December 31, 2009

Three Quick Reviews

I’ve been lax in reporting my reads this season. I’ve been lax in reading as well – I think my final total for the year is something like 25 books. I have three excuses: 1) a small child who does not like to share my attention 2) a heavy schedule of school-related reading and writing and 3) once again I managed to get stonewalled by some long, boring book that I couldn’t manage to read more than 2 pages at a time of. I need to learn to abandon books sooner! On the one hand there’s the question of discipline, of needing to try extra hard to get through dry, long or difficult books. But really that doesn’t give any old book the right to torture me for long hard months. I have some right to be engaged, don’t I? If I put in the time and the effort to give it a fair shake, I should be allowed to finally throw it down guilt-free. Perhaps this should be my New Year’s resolution. I resolve to not feel guilty about giving up on books that I’ve given a solid chance to.

Anyway, here are the last three books I’ve read:

This book here (Hunter’s Oath by Michelle West) was exactly as good as it looks. It came hesitantly recommended by a coworker of the author’s. I was, at the time, looking for undiscovered gems of Canadian fantasy. This was not one. I have a longer post to make about how fantasy as a genre has missed the point of magic as a literary tool, and this book will make an excellent example of what not to do. For a simple fantasy novel, this book took me an extraordinarily long time to read because I was continually bored with it. Oh well.

The book on your right (Airborn by Kenneth Oppel), on the other hand, was wonderful. Set in a slightly alternative past where the rich fly in luxury zeppelins rather than steamships like the Titanic and where the Lumiere Brothers were triplets, Airborn is everything you would want in a book to recommend to a younger person, or an older person who enjoys the freshness and optimism of young adult literature. Loved it to pieces!

The book on your right (Airborn by Kenneth Oppel), on the other hand, was wonderful. Set in a slightly alternative past where the rich fly in luxury zeppelins rather than steamships like the Titanic and where the Lumiere Brothers were triplets, Airborn is everything you would want in a book to recommend to a younger person, or an older person who enjoys the freshness and optimism of young adult literature. Loved it to pieces!

And finally, on the left you will meet the book that stalled me out for two months, The Hanging of Angelique by Afua Cooper. This was a tremendous disappointment. There’s no question as to the value of the scholarship here, but the presentation, especially coming from an author with experience as a poet, was utterly lacking. The book felt long, repetitive, and boring. We know right from the get-go exactly what will happen: A slave, Angelique, will set fire to her owner’s house causing the big Montreal fire of 1734. She will be arrested, tried, tortured and hung. So what does the book add in the telling? Some details, often tangential. Archival evidence and some history. No drama, revelation, insight. I can see the value of this work to research, but heavens it lacked as a straight-ahead read. I almost wish she’d just approached the material differently, maybe saving us the details of the event for a “climax” of the story, rather than giving us everything we need to know in the first two chapters and leaving the rest of the book to serve as an itemized list of evidence.

And finally, on the left you will meet the book that stalled me out for two months, The Hanging of Angelique by Afua Cooper. This was a tremendous disappointment. There’s no question as to the value of the scholarship here, but the presentation, especially coming from an author with experience as a poet, was utterly lacking. The book felt long, repetitive, and boring. We know right from the get-go exactly what will happen: A slave, Angelique, will set fire to her owner’s house causing the big Montreal fire of 1734. She will be arrested, tried, tortured and hung. So what does the book add in the telling? Some details, often tangential. Archival evidence and some history. No drama, revelation, insight. I can see the value of this work to research, but heavens it lacked as a straight-ahead read. I almost wish she’d just approached the material differently, maybe saving us the details of the event for a “climax” of the story, rather than giving us everything we need to know in the first two chapters and leaving the rest of the book to serve as an itemized list of evidence.

So there you go, a little catch-up. I am still reading Nikolski as well as Eleanor Wachtel’s More Writers and Company (a purchase from last year’s Trinity College Book Sale). Both will warrant longer thoughts – but will have to wait for the new year!

November 30, 2009

Book Prizes and Book Recommendations

I can’t overstate how excited I am about tomorrow’s Canada Reads 2010 announcement. I have it on my calendar and plan to stay home from Miss Margaret’s drop-in centre in order to hear it, pen and paper ready to scribble down my order list. While the competition aspect of Canada Reads is definitely good fun, what I love best about it is simply receiving the recommendations. Does that sound strange? I find it very difficult to get reliable literary recommendations. It isn’t that there aren’t enough recommendations flying around out there, it’s that there are generally too many.

