May 17, 2011

On Elitism and Culture

I’m going to describe a phenomenon which I suspect reflects a deep social divide, like left vs right politics, or religion vs reason. There are those who think that literature, like every other art, is something everyone can produce with a little intelligence and hard work, and there are those who think great art is a talent; an unteachable flame of inspiration that only a lucky few can produce. It’s a divide recently exhibited by Elif Batuman and Mark McGurl in their exchange over the value of creative writing MFAs: Batuman feels MFA programs are pulping out legions of under-read hacks (to put hyperbolic words in her mouth – she’s much more even handed than I am), while McGurl feels “a more democratic culture is possible” and that the “workmanlike” literature produced by these programs benefits society in more diverse ways than simply, say, producing a great book.

I don’t think you have to think too hard to see how this same rhetoric is also cropping up in discussions of ebooks vs paper books, most recently evoked by Natalee Caple in this essay for the National Post. “Is this literature, you might ask? No, I do not argue that it is. Instead, it is something more radical. It is free thought; it is democracy.” says she. Ebooks (like MFA programs) have widened the field, and can give everyone a voice.

Putting aside the fact that ereaders, like MFA programs, aren’t actually especially accessible to genuinely disenfranchised people, I think the argument anyone can (or should) be a writer is misguided. Literacy is a beautiful thing and a true pillar of democracy. It lets everyone have access, in theory anyway, to the same ideas, the same education, the same public sphere. It lets everyone potentially in on the important, society-changing movements. The ability to decode texts is absolutely, unquestionably valuable to democracy. And then, for the most part, the right to say whatever you want in the public sphere is also a vital part of democratic life. Voices should not be silenced and marginalized: therein lies control and potential abuse. People should have the right to write.

But let’s be honest here: ebook publishing and MFA programs are not about freedom of expression. They are about producing a marketable product. You don’t enroll in an MFA program because you need to make charges about people in power or because you have a great new approach to irrigation you’d like to make available. There was nothing about the old publishing structure that was preventing marginalized or radical people from expressing their ideas. Plenty of old-school publishers were happy to put their money where your mouth is, publishing revolutionary tracts and out-of-the-way stories. To boot, they’d edit, develop and promote your idea, helping it find a bigger audience than you could have on your own. If your ideas are so out in left field that you can’t find a publisher, well, you could always self-publish them. Even without the money for a vanity publication, you could print your pamphlets at Kinkos.

But it’s easier with an ereader, you say! Is it now? I will tell you something from a bookseller’s perspective: we won’t carry self-published work that doesn’t have proper distribution, no matter how it was printed. Similarly, we’re happy to carry cheap little tracts – so long as they come through the usual channels. I don’t believe for one second that Amazon, Chapters or Apple are much more generous than we are. They will not sell your book if the content offends them. Even if you’re listed, there’s no guarantee of “spotlight” status. “Ranked” search engine results and hard-to-search-for designations like “adult” status can keep your book out of sight indefinitely. Its simply having been published using the right software doesn’t give you the right to be sold through their stores. It’s the same game in the end: whether or not you are read is not about being able to set words on page or screen.

I don’t believe ebooks make voices from the margins any better heard than, say, html documents did back in 1995. Or the photocopier did in 1959. The problem was still how to make people read marginal texts. Will it be easier to get a copy of a marginal ebook than it was to access a marginal webpage? Do MFA programs map a solid path from the classroom to the front table at Chapters? The answer to both questions is of course no.

What they do offer is, perhaps, a better model for getting paid if you are self published. In both cases, however, the path to money has nothing to do with democracy; if anything, it is undemocratic. An MFA program will teach you to write the way publishers want you to. They’ll help you develop a voice that sounds a lot like the big prize winners from the last ten years. Self-publishing an ebook, especially if you do it through (Amazon subsidiary) Lulu, will give you the right to be sold on Amazon.com, the Apple ebook store, or Chapters (unless of course they object to what you’ve written.) Both phenomena might help you get sold (and then presumably read) if and only if you play the game nicely and produce a product they think will sell. On Caple’s continuum between democracy and capitalism, this lands squarely at the capitalism end of the spectrum. MFA programs are a tool to get published and sold, and ebook platforms are a tool to get big chains to distribute your book to be sold.

Booksellers (small and large) might be the “hegemony”, but we’re better representative of readers’ tastes than McGurl or Caple give us credit for. We’re not part of a big machine standing in the way of fresh new thoughts and voices (well, Amazon might be). If a crummy book isn’t being read, it is not our fault. The myth that learning to write program fiction, self-publishing and selling on Amazon is going to bring the limelight to countless marginalized voices is just that: a myth. Readers don’t read at random, and don’t read indiscriminately. Simply showing up in Amazon’s vast database does not guarantee you any more readers than putting up a website or going out to trade shows or press fairs would. If anything, the increased self published noise out there is going to make it harder than ever to stand out in the crowd. You need the bookseller: you need a mechanism to sort through the noise. Booksellers read, Amazon’s search engine does not.

