborator) – nothing heavy or challenging. And, truthfully, I will probably start reading Patrick Rothfuss’s “Kingkiller Chronicle” next, because it’s been a long time since I’ve read any serious fantasy and I’m kind of pining for it. That’s just how I roll.

While none of the books individually are especially shameful, taken as the sum total of what I’ve read this year (beyond Canada Reads), it’s a bit of a disgrace. I’ve said as much to my friends and co-workers, and a fair percentage of them have responded with some version of “So what? Read what you want to read! There’s no shame in that!” I selfishly appreciate that sentiment, but it’s hard for me to agree with it. Is that all that reading is to me – just a leisure activity? A quiet, dignified form of watching television? It isn’t as if my literacy is in question. Looking at words on a page a certain number of hours per day isn’t doing me any inherent good – in fact it’s ruining my eyesight quite steadily. I’m beyond needing the “practice” of any old words.

Leisure itself is an indulgence. Of course it’s lovely and we should all have some, but a life of pure leisure is decadence and there’s some Victorian part of me which feels honour-bound to strive for a little more out of my life. I’m not a doctor or a politician or a social worker. I don’t spend my many hours giving to my community and helping my fellow persons – I sell books and I spend 8 hours a day reading, or reading about reading. If all my reading is pure self-indulgence, I might as well say my entire life is spent goofing off. I need to dedicate my reading to something bigger or better than pure enjoyment.

Throughout history the value of different kinds of reading has been questioned. Until a hundred years ago, the reading of novels of any kind was considered an indulgence – today we read nothing but novels. The feeling that novel reading is frivolous certainly persists, however. The Guardian recently reported that male writers and reviewers dominate the big literary papers and in their defense, the TLS was quoted as saying “And while women are heavy readers, we know they are heavy readers of the kind of fiction that is not likely to be reviewed in the pages of the TLS.” Horrible as that sounds, my experience as a bookseller has been that he’s more or less right. The TLS reviews, primarily, non-fiction. They usually have one big fiction review and a page of little mini-reviews, but the bulk of the supplement is dedicated to forms other than the novel. In my experience, the primary readers of non-fiction are men. There’s an odd split here – the students we see at the store coming in to buy English course books are overwhelmingly female, but our “regular” customers who buy the rest of the store’s stock (primarily philosophy, cultural theory and politics) are overwhelmingly male.

This reflects a feeling that the serious intellectual spends his or her time reading non-fiction. It’s reflected in the pages of the TLS and the New York Review of Books. It’s reflected in the offerings from University Presses. And I am not going to mount a defense of novel-reading here. There’s no question that some novels have the power to expand the reader’s mind and bring important dialogues into the public sphere, and I don’t think anyone would argue otherwise. But much novel-reading is entertainment, even when at its most beautiful. Like other forms of art, the very best can change the world, but the bulk of it, while pretty, is mostly decoration. The overall themes, trends, and qualities of a literary culture reflect and inform society as a whole, but taken one book at a time, these are “just’ moments of indulgence.

I’ve always felt a book should be undertaken for a reason. To inform or to answer questions. To instruct. To introduce new cultures and stories. To sample the thinking of a different place and time. To challenge your intellect. Most books can fill a use, but to remain engaged by what you read, the reader has to take some responsibility for choosing books which continue to challenge and open new doors. Too much comfort reading and you’re accomplishing nothing with each new book – just spending time, albeit enjoyably.

I think of myself as being on a reader’s vacation. The kind where you visit some Westernized resort and do absolutely nothing of value until you run out of money and have to fly home. I’m lying on an metaphorical beach, unwinding and letting myself be pampered. It’s nice, but I wouldn’t want to make a habit of it. Eventually I have to come back to my real life and re-engage. If this blog has seemed slow, this is why: lazy reading only produces shallow thinking, and there’s little to report to an audience.

I think of myself as being on a reader’s vacation. The kind where you visit some Westernized resort and do absolutely nothing of value until you run out of money and have to fly home. I’m lying on an metaphorical beach, unwinding and letting myself be pampered. It’s nice, but I wouldn’t want to make a habit of it. Eventually I have to come back to my real life and re-engage. If this blog has seemed slow, this is why: lazy reading only produces shallow thinking, and there’s little to report to an audience.

Dune and Rothfuss aside, I think my vacation is coming to an end soon. I’m starting to feel guilty. I’ve picked up J. G. Farrell’s Siege of Krishnapur in a lovely NYRB edition for my next read – yes, still a novel, but hopefully one with more horizon-expanding capability. Time to get back to work! What the overall project is in my case I’m still not sure but my hope is eventually my brain will be filled with enough ideas that some kind of fully-formed result will just pop out of it. Hope you’re all reading well too!

March 10, 2011

Yay!

I came home last night to find a giant box-in-a-bag on my front porch. It was the first of three shipments from the Folio Society!

Inside was not only my four Fairy Books and a dictionary/thesaurus set, but quite a lot of bubble wrap, which was greatly appreciated by the young miss.

Now they live on the newly-named “Folio Shelf”, where they are getting cozy with some of my older Folio Society acquisitions. Except for the first, the Blue Fairy Book, which is our new bedtime reading.