The seasons’ Best of 2009 Picks are a case in point as far as I am concerned. Every publication with a book reviewer publishes a “Top X Books of the Year” right around Christmas, and I find these lists utterly useless. 100 best books of the year? How are there even enough books published in a year for 100 of them to carry the title of best? I am not a prolific reader as far as bookish folks go – at best I might read 40 books in a year, more often I read 20-25. I can’t absorb 100 books in a year, or even decide which of them to dip in to. I need a short list. Best book of the year. If you read one book this year, make it this one.

That, of course, is something literary prizes can be good for. The Booker Prize winners for the last few years have been decent reads, but I’ll admit it’s pretty clear to me that the Giller juries and I have very different opinions on what makes a good book. Canada Reads is different. Although they’re limited to Canadian books, the wider sweep of time reaches more nooks and crannies than a conventional annual book prize. Because of the populist focus of the competition, they seem to go out of their way to represent a bit of everything: something small press, something funny, something a little strange, something that was overlooked the first time around, something classic but forgotten. And probably most importantly, they aren’t trying to find the best book under any technical criteria, they just want to pick a book they’d feel safe recommending to just about anyone. Be still my heart, recommendations actually intended for reading pleasure.

I even have this thought that I might bundle up Miss Margaret tomorrow and head down to the CBC building for the little meet-and-greet at noon. I’m sure I’ll have at least one of the chosen books on my shelf already, and it’s always fun to have signatures inscribed. Does anyone else have a similar thought? I started this blog last year after having a great time discussing Canada Reads 2009 all over the bloggosphere – I’d love to do the same this year, and maybe meet some (more) of you.

Glee!

October 21, 2009

Into the Sci-fi Ghetto with Margaret Atwood

My first and only prior foray into the work of Margaret Atwood was in high school when I was made to read Cat’s Eye. I hated it passionately. I was unable then – and I still retain this “problem” as a reader – to separate liking the characters from liking the book. The most poetic, well-crafted literature in the world will find itself being hurled across the room in my house if I can’t stand the characters, and Atwood’s limp, weak-minded “heroine” Elaine Risley earned nothing but my scorn. I couldn’t bring myself to give Atwood a second chance for almost 15 years.

My first and only prior foray into the work of Margaret Atwood was in high school when I was made to read Cat’s Eye. I hated it passionately. I was unable then – and I still retain this “problem” as a reader – to separate liking the characters from liking the book. The most poetic, well-crafted literature in the world will find itself being hurled across the room in my house if I can’t stand the characters, and Atwood’s limp, weak-minded “heroine” Elaine Risley earned nothing but my scorn. I couldn’t bring myself to give Atwood a second chance for almost 15 years.

The Year of the Flood seemed to me to be a good safe re-entry into Atwood’s work. After all, I do love speculative genres when well-written, and I have a special place in my heart for post-apocalyptic and survivalist stories. The book had been getting excellent reviews elsewhere and so I could also hope for a good read, regardless of genre. I was mildly put off by Atwood’s insistence that she isn’t writing science fiction (a preposterous claim well debunked by Ursula le Guin) but I resolved to give her the benefit of the doubt.

I don’t know if I succeeded. I’m torn now on this book. On the one hand, I enjoyed it. It was quaint, a page-turner and satisfied my bizzare craving for apocalypse scenarios. If it had been written by a denizen of the sci-fi ghetto I’d probably be writing raves right now. But on the other hand I’d been led to beleive by reviewers and Atwood herself that this book represented something else, some higher, more literate thing than mere science fiction. The New Yorker has likened Atwood’s “speculation” to Orwell’s offerings, and Year of the Flood was long-listed for the Giller (though, perhaps tellingly, failed to be shortlisted for any of Canada’s big literary awards).

What it certainly isn’t is anything special. As literary fiction it is a mediocre-to-decent work. On the whole it feels rushed, as if nobody bothered to do a thorough edit. Ren describes Toby with effectively the same analogy twice in the first sixty pages:

“You wouldn’t think it would be Toby … but if you’re drowning, a soft squishy thing is no good to hold on to. You need something more solid.”

“…we trusted Toby more: you’d trust a rock more than a cake.”