It should come as no surprise to anyone that I come down on Batuman’s side with regard to the creation of great literature too. Not everyone has a writer in them. No creative writing class or self-publishing tool is going to turn any literature student into Tolstoy. The reader has no responsibility, democratic or otherwise, to read mediocre literature. And lastly, democracy does not guarantee anyone the right to make a living doing anything they please. That there are tools available to help people make a buck by buying into an expensive system dictated top-down by corporations isn’t democratic. It’s a pyramid scheme. Nobody is making more money in this system except the people who were making money already. The rest of us are being sold snake oil.

Thanks to Kerry Clare (and her more even-handed approach) for getting me thinking about this this morning!

May 9, 2011

Eep.

Totally blew the budget at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Well, fine! Someone rather eloquently pointed out that ’tis better to buy than to hesitate when it comes to supporting emerging, local, or or self-published creators. This is an economic theory that sounds right to my ears. Should I ever create anything some day I’d certainly appreciate a tendency to buy rather than to hesitate, so let’s just say I’m paying it forward and move on.

What did I get?

Baba Yaga and the Wolf by Tin Can Forest (aka Marek Colek and Pat Shewchuk)

The Next Day by Paul Peterson, Jason Gilmore & John Porcellino

Lose #3 by Michael DeForge (Wish I’d grabbed his now-Doug Wright-winning Spotting Deer as well)

Cat Rackham Loses It! by Steve Wolfhard

Moving Pictures by Kathryn and Stuart Immonen

Entropy #1-6 by Aaron Costain

Catland Empire by Keith Jones

Bigfoot by Pascal Girard

Paying For It by Chester Brown

Sweet Tooth Vols. 1 & 2 by Jeff Lemire

Jeff Lemire Sketch Book by… yah.

Galaxion #2 by Tara Tallan

From Toronto to Tuscany by Kean Soo & um… Tory Woollcott? Forget; apologies.

Northwest Passage by Scott Chantler

Pang, The Wandering Shaolin Monk by Ben Costa

Along with the books and comics was an assortment of bookmarks (I am such a sucker for bookmarks), postcards, stickers, keychains and at least one pair of socks. And I wish I could say I got everything I wanted, but I did not. Time ran out, carrying capacity was reached, and some other logistical difficulties plagued us. I would have bought more prints but for the fact that my house is already full of unframed prints and posters that I can’t work out what to do with. IKEA frames never fit anything! My kingdom for a cheap and easy framing solution.

Needless to say, I had a blast. By the look of Twitter, so did everyone else! There’s no question that this festival is getting stronger as it goes forward, and I am so proud to have it in my own city!

May 6, 2011

Obligatory Pre-TCAF Post 2011

The Toronto Comic Arts Festival is one of those events that I budget my whole life around for an entire quarter. Which is funny, because if all you know of me is what you learn from this blog, you might not have me pegged as much of a comic geek: I tend to blog about book collecting, book-as-object issues, bookselling and Canadian literature. Comics, a huge subject on their own, I tend to pass over for other things.

The Toronto Comic Arts Festival is one of those events that I budget my whole life around for an entire quarter. Which is funny, because if all you know of me is what you learn from this blog, you might not have me pegged as much of a comic geek: I tend to blog about book collecting, book-as-object issues, bookselling and Canadian literature. Comics, a huge subject on their own, I tend to pass over for other things.

The truth is that I am a bit of an outsider when it comes to comics. I’m aesthetically barren and not especially hip, yet not nerdy enough for mainstream comic geekery. I encounter and consume graphic novels with a kind of layman’s how do they DO that??? awe. There’s no doubt that I love the finished product, but I have little to no insight into the techniques, styles, influences, communities and trends that come together to produce the work.

However, there are a few things I can say for sure. FACT: TCAF is one of the best, if not THE best, non-mainstream comic shows in North America. FACT: Toronto itself has produced a disproportionate number of incredibly influential comic artists and cartoonists, suggesting there’s something to the community here (or maybe just in the water) that’s creating a comic arts nursery. FACT: The Beguiling, the instigator and host of TCAF, is just about the best comic book store ever. FACT: The graphic novel is becoming an increasingly legitimized literary form and TCAF is probably the single best place to learn about and buy the best and brightest of the form.

Last year I posted 5 Things That Will Be Totally Amazing About TCAF 2010, and the year before I discussed The Toronto Comic Arts Festival and Why a Book Collector Should Care. This year I admit I have nothing to add to those points. But the importance of TCAF hasn’t lessened any, so consider this a simple reminder: Get out there! The launch party is tonight, and the Toronto Reference Library will be packed to the rafters with vendors, exhibitors and panelists Saturday and Sunday (May 7th & 8th). The show is free so there’s virtually no reason not to check it out. It’s even kid-friendly. Aside from being a colourful spectacle of the graphic and literary cutting-edge, there’s also a whole rooster of kid programming.

It has been a good spring for book festivals so far!

May 3, 2011

My Weekend in Grimsby

Can I just say, Grimsby is a beautiful little town! I’m jealous of anyplace that gets a proper green, flowered spring, and such a spring was certainly on display Saturday when we visited for the the 33rd Annual Wayzgoose. The atmosphere was warm, cheerful and tastefully tactile.