March 8, 2011

Happy International Women’s Day!

Not too long ago we discovered (to my delight) that the small wiggly proto-baby in my belly is most likely a girl, my second. This makes my life easier on many accounts, but on one it opened an old wound. What do you name a girl?

I am a staunch believer in “names with meaning”. I don’t care a lot what a name sounds like, and I am outright offended at the practice of naming girls after pretty but inanimate objects (Ruby, Ivy, Lily, Yuki, etc.) or limp character traits (Grace, Hope, Harmony, Chastity, etc.) I like a name with strong historical and literary connections. I want to say I have named my daughter after a history of women she can be proud of.

Miss Margaret

My first daughter is named Margaret, after (mainly) Marguerite de Navarre & Marguerite de Valois. The former is most famously the author of The Heptameron, while the later’s life inspired both Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost and Dumas’ La Reine Margot. My favourite of her accomplishments was her managing to get her loveless marriage to Henri de Navarre dissolved, but maintaining her power and title of Queen. To say nothing of her impressive list of romantic conquests, the coup d’etat she orchestrated, and the many scandalous writings she left behind. Margarets, too, have an illustrious presence in Canadian literary circles, of course. When she was 3 months old I took her to the Trinity College bookfair, where a new acquaintance exclaimed, “Ah! Margaret! As in Drabble?” to which I replied, “No, as in Laurence!”

What to name her sister? Part of my problem is epitomized by this article published in the Guardian this morning, Where are all the daring women heroines? Strong, heroic women in literature are few and hard to come by. True, children’s literature is plush with them, but this route is somewhat infantilizing. Speculative fiction is debatably a source, but comes with its own set of problems. Much specfic isn’t very good for starters – I’m not naming my child after a two-bit chick in some forgettable contemporary novel. Many of the “heroines” are undermined by weaknesses that wouldn’t be found in their male counterparts, and in many cases male co-heroes hog all the best page-time. And I’ve a bit of a rule – no names that entered our vocabulary less than 50 years ago. Sorry, kids.

And what does it say, anyway, that the strong female heroine is a trope only of the land of make-believe? Is our history really that poor? Or is the modern, real world too gritty and unequal to even pretend that out there are strong, uncompromised women kicking ass and winning? I believe in the power of names, so I want a name associated with power. My husband and I find ourselves throwing around names like Sheherazade and Boudiccia. We’re mining Shakespeare – Beatrice, Rosalind, and Catharine have come up, but seem like stretches. After all, with the exception of the tamed-Catharine, none of these women are the central figures of their stories. Dear Josephine (of Little Women) is an option, though it happens that we know a number of young Jos already.

This shouldn’t be this hard! But the paucity is in the source material. Where are the heroines? Send me your strong, unvictimized, accomplished literary women; those who didn’t get murdered, kidnapped, tamed or commit suicide. On International Women’s Day, this feels like a mission.

March 3, 2011

Returns Season

It’s returns season at the bookstore. It comes for all bookstores: it means our year-end is coming and we need to get as much unsold stock out of the store as is reasonable. I know some big book chains who shall not be mentioned have had, in the past, a reputation for abusing returns privileges with distributors, but for us the right to return is a necessity of survival.

We stick to the rules – we never return more than 10% of our orders to the publishers – and I like to think it benefits everyone. We gain the flexibility to gamble on unknown publishers or authors without fear of getting “stuck” with the book. We can order quantities of books for university and high school courses that might otherwise be foolish (after all, when a prof tells you “I have a cap of 200 students” this sometimes means “… but only 44 signed up”, and nobody would ever tell us. Not to mention the sometimes enormous numbers of students who choose to buy their books elsewhere, use the library, or flat out not read the book. Anyone who thinks university business means guaranteed money is kidding themselves.)

We also have a private policy of not sending books back to certain distributors unless we really have to. We will keep lots of things well past the return deadline because we really ought to have it on the shelf (nevermind that something like Roland Barthes’ Mythologies might only sell once every three years – we should still have it.) We keep small Canadian independent publishers almost indefinitely because we feel bad sending the books back to them. But on the whole, we need to be able to send back a lot of the stock every year to balance the books, clear out some space and cut old losses.

This is a dangerous time of year for yours truly. I can’t send a book back that I’ve had my eye on all year. I have to “intercept” a lot of titles now as I feel it’s my last chance to get them before they go back. And then there’s the sale books – oh yes. Anything that’s past the returns deadline and considered no longer good for stock we cut to 50% or 75% off. You better believe I get first crack at those!

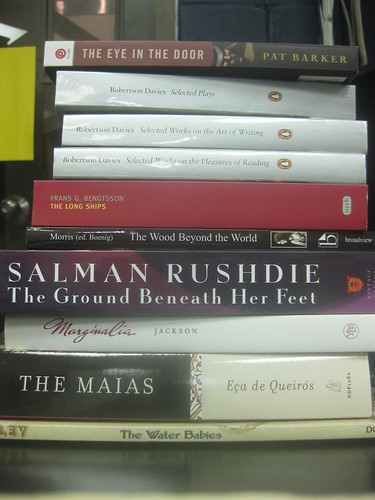

As of this morning, the damage looks like this:

And this is why I’ll never own a house…