Early in the book Ren and Toby speak of each other in nearly whistful tones, as if they’ve played a great part in each others’ lives. Yet when their mutual history finally collides at the AnooYoo Spa, we are told they barely interact and Ren, ultimately, leaves within a few months. I found myself repeatedly faced with similar questions about the characters’ relationships (what was up with Toby and Zeb? Or Amanda and Jimmy? Glen and anyone? Mordis?) and the root of my confusion is ultimately Atwood’s haphazard character-building. Names and positions fail to pupate into fully-formed characters and so they phone in their parts in the story like high school thesbians who only barely learned their own lines. Even the two main characters fail to fully gel. Toby was the more successful of the two protagonists: Ren was a half-believable sketch whose early opinions made less and less sense the more you knew about her.

I also found what other reviewers referred to as “clever” to be quaint at best and more often, lame. Her future is populated with genetic “splices”, creatures created by man and released accidentally or intentionally into the wild. These critters are invariably called by a spliced name – rakunks, (raccoon/skunks), liobams (lion/lams) or wolvogs (wolf/dogs). She makes easy double entendres of the corporate overlords like CorpSeCorpse (get it? CORPSE?) and SeksMart (you know, like SEX) and Saints of most of our twentieth-century Greenies, which frankly seems to overestimate the long-term impact of people like Terry Fox.

Oddly the novel’s “roughness” is discounted as some kind of virtue by Jeanette Winterson’s New York Times review. Apparently “The flaws in “The Year of the Flood” are part of the pleasure…” – I beg to differ. But this is par for the course with Atwood reviews I am learning. The woman can do no wrong, which brings me to my next complaint.

If Year of the Flood isn’t a wonderful literary novel, is it at least good science fiction? Sure, it’s not bad. Nothing special. Science fiction motifs have been used to address Atwood’s themes already, from child abuse (Nalo Hopkinson’s Midnight Robber) to religious cults of sustainability (Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash) to mega-corporate control (Shadowrun, anybody?) But Atwood’s reviewers don’t seem to have any experience or history with science fiction, so they speak of her most mundane tropes as if they’re stunningly innovative insights.

This, I think, is what drove me the most crazy about the book. How can so many reviewers get off calling her “prophetic” for a book that simply re-treads the same material science fiction writers have been working with for the last fifteen years? She surely treads it well enough, but prophetic? Seriously? It’s insulting to the smart, clever, funny and literary science fiction writers out there who don’t have Atwood’s golden glow. Most of all I’m disappointed at Atwood herself, who rather than acknowledging the fine tradition of eco-speculation she is joining, acts as if she has invented the wheel.

So it’s a pretty good book. I guess. Shame about the pretentions, because they pretty much ruined it for me.

September 25, 2009

Reviewish: Therese and Pierrette and the Little Hanging Angel

After only my second foray into the novels of Michael Tremblay (the first being The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant earlier this year), I am a solidly devoted apostle. After this year’s Canada Reads competition I find I am in good company. We in English Canada have been a bit slow on the uptake, I think, but we’re finally cluing in on what our fellow devotees in French Canada have known for thirty years: Michel Tremblay is one of the finest storytellers in the world.

After only my second foray into the novels of Michael Tremblay (the first being The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant earlier this year), I am a solidly devoted apostle. After this year’s Canada Reads competition I find I am in good company. We in English Canada have been a bit slow on the uptake, I think, but we’re finally cluing in on what our fellow devotees in French Canada have known for thirty years: Michel Tremblay is one of the finest storytellers in the world.

Therese and Pierrette is the second book in Tremblay’s Plateau Mont-Royal series, following about one month after the events of Fat Woman. The cast of millions present in Fat Woman have largely taken to the background and we accompany Therese (the Fat Woman’as neice) and her friends Pierrette and Simone as they figure in their Catholic girl’s school.

One of the “complaints” I recall being voiced during the Canada Reads debates is that the structure of Fat Woman doesn’t “go anywhere”, that no clear story is being told – that hasn’t changed. That was never a problem for me; in fact, that is part of the genius of Tremblay’s work. He offers a slice of life, a portrait woven of the characters’ actions, thoughts, memories and digressions that reconstructs so accurately the sensation of living. Any traditional novel-wide narrative structure, of beginning, climax and finale, he intentionally subverts by giving away the ending. Tension created by fights, incidents and dangers is immediately diffused by a omnipresent storyteller’s intervention with a “years later” digression. The effect is that we are not distracted by needing to find out “what happens next” or by being carried away by the plot; instead we can focus on the immediacy of the events. You are drawn into the moment and are free to appreciate the relevance of that paragraph rather than looking ahead to the next event.