As a bonus, the Grimsby Public Art Gallery was also displaying The Nature of Words, a travelling exhibit of book-related art. I saw this show when it debuted in Toronto and wasn’t completely captivated by it. The artists represented were top-notch book artists in their various fields (binders, printers, paper makers and so on) but the focus of the exhibit was on words rather than the means of transmitting those words. The result was a lot of out-of-context prints, banners and fragments which failed (in my opinion) to show the best of what these accomplished book makers could do.

However, in Grimsby the artists and presses who participated in The Nature of Words had their booths in the gallery, and finally visitors could see the really stunning work in book form that they produce. These were among my favourite offerings of the show – Will Rueter’s Aliquando Press had nearly their entire catalogue on hand and I was totally taken by the lovely work Locks’ Press had on offer. Binder Don Taylor’s booth had some design bindings on hand as well as smaller pamphlets from his Pointyhead Press. If The Nature of Words had originally contained more of these press’s books and less “art”, I might have enjoyed it more the first time around!

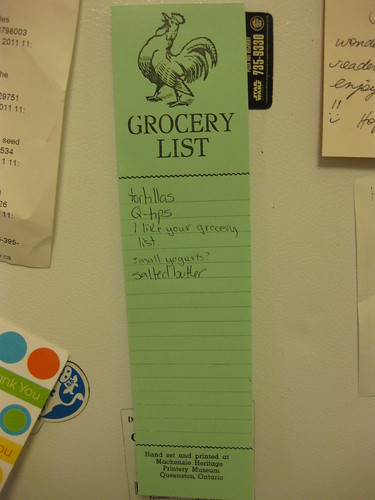

But not everybody – not even book arts followers – are as fixated on books themselves as I am, and the rest of the show featured as many if not more presses and artists who work outside of the codex form. There was a glut of cards, bookmarks, prints and posters, coasters and other paper-based curios. This makes for incredible shopping, regardless of your interest! It’s far too easy to spend $2-$10 at every single booth in the show buying some beautifully printed bit of ephemera or another. Which I did, I think. How could I not? My favourite ephemeral offering? Grocery lists from the Mackenzie Heritage Printery & Newspaper Museum:

But not everybody – not even book arts followers – are as fixated on books themselves as I am, and the rest of the show featured as many if not more presses and artists who work outside of the codex form. There was a glut of cards, bookmarks, prints and posters, coasters and other paper-based curios. This makes for incredible shopping, regardless of your interest! It’s far too easy to spend $2-$10 at every single booth in the show buying some beautifully printed bit of ephemera or another. Which I did, I think. How could I not? My favourite ephemeral offering? Grocery lists from the Mackenzie Heritage Printery & Newspaper Museum:

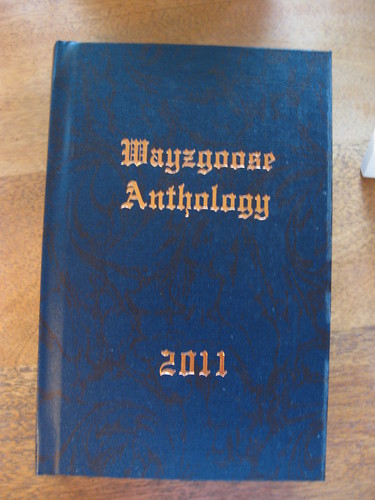

I wish I could say I restricted my buying to tiny and affordable curios, but I did not. I couldn’t leave without this year’s Wayzgoose Anthology. These books contain one signature (a folded sheet) from each of the exhibitors. The final product is a strange mish-mash of beautifully printed poems and essays, lithographs and woodcuts, fold-out maps, hand-coloured drawings, collages and handbills. I would estimate that 100-130 of these were printed and bound, the majority of which go to the exhibitors. I NEEDED TO HAVE ONE.

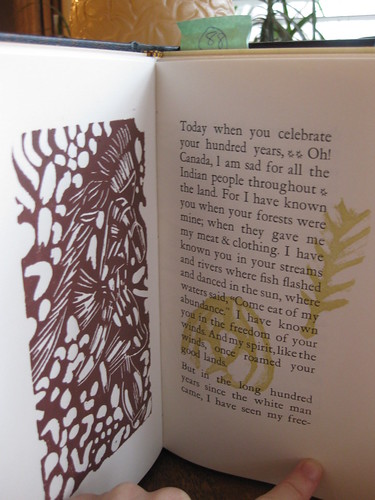

Some of my Wayzgoose pages...

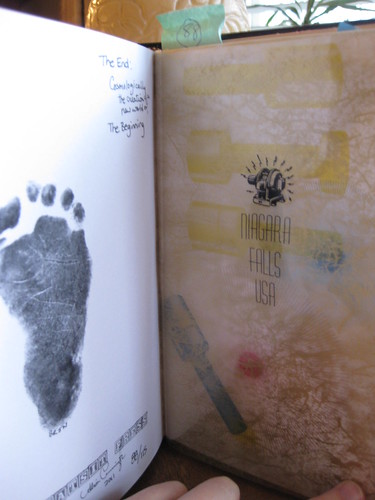

More Anthology pages...

April 25, 2011

Things to do this weekend: Wayzgoose!

I couldn’t possibly be more excited about this weekend, because for the first time in years I will be traveling outside of Toronto exclusively for a bookish event: the 33rd Annual Wayzgoose in Grimsby, Ontario.

I couldn’t possibly be more excited about this weekend, because for the first time in years I will be traveling outside of Toronto exclusively for a bookish event: the 33rd Annual Wayzgoose in Grimsby, Ontario.

There are a lot of bookish events in Ontario, but this is the only one I can think of dedicated specifically to the “Book Arts” rather than, say, publishing, reading, or rare/used books. That’s probably why they now boast attendance of upwards 2000 people from all over the world – this isn’t exactly an opportunity to sell books or schmooze so much as it’s a genuine festival, a celebration of the arts that bring you printed books: letterpress printing, paper making, bookbinding, marbling, calligraphy and more. I look forward to demonstrations and displays as well as the opportunity to spend money on one-of-a-kind books from odd and out-of-the-way bookmakers.

I started this post, by the way, with the impression that the Wayzgoose was founded and hosted by Erin, Ontario’s Porcupine’s Quill Press, but after some research I discover this is not the case. The Wayzgoose is entirely independent, officially sponsored by the Grimsby Public Art Gallery. My confusion probably stems from the fact that Porcupine’s Quill is enormously supportive of the endeavor, especially as they publish Canada’s only dedicated Book Arts journal, the Devil’s Artisan. It is through Porcupine’s Quill that I learned of the event and because of their cheerleading that I am so psyched about the event – and probably also because of one or two excellent wares they promise to have available: a new issue of D.A. and a new facsimile edition of George Walker’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

And to wander further off on a tangent, Porcupine’s Quill seems to be making a stab at replacing Gaspereau Press as the country’s most talked-about craft press – not only are they running a social-media contest right now to promote Alice’s Adventures, but I spotted their little ad in the print edition of this weekend’s Globe and Mail books pages. I choose to interpret this as evidence of a surge of interest in the book arts. Who’s with me?

Well nevermind, but I will be in Grimsby on Saturday, and I hope some of you will be to!

April 20, 2011

Pigeon English & Voice

After a hiccup earlier this month, I finally went back and plowed through the last fifty pages of Steven Kelman’s promising debut novel, Pigeon English. It was difficult, but not because of the quality of the book – this will not be, per se, a review proper, but let me just assure you right off the bat that this is a good book, whatever else I will say about it below. No, it was difficult because it is a tragic book, and at the moment I am feeling particularly unable to deal with stories in which horrible things happen to children. This isn’t much of a spoiler, by the way. The first page opens with one child’s ruminations on the blood leaking out of another, dead, child.

After a hiccup earlier this month, I finally went back and plowed through the last fifty pages of Steven Kelman’s promising debut novel, Pigeon English. It was difficult, but not because of the quality of the book – this will not be, per se, a review proper, but let me just assure you right off the bat that this is a good book, whatever else I will say about it below. No, it was difficult because it is a tragic book, and at the moment I am feeling particularly unable to deal with stories in which horrible things happen to children. This isn’t much of a spoiler, by the way. The first page opens with one child’s ruminations on the blood leaking out of another, dead, child.

Kelman’s novel is set in a ghetto where 11-year-old Harrison Opoku has settled after immigrating to England from Ghana with his mother and older sister. Unlike in so many other books about poverty and social decline depicted in terms of the unreadably tragic horrors they wreak on children – Heather O’Neill’s Lullabies for Little Criminals comes immediately to mind – Opoku’s personal history isn’t terribly dark at all. He has a father, baby sister and grandmother back in Ghana who are just waiting for their turn to join the rest of the family in the UK. Kelman hasn’t burdened Harri with abusive caregivers, any history of sexual abuse, drug addiction, child labour, early loss – none of that. He’s just an observant and adventurous kid taking in his new society as it comes to him. He seems like he might come through whatever trials this impoverished English neighbourhood might offer him in good shape.

The story is told in the first person by Harri with only occasional (and ill-advised) digressions into the head of a pigeon. I found this choice of voice – Harri, not the pigeon – problematic. I don’t take issue in general with authors who choose to tell a story in a voice completely unlike their own. Authors who choose to give a voice to minorities, the mentally ill, murderers, animals, or cans o’ beans are welcome to do so regardless of their own age, colouring or species. In doing so they often give voices to segments of the population utterly under-represented in fiction. Kelman’s background growing up in an estate similar to Harri’s even gives him some insider credibility – he knows what it is to be a kid in a housing project. Very well.

Regardless, I found myself skeptical of the direction Harri’s story took, a doubt that would have been dispelled if I’d felt the author was a little more representative of the character he was giving voice to. I felt there was a disconnection between Harri’s relatively stable situation and innocent voice, and the fate that eventually befalls him. Why Harri, who has friends, family and a strong sense of self, should have become embroiled with the Dell Farm Crew isn’t entirely clear to me, unless we assume powerful gangs offer equal temptation to all young boys. Though doesn’t that to some extent dull the argument sometimes made that the young men in violent gangs are “troubled”; that gangs are the last refuge for a culture of poor, powerless boys without strong paternal guidance? Certainly the implication offered by HBO’s stunning (and utterly believable) series The Wire is that young people are sucked into the violence of the “corners” are forced there by deteriorating social conditions and horrifying personal circumstances. Harri, coming from a place of relative strength, doesn’t seem to belong there.