This trick of focusing the reader’s attention on the page and words rather than a story is reinforced by the “block of text” formatting which also put some readers off Tremblay’s work. You can not skim his books – not only is it physically difficult to do so but there is no benefit to doing so. The reward is in the moment, not in the cumulative effect of the whole. I have never seen a Tremblay play but I can see how his talent for drawing you into the now could be so engaging on stage. He creates a beautiful moment without it being reliant on a meta-reactions like shock, suspense and anticipation.

That said, I loved returning to the characters from Fat Woman and discovering what has become of them, just as I would enjoy catching up with a friend and hearing how their family is faring. We learn the latest on the playground-guard whom Therese kisses in the first novel, and the fate of Dupliesse the cat, so mortally wounded when last we saw him. Victoire and Josaphat-le-Violon find some closure and we get a brief glimpse at the Fat Woman and her looming infant. Tremblay doesn’t exhaust us with unecessarily melodramatic tragedies and incidents. Life is lived by the inhabitants of his Montreal just as you or I live our lives. It’s charming and inspiring without being syrupy and white-washed.

I bought the entire Chronicles of Plateau Mont-Royal from Talonbooks; six books all told of which I have now read two. I considered diving right into the next one right away but, just as email correspondence can become dry by virtue of its over-immediacy, I think I’d better wait and get some distance before I visit again. The visits are so rewarding that I want to savor them. The lives will sit there and wait for me until I am ready.

July 27, 2009

Visiting from the Land of Books

My maternity vacation is over and I have been back to work at the book room for two weeks now.

I have to confess that I have been cheating on my all-Canadian reading diet. One of the great hazards of working in a book store is of being distracted from the task at hand by any number of new, wonderful and enticing books sitting on the shelf. So while I do have Therese and Paulette sitting on the shelf behind me, 60 pages read, I haven’t been very faithful to it. I keep passing little curiosities, flipping them open and thinking, “well, it is only 150 pages. I can read this before lunch and then go back to something else.”

Most avid readers will tell you that they read four or five books at a time. Me, I try to focus on one. If I don’t apply some discipline then I will play favourites, tending to ignore the harder books I’ve undertaken. But then, a consequence probably of the fact that the harder or more boring books can sometimes take me months to get through, I don’t read as much as some people do. I certainly don’t read as much as I’d like to. In a good year I will read 40-50 books, in recent years (I blame knitting and child-rearing) I’ve barely read more than 20.

Two of the books I have read since being back at work, Books: A Memoir by Larry McMurtry and The Beats: A Graphic History by Harvey Pekar & co. feature autodidactic protagonists whose reading habits are described in the same terms as their hedonistic drug habits (well, maybe not McMurtry’s). They binge, they read obsessively, they escape for weeks, months into libraries and stacks. The great writer is the great reader, end of story.

Two of the books I have read since being back at work, Books: A Memoir by Larry McMurtry and The Beats: A Graphic History by Harvey Pekar & co. feature autodidactic protagonists whose reading habits are described in the same terms as their hedonistic drug habits (well, maybe not McMurtry’s). They binge, they read obsessively, they escape for weeks, months into libraries and stacks. The great writer is the great reader, end of story.

Having modest aspirations to writerhood myself I am therefore critical of my reading habits. Should I read more books? Better books? Am I better served by spending three months slogging through, say, Dostoevsky’s The Adolescent (my nemesis) or by reading back to back 6-8 shorter, more varied titles: some poetry maybe, essays, some more sparse novels? I go back and forth. And I cheat. Most ridiculously, I feel guilty about it.

Scattered and undisciplined as book store life makes me, however, it has its benefits. Customers, not unreasonably, always expect me to have read every book in the store. Is this any good? Have you read this? How does it compare to this? If I didn’t engage in little episodes of literary philandering I wouldn’t be able to bluff my way through these little interrogations quite so well. Customers who know me ask me my opinions without hesitation; they really do assume I’ve read it all. This isn’t as good as having read it all but it is flattering. The reading hasn’t reached full gestation and burst forth in a great literary creation yet but I am an awfully good bookseller. Maybe there’s something to be said about my destiny there.

So am I making excuses for dabbling and cheating and reading little bits all over the map? Probably. This is how I maintain my balance after all, but swinging back and forth between a disciplined assertion that good reading should hurt and a freer spirit of impromptu inspiration. In the end I get both done. Is it any wonder that our great writers (and readers) were all crazy or drug-addled? A person’s reading habits are a case-in-point expression of their neuroses. Does anyone read in a careful and measured way? Maybe that’s what casual readers do. Back at the book store torn between reads like a woman with too many lovers it occurs to me that even when I can’t squeeze many books in my reading is anything but casual. What to read entertains as much of my thinking as the read itself. Good lord. But I’m in good company, I’m learning.

As for blogging, by the way, it is and will be a more sporadic activity from here on in. Between work, reading, school, toddlers and living it has to exist between activities. My apologies if you prefer regiments and reliability! But I’m not gone, and continue to welcome your visits.

July 6, 2009

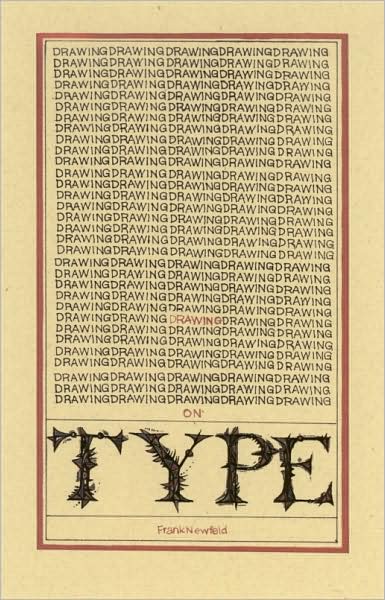

Review: Frank Newfeld’s Drawing on Type

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

Frank Newfeld is an illustrator, book designer, art director and all-around expert in the look, design and feel of a book. He was art director and subsequently a vice-president at McLelland & Steward under Jack McLelland as well as a co-founder of the Society of Typographic Designers of Canada (now the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada). Me, I best knew him as the illustrator of Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie & Garbage Delight, as well as being the guy who judged The Alcuin Society Awards for Excellence in Book Design in Canada. But what becomes evident over the course of his memoir is that he is decidedly not a writer.

I was a little torn about how to approach this review because of that fact. Newfeld has a lot to offer the reader in wisdom, anecdote and experience. That it hasn’t been rendered by a master storyteller doesn’t detract a lot from those elements. His delivery is simple and doesn’t pretend to be more of a stylist than he is, but nevertheless some parts of the book do suffer. The first half of the book is taken up with the first 25 years of his life, most of it spent in the military in Israel. Though he takes some first tentative steps towards his later career as an artist there, the vast majority of this part of the book is a fairly dull, two-dimensional rendering of places and names, the significance of which is not really given to the reader. Names are introduced three to a page, none of whom warrant any character-building. It reads a bit like an acceptance speech, where the aim is to recognize and thank all the influences in a life without giving the rest of the audience any hint of who these people were. This treatment of “characters” lasts for the rest of the book. Almost invariably if someone is identified with a full name it is to “name drop” them and give some laudatory praise, but no description. People who Newfeld is going to speak less well of are discretely identified only by first name, or title.

Even Newfeld himself fails to emerge as a fully-formed personality in the reader’s mind. That said, Newfeld describes the Canadian book trade in very different terms than I think we are used to hearing from those in the know. Unlike the love-in of glosses like Roy MacSkimming’s The Perilous Trade, Newfeld is critical of newer elements emerging in Canadian publishing in the 1970s-1980s. That Newfeld is of the generation prior to the Douglas Gibsons and Dennis Lees of the publishing world is quite evident. There is food for thought for those who would like to question why, if Canadian publishing underwent such a rebirth in the 70s, publishing today looks like a two-player racket pulping out more of the safe and predictable. Food for thought, but Newfeld almost sabotages his credibility with some of his recollections. In particular I found myself flinching through the long blow-by-blow of his difficulties with Dennis Lee and the publication of the children’s poetry Newfeld illustrated. Newfeld’s side of the story is, no doubt, just; but his manner of telling it comes off as petty. He makes nods to being fair and praises Lee when he should, but undermines that carefree tone with smug retellings of some pretty irrelevant incidents. A full-page quote of a bad review Lee garners from the Globe and Mail for one of his post-Newfeld books was totally unnecessary. That he continues to harp back to the same incidents for the next two chapters just reinforces the reader’s sense that Newfeld is being defensive.