Kelman’s thesis can be said to be, then, that this can happen even to smart, resourceful young men who just happen to live in the wrong place and who turn up at the wrong time. The real tragedy of Harri’s story is that he’s fundamentally a good kid, and still gets eaten by the estate. I’m skeptical. Many people, every day, survive the ghettos, projects and housing estates of deteriorating Western cities. Why not Harri? Is this just a story of bad luck? I’d feel reassured if I knew the author really had been there. Given a claim that seems dubious to me, I’d appreciate a claimant with more authority. It would leave me with a better sense that Pigeon English is a book about the rot of Western society, rather than it’s being another addition to the growing ranks of tragedy-porn.

But enough of that. I maintain the book is basically good. It has other virtues, and I encourage you to read the review offered by Kerry Clare at Pickle Me This. Kelman has a clear talent for evoking and provoking, and I’d eagerly check out whatever he has to offer next.

April 18, 2011

Objects Found in Books

One of my favourite bookish news stories from the last month is this one in which a typed letter from Robertson Davies to New Canadian Library co-founder Malcolm Ross was found in the pages of a book bought at a Halifax Salvation Army shop for $1. This kind of thing actually happens all the time, though perhaps not so often with such bright lights of Canadian literary history. From as far back as books have been produced in codex-form, people have been putting flattish things in between the pages and have forgetting them there. One of the great pleasures of buying second-hand books is finding them again.

Sometimes this kind of ephemera can be quite valuable to collectors and to libraries, a hunger wonderfully novelized by A.S. Byatt in Possession. More often it is simply another layer of history passed down through the object to the new reader. Old bookmarks, receipts, notes and letters; even pressed flowers, locks of hair and ribbons give a used book a unique character that separates it from other copies of the same book. Even this can be of value to a book history scholar (again, beautifully novelized by Geraldine Brooks in her recent People of the Book), but personally I love the way it gives me my own mystery to solve; good for nothing, probably, but telling a story.

Two great-aunts of mine, both spinster librarians who kept up friendly correspondence with writerly contemporaries of theirs, were great clippers and hoarders. Few books I’ve inherited from them are free from newspaper clippings, letters and photocopied notes from other books. An old biography of Rudyard Kipling contains clipped Kipling poetry from a 1920s newspaper, while my facsimile of John Gerard’s 1633 Herbal has notes on the authors photocopied from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Two great-aunts of mine, both spinster librarians who kept up friendly correspondence with writerly contemporaries of theirs, were great clippers and hoarders. Few books I’ve inherited from them are free from newspaper clippings, letters and photocopied notes from other books. An old biography of Rudyard Kipling contains clipped Kipling poetry from a 1920s newspaper, while my facsimile of John Gerard’s 1633 Herbal has notes on the authors photocopied from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

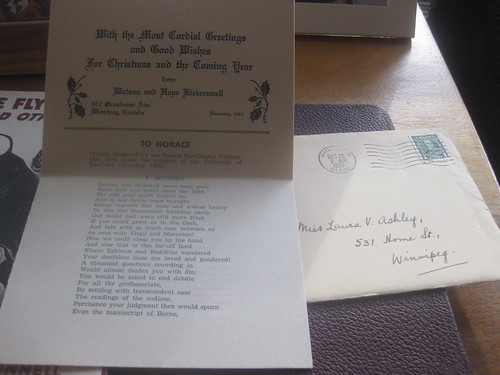

One aunt in particular seems to have been a friend of the Western Canadian author Watson Kirkconnel. One of my favourite ephemeral findings is a Christmas card, sent in 1935, from Kirkconnel and his wife featuring a poem, “To Horace”, otherwise unpublished. Though Kirkconnel is utterly unknown and out of print today, the addition of this cheerful little relic of the past makes this book (a limited edition copy of his Flying Bull and Other Stories) one of my favourites. Kirkconnel has posthumously become an imaginary family friend, part of my own past. Other letters and clippings from Kirkconnel adorn other books in my library: I like to invent and exaggerate the dimensions of my aunt’s relationship with the once-great author. The artifacts give me that right, I think.