Newfeld is, however, at his very best when he is describing a project or a process rather than a person or an event. This, I imagine, is the result of his being (by his account – and I have no reason to doubt him) an excellent teacher who ultimately wound up as head of the illustration program at Sheridan College. The art of design, typography and illustration comes brilliantly to life under his instruction, and his commentary on each discipline is insightful, measured and utterly authoritative. I was especially impressed with his very rational assessment of the use of modern technology in the book trade. I thoroughly expected him to express a curmudgeonly, out-of-date dislike for emerging technologies and found him instead quite open to innovation and experimentation.

This is ultimately what makes the book worth reading – the expertise and care that shine through when he talks about book design and book illustration. He is a genuine connoisseur of material book culture, one with more experience and laurels than many other people alive today. Even when you wonder if he’s being fair to some of the people and attitudes that he criticizes, you see exactly why, formally, he fights these fights. The man understands books in their entirety and is absolutely right when he says publishers are becoming far too focused on the author (and on the design side, the dust-jacket) to the exclusion of the other elements and people involved. This is a debate we don’t see enough of in book circles today. Newfeld is more than qualified to be the one to (continue to) lead the charge and I will, for my part, be taking him to heart in my future academic-and-blogging endeavors. Drawing on Type is a valuable text – and looks absolutely wonderful on my bookshelf.

June 18, 2009

Now That’s Customer Service…

.jpg) During CBC’s Canada Reads broadcasts earlier this year I could be found all over the internet championing what I thought was not just the best book on the list, but one of the very best Canadian books I have ever read, The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant by Michel Tremblay. I was totally devastated when it was voted off the program, but I consoled myself with the knowledge that Michel Tremblay is a rather prolific author and I would have a lot more of his work to read.

During CBC’s Canada Reads broadcasts earlier this year I could be found all over the internet championing what I thought was not just the best book on the list, but one of the very best Canadian books I have ever read, The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant by Michel Tremblay. I was totally devastated when it was voted off the program, but I consoled myself with the knowledge that Michel Tremblay is a rather prolific author and I would have a lot more of his work to read.

In particular I was pleased to see that Talonbooks, the publisher, was offering a Canada Reads special – all six books of the Chronicles of the Plateau Mont-Royal in one handy package for a mere $75. I went down to my local bookstore (also, my place of work) to order it immediately. That was back in February.

I can’t report on exactly what happened after that, but it seemed that Talonbooks’ distributor, Raincoast, was having trouble locating the exact package deal I wanted. Phone calls were exchanged and databases were consulted, and we were assured my order was in progress. Time passed. More time passed. A lot of time passed.

I got the call, finally, a couple of weeks ago. My books were in! I hurried in to the store for my little darlings (paying $45 for the set – I work as a bookseller strictly for the discounts. I am paid in product, I’m afraid.) I only got around to opening the package today. I think, now, I understand what took so long. The package appears to have been lovingly assembled by hand by some industrious employee. A band cut from a 8 x 11 sheet of printer paper secures the books with some help from a bit of scotch tape. The cellophane wrapping is – I am fairly sure – Saran Wrap, also secured with scotch tape, liberally applied. The six books are pulled from the shelf in various states of shelf wear, some having been there for some time.

But I am thrilled none the less. I suspect that with Fat Woman‘s early exit from the challenge Talon gave up hope of having a great bestseller on their hands and withdrew the special. I’m sure they were surprised to get my order but, as good and honest bookpeople, fulfilled it anyway on a to-order basis. Somehow I like it better this way – I am left with the distinct impression of having been personally served.

May 21, 2009

The Smart Guy: Hero or Villain?

Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It In The Bush, that lonely work of early Canadian literature, has a lot to pick apart for the modern reader. While being generally well written and amusing it is hard to ignore the prejudices of its period that leap off every page. Moodie and her husband aren’t so much “roughing it” as they are “complaining about it”. In an era of cholera outbreaks, crop failures, financial ruins and social upheavals Moodie seems chiefly astounded at how hard it is to find good help in the new world, and at how often her new neighbours swear. By page 160 she finally breaks down and has to do some manual labour herself and seems shocked that there is any virtue in it. Despite professing to have come to love her adoptive country she nevertheless speaks with nothing but disdain for a good number of its inhabitants, the Loyalist Americans and the Irish especially.

Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It In The Bush, that lonely work of early Canadian literature, has a lot to pick apart for the modern reader. While being generally well written and amusing it is hard to ignore the prejudices of its period that leap off every page. Moodie and her husband aren’t so much “roughing it” as they are “complaining about it”. In an era of cholera outbreaks, crop failures, financial ruins and social upheavals Moodie seems chiefly astounded at how hard it is to find good help in the new world, and at how often her new neighbours swear. By page 160 she finally breaks down and has to do some manual labour herself and seems shocked that there is any virtue in it. Despite professing to have come to love her adoptive country she nevertheless speaks with nothing but disdain for a good number of its inhabitants, the Loyalist Americans and the Irish especially.

What surprised me, however, was that the grounds on which she repeatedly claims superiority over her neighbours was so familiar to me. Literacy, she tells her American neighbour. She, Moodie, can expect a certain reverence from her neighbours and her servants not because of her colour, wealth or nationality, but because of her education (putting aside for today the glaring fact that her education is the privilege of her colour, wealth and nationality).

It is not very fashionable today to claim superiority over another person for any reason whatsoever, let alone for reasons stemming from socioeconomic happenstance. And yet I can’t help but think that our attitudes towards the superiority of the literate person have changed only in how we voice the attitude: now the uneducated person has our sympathy and our pity, and we feel responsible for raising them up out of their ignorance. The story told by Western literature still goes that the hero, the good guy, is the guy with the book in his hand.

This narrative is especially glaring in stories about disenfranchised minorities: the poor, the brown, the unenlightened. Consider two recent, critically lauded examples: Larry Hill’s The Book of Negroes and Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang. Both books are biographies of heroes who rise beyond their difficult circumstances and score one for the little people, and in both cases the hero is set apart from their peers by their literacy. Hill’s Aminata is as well read as any educated aristocrat and it earns her every protector and defender she has in her story. Carey’s Ned Kelly, meanwhile, is literate enough to write his own history and is depicted as hauling a worn old copy of Lorna Doone through all his trials and tribulations. Reading is a great power wielded by these characters and it is the magic that gives them their break.

Of course, literacy is a great power and for that reason it is rightfully identified as one of the pillars of a strong, fair, free society. Yet when expressed by Susanna Moodie as a superiority I find myself questioning my literate person’s worship of the printed word. To what extent is this idea that literate = superior a cultural assumption made by a society which hails the (European) printing press as the pinnacle of civilization? Would we have as much respect for an illiterate hero?

How interesting also that the hero of literature is a learned one, while in real life the smart guy is still an object of distrust and ridicule. Neal Stephenson’s Anathem, in one of its more brilliant moments, has a hilarious scene in which the scientist-monks cloistered in their concent (a sort of convent – not a typo) are drilled in the many ways society has vilified and objectified the learned man in order to gain back some power from him. The learned man as wizard. The learned man as conspirator. The learned man as bearer of fire and bringer of Armageddon. We don’t even have to look to literature for precedents (in fact, we’re better off not) – I am given to understand that the President of the country next door takes an awful lot of flack on a daily basis for being smart. Hide the books and the Dijon if you want to avoid being beat up at recess.

There seems to be a disconnect between our literati and our popular culture. Susanna Moodie made no headway trying to explain to her American neighbour why her education entitled her to greater respect – the neighbour still felt she was a useless old country lady who wouldn’t survive two winters in Canada. Are our contemporary writers suffering from the same blind spot? Would Aminata Diallo have really won all those allies with her brain for books, or would she have been put down extra-hard because of the impertinence and the threat it represented? Is the bookish hero just a collective fantasy drawn up by bookish people for bookish audiences?

April 17, 2009

Not-so-micro-review of Widdershins

I know I said I wasn’t interested in reviewing books, but I have to post something about Charles de Lint’s Widdershins and as much as it pains me to say so, there wasn’t enough to the book to draw out a longer post. So here we go with the review.

Charles de Lint is an old favourite of mine, a writer who meant a lot to me in high school and who I can still read without flinching too much. I think Fantasy as a genre needs some defenders in literary circles and I had hoped that Widdershins would give me a little platform off which to launch a few rants about the lack of respect the speculative genres get. But Widdershins is not the book to hold as a case-in-point for Literary Fantasy.