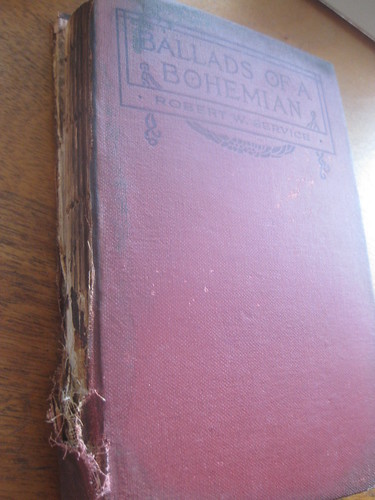

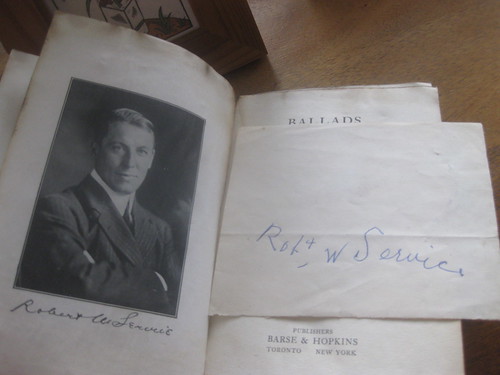

Once when I was very young I snuck into a broken-down house known to me in order to “liberate” a very musty and dilapidated old tome I saw there. I imagined that, being an old broken-down house, all printed materials found within must necessarily be mysterious, valuable, and possibly occult. I was both very wrong and very right. The book, Robert Service’s Ballads of a Bohemian, is utterly worthless because of the condition it is in – torn, moldy, and even slightly burnt-up. On the other hand, it appears to contain a slip of paper bearing Service’s signature. The book is not signed directly, but the name is written on a separate slip found facing the portrait of the author. Is it really the author’s signature? I have no idea. It is not a clean and tidy signature, and looks instead to have been made by someone very advanced in years, or in deteriorating health. That said, that nearly rules out its being a copy or forgery. Any attempt to mislead would surely be closer to the “official” thing. But why else would it be there? This is my bookish mystery. The myth associated with my finding and retrieving this book certainly sounds better if the tale ends with its being a signed copy. Well, it’s my unique relic so, again, I reserve the right to tell the story. It’s signed, my own treasure.

Once when I was very young I snuck into a broken-down house known to me in order to “liberate” a very musty and dilapidated old tome I saw there. I imagined that, being an old broken-down house, all printed materials found within must necessarily be mysterious, valuable, and possibly occult. I was both very wrong and very right. The book, Robert Service’s Ballads of a Bohemian, is utterly worthless because of the condition it is in – torn, moldy, and even slightly burnt-up. On the other hand, it appears to contain a slip of paper bearing Service’s signature. The book is not signed directly, but the name is written on a separate slip found facing the portrait of the author. Is it really the author’s signature? I have no idea. It is not a clean and tidy signature, and looks instead to have been made by someone very advanced in years, or in deteriorating health. That said, that nearly rules out its being a copy or forgery. Any attempt to mislead would surely be closer to the “official” thing. But why else would it be there? This is my bookish mystery. The myth associated with my finding and retrieving this book certainly sounds better if the tale ends with its being a signed copy. Well, it’s my unique relic so, again, I reserve the right to tell the story. It’s signed, my own treasure.

To beat that poor old horse, it would be a real shame if the digital future inadvertently limited or destroyed the preservation of ephemera. Casual insertion of things into day-to-day books has brought a wealth of everyday artifacts to us. It goes without saying that nothing can be inserted into an ebook, but moreover, it’s more rare for things to be inserted into valuable or collector books. A theoretical future where the remaining printed books are more highly valued as artifacts is one where people are less likely to stick any old thing between the pages. Casually read books are the ones which come to us with the heaviest signs of their history. I was struck while re-reading Frank Herbert’s Emperor of Dune by a scene in which a high-tech book is stolen and then, between the pages, a dried flower is found. The discovery is significant to the characters but also oddly anachronistic. Even in the year 13,000 we’re to presume that the book has remained as much a vehicle for material pieces of life as much as of information.

Of course the ephemera itself is disappearing more quickly than the book in any case. Newspapers? Letters? Recipe cards? Relics of past generations moreso than books. But I’ll miss, you know, receipts, bookmarks and flowers. Wouldn’t you?

April 15, 2011

The Sadness of Books We Can’t Sell

There’s a depressing side to returns season. It comes near the tail-end of the fiscal year, when we can delay the inevitable no longer and have to send back books which we’d been holding on to as long as possible for sentimental reasons; books which “should” sell. What’s maybe more depressing is that books that don’t sell usually fall into very specific categories, and so maybe as booksellers we should learn simply not to order from these lists. After all, our job isn’t to snobbishly insist readers should be reading one thing or another, it’s to provide them with a good choice of things they might be interested in. So why, after years of failing to sell some of these books, do we keep ordering them? Optimism, I suppose.

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

This is an especially sad category considering the wealth of absolutely amazing Canadian YA lit being published. I have no doubt that companies like Groundwood Books do stunningly well through the school and library markets, but we sell precious none of them off the shelves. Children’s books – picture books – do very well, probably because it’s parents who buy them. YA fiction featuring vampires, wizards, witches, time travelers and talking animals also do just fine. Classic children’s novels like The Secret Garden, Five Children and It, Swallows and Amazons and so on also do fine (though, again, often purchased by grand/parents).

But good, insightful plain fiction aimed at young adults? Forget it. Not that that stops us from filling the shelves with Glen Huser, Polly Horvath, Alan Cumyn, Tim Wynn-Jones and Paul Yee. We just have to send them all away again at the end of every year.

Chinese Literature

Chinese Literature

Literature in translation goes through fads and phases until a region has accumulated a critical mass of Nobel Prizes or Booker Internationals. These days Middle Eastern literature is starting to come into vogue. And, you know, great! Fabulous books like Al-Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building and Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun are getting well-deserved love, and Tablet & Pen: Literary Landscapes from the Modern Middle East ed. Reza Aslan has been a surprise best-seller for us.

But oh man, China. Its day in the literary limelight has not yet arrived. Gao Xingjian won the Nobel prize in 2000, the first Chinese writer to do so, but I defy you to name offhand a single book of his (I had to look it up on Wikipedia, and even then nothing looked familiar). We do bring the translated books in – A Cheng’s King of Trees, Bi Feiyu’s, Three Sisters, Jiang Rong’s, Wolf Totem and much more – but they don’t go back out again. Tuttle Publishing is even doing wonderful new editions of “Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese Literature” – The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey Into the West – which we have valiantly kept on the dusty shelves these past ten years, to no avail.

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

You’ll be surprised to know that Russian literature didn’t die with Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn! Despite forays into internationally renown territory like Victor Pelevin’s contribution of Helmet of Horror to the Canongate Myth series (which also brought us, among other things, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad), I think I’d be safe in saying that post-soviet Russian novels are being completely ignored by Western media, critics and readers.

But there’s plenty to be had. NYRB has published some of the best offerings (though, see below), including Tatyana Tolstaya’s The Slynx and Vladimir Sorokin’s The Ice Trilogy (which I cannot wait to read, for reals). Plenty of Pelevin’s books have been translated and published by big, international publishers. But buyers? Well, not here.

NYRB Classics

NYRB Classics

We don’t sell none of these, so maybe this isn’t a great example. But we do tend to order absolutely everything they publish because their books are so damn good, so when it comes time to return and we’re sending back most of them, it looks particularly bad.

NYRB publishes some truly under-represented bodies of work, like literature in translation outside of your usual Nobel laureates and international bestsellers and literature from the 20s and 30s not written by Faulkner, Hemingway or Fitzgerald. Perhaps, then, this is why they tend to be slow in the selling. It’s hard to sell Elizabeth von Arnim as “frontlist” or “new” when she died in 1941 (and doesn’t have the cheerleading squad that Irène Némirovsky has), even if The Enchanted April is in a beautiful new edition and a wonderful book. People haven’t heard of her, and they’re more likely to pick up the new Cynthia Ozick or Eva Hoffman.

Always exceptions, of course. As I mentioned, Arabic lit is all the rage around these parts nowadays, and NYRB brought us Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih, which sells like those proverbial hotcakes.

Oh well. I suppose if it weren’t these books, it would be something else going back! There are so many books and so little time. Maybe when I finish sending all these lovelies away, I can get to work reading some of the survivors!

April 8, 2011

I can YOSS too!

A bunch of smart and dedicated persons (I hesitate to say “ladies”, but I think they might all be ladies) have declared 2011 to be the Year of the Short Story. Now while I don’t think I am very likely to want to spend a year reading nothing but short stories (which is not, by the way, what they are suggesting), I can’t argue with their aim: to bring short fiction to a larger audience.

A bunch of smart and dedicated persons (I hesitate to say “ladies”, but I think they might all be ladies) have declared 2011 to be the Year of the Short Story. Now while I don’t think I am very likely to want to spend a year reading nothing but short stories (which is not, by the way, what they are suggesting), I can’t argue with their aim: to bring short fiction to a larger audience.

Once upon a time I was a heavy short story reader. I am now a light short story reader. The last anthology I read was I read was Neil Gaiman & Al Sarrantonio’s Stories, which I’d say was a mixed success. It certainly contained a couple stories I just loved (notably Neil Gaiman’s The Truth Is A Cave In The Black Mountains and Michael Moorcock’s Stories), and at least one I want to go back to (Jeffrey Ford’s Polka Dots and Moonbeams). But it also had it’s share of silly, hackneyed stories featuring overdone themes – like Walter Mosley’s Juvenal Nyx (oh good, another angsty, vampire-with-a-soul story) and Joanne Harris’s Wildfire in Manhattan (gods of old WALK AMONG US).

But this is the nice thing about short stories. Even within one collection, you can taste such a variety of persons, places and ideas. They’re easy to dip into and out of, and to go back to. Any collection is bound to have at least one story you’d recommend to a friend, whereas I’m not sure I’d ever recommend a chapter of a book to anyone. They offer a level of accessibility without triviality.

I’ll put my money where my mouth is – per YOSS suggestion #1, I am buying more short stories. And last night, this came in the mail!

Check it out – my Limited Edition (59/300) copy of Machine of Death: A Collection of Stories About People Who Know How They Will Die ed. Ryan North, Matthew Bennardo & David Malki ! I’ll be honest, I don’t know any of the authors, but each story is illustrated by a cartoonist, many of whom I am a big fan of. But no, I didn’t buy it for the pictures. That might have been an excuse (that and the Certificate of Predicted Death), but it’s also a chance for me to sample stories by a variety of writers who I might otherwise never encounter, as recommended to me by cartoonists I trust. And, you know, then there’s the pictures. And the chance to have them all signed next month at TCAF.

The short story world is full of fun gems like this! I hope you’ll seek one or two out this year too. Sometimes the most interesting reads are off the beaten track [of novels]!

April 6, 2011

Upcoming Book Geekery

It’s a quiet time of year here for us at the bookstore, but that means a lot of quiet, intimate time with the publisher catalogues. A dangerous time of year, as you can imagine. I am additionally imperiled by the fact that I will be on maternity leave by mid-July this year, and so I’m feeling a need to pre-order all kinds of things before I’m “out of the loop” for a year, as it were.

What kinds of things? Well.

Titus Awakes by Mervyn Peake & Maeve Gilmore

Titus Awakes by Mervyn Peake & Maeve Gilmore

I’m skeptical about works published post-humously, generally. Especially things possibly never intended for publication based on “manuscripts” or worse still “fragments” found years later by family members.

The circumstances surrounding this books “discovery” are also a bit suspect. Peake’s widow, Maeve Gilmore, wrote or finished a manuscript based on Peake’s notes in the 1970s, but the manuscript was “lost”. In 2010 the manuscript was “found” in a family attic – just in time for Peake’s centenary! Convenient, no?

Even still, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy (now, apparently, a tetrology) is one of my most beloved works of literature, and I can’t resist more.

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

How can anyone not be excited about a new Murakami novel? Goodness knows the Japanese lost their minds over it, apparently buying up almost 450,000 copies of the first volume (it was published in three parts in Japanese) before it was even published.

I adored Kafka on the Shore and Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. I tend to use the term “postmodern” disdainfully, but I’m a complete hypocrite – in reality many of my favourite modern novels are way out on the wacky fringe of postmodern surrealism – Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Murakami, Rushdie, Marquez. That 1Q84 is being described as Murakami’s “magnum opus”, and “a mandatory read for anyone trying to get to grips with contemporary Japanese culture” just adds to the appeal. 1000 pages plus of a “complex and surreal” narrative? Sign me up!

Il Cimitero di Praga by Umberto Eco

Il Cimitero di Praga by Umberto Eco

Okay, this one’s a bit cheaty because what I’m really looking forward to is the eventual (and inevitable) English translation, The Cemetery of Prague, which hasn’t been published yet.

The story of the genesis and history of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion is a great one for book history lovers. In Umberto Eco’s hands, it’s a tale of intrigue and conspiracy. The book has come under some criticism for blurring some lines between genuine antisemitism and fictional antisemitism, but I don’t personally believe for one second that Eco is genuinely antisemitic. He has said: “I’m interested in recounting how through the accumulation of these stereotypes the ‘Protocols’ were constructed. [..] My intention was to give the reader a punch in the stomach.” and I believe him.

That the plot of Alexandre Dumas’s Joseph Balsamo also plays a large part in the plot of this novel is also a HUGE draw. Surprise!

How imminent is an English translation? No idea! But I refuse to miss it just because I’m sitting at home with my kids.

Climate Capitalism: Capitalism in the Age of Climate Change by L. Hunter Lovins & Boyd Cohen

Climate Capitalism: Capitalism in the Age of Climate Change by L. Hunter Lovins & Boyd Cohen

I’ve mentioned I’m an environmentalism nerd, right? One of Hunter Lovins’s previous books, Natural Capitalism, pretty near changed my life. And true story: it was for some time my life’s ambition to work in carbon trading. You know, where companies can buy and sell carbon credits under a cap-and-trade system. Okay, maybe a little obscure for the book crowd.

In any case, the environment might not be the biggest hot political topic of the minute anymore, but I assure you the problems didn’t fix themselves when we lost interest again. This year has actually been a wonderful year for good, readable books on the current and future movements in environmentalism – Tim Flannery’s (most famous for The Weather Makers, but who is also responsible for a fabulous illustrated bestiary of extinct animals called A Gap in Nature) new book Here On Earth also just hit shelves, and Ray Anderson’s Confessions of a Radical Industrialist is at the very top of my must-read pile. I’m happy to report that the serious discussion about climate change has moved beyond fear mongering vs deniers, and is in the happier territory of Okay But What Can We Do, Realistically. I love this territory. I’m a big one for plans of attack.

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton

Beaton’s previous collection, self-published and distributed by Topatoco, was more of a sampler; something thrown together to sell at conventions and get the word out. It was silly successful – Beaton won the Doug Wright Award for Best Emerging Talent and has subsequently been published in the Walrus, the New Yorker, The National Post and, I’m sure, more.

No surprise, she’s been picked up by Montreal graphic novel game-changers Drawn & Quarterly. Drawn & Quarterly produce the most beautiful books, and though I expect their Hark! A Vagrant collection will retread a lot of the same material as appeared in Never Learn Anything from History, it’s bound to be better put together in every possible way. If their previous publications are anything to go by, there might even be a limited edition signed/numbered w/ insert edition. Exciting!

I have my little fingers crossed that they might even have some copies ready by TCAF this May – but just in case, my order is in.

Anyone else want to share? Any upcoming releases have you super excited?