Charles de Lint is an old favourite of mine, a writer who meant a lot to me in high school and who I can still read without flinching too much. I think Fantasy as a genre needs some defenders in literary circles and I had hoped that Widdershins would give me a little platform off which to launch a few rants about the lack of respect the speculative genres get. But Widdershins is not the book to hold as a case-in-point for Literary Fantasy.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with his work, Charles de Lint is best known for being the undisputed king of “urban” or “mythic” fantasy. This means his books take place in the “real” world, or one that looks just like it. The fantastic elements are usually gently treated, introduced in appropriate ways and used as metaphors for complex human issues like child abuse, addiction, art or domestic violence. Many of his books, especially the recent ones, take place in and around a city de Lint has created called Newford, and it is with Newford that my qualms begin.

By the time Widdershins was written, Newford has been the backdrop for one too many stories. At this point in de Lint’s career, nearly every character in the city has had a Close Encounter of the Spiritual Kind and they are all entangled in each other’s lives. Despite some backpedaling to explain why Newford is such a mythic hotspot (the spirit realm is closer to the human realm here, magic draws to magic, etc.) the supersaturation of magic has almost trivialized the device. The mystery and metaphor are lost when Newford crossed the line from “real city” to “magical world”. De Lint seems aware of this, and in his preface to the book he offers a sort of apology for coming back to these characters and this story again. But one last story needed to be resolved, he tells us. Fans demand it. So in essence, Widdershins is fan service.

I really wish he hadn’t. Or, at least, I wish I had given this one a miss. The first half of the book (almost 300 pages worth) is loaded down with exposition and back-plot explanations (“Oh yah, that’s Christiana, my brother’s shadow (see: Spirit In the Wires)” or “My sister was a dog and tried to kill me but now we’re cool (see: Onion Girl)…”) and the middle hundred pages are devoted to name-dropping every powerful and awe-inspiring character in the world. De Lint seems to be trying to call up an epic finale to his Newford books by invoking every power he created along the way, but the result of so many “big names” on screen is that they all seem trivialized.

The Big Issue he tackles (aside from Jilly’s abusive childhood, which he already dealt with better in Onion Girl) is a good one – the revenge of the native North American spirits against the invading European spirits (and humans). Restitution for what Europeans did to those who came before them is an entirely unresolved real-world issue that de Lint spins very sympathetically, but the actual plot resolution is weak and anticlimactic. I find it unlikely that hundreds of years worth of seething anger is likely to evaporate the way it did on-page. There’s a lost opportunity here that might have been better handled if it hadn’t been approached in a book that already had too much baggage.

Now, on the positive side of things, there’s no evidence that de Lint has weakened as a writer at all. Widdershins reads like an ill-advised project, but he brings to it the same excellent storytelling and character building that he is known for. De Lint is not a “poetic” writer – I couldn’t find a good prose excerpt to demonstrate his great eloquence because that’s not really his thing. But, probably mindful of this, he doesn’t make any embarrassing attempts at high falutin and flowery imagery filled with misappropriated words and tired old cliches like some writers I could mention. He focuses where his strengths lie: dialogue, character building and action. His characters are so fully realized and unique that I can almost forgive him for coming back to them again and again. It’s hard to leave old friends.

Now, on the positive side of things, there’s no evidence that de Lint has weakened as a writer at all. Widdershins reads like an ill-advised project, but he brings to it the same excellent storytelling and character building that he is known for. De Lint is not a “poetic” writer – I couldn’t find a good prose excerpt to demonstrate his great eloquence because that’s not really his thing. But, probably mindful of this, he doesn’t make any embarrassing attempts at high falutin and flowery imagery filled with misappropriated words and tired old cliches like some writers I could mention. He focuses where his strengths lie: dialogue, character building and action. His characters are so fully realized and unique that I can almost forgive him for coming back to them again and again. It’s hard to leave old friends.

De Lint has a new novel out, The Mystery of Grace, which is entirely self-contained and free from Newford. With any luck this will bring out the best of de Lint’s appeal again. There is no reason why his books shouldn’t stand free of the usual criticisms lobbed at frivolous writers of genre books. He is as good a story teller as Guy Gavriel Kay and Neil Gaiman, both of whom seem to enjoy some mainstream appeal these days. Perhaps I can revisit de Lint later this year and present a review which will stand as a better defense of the genre than the unfortunate Widdershins.

April 8, 2009

Robertson Davies and Formidable Women

Let me start this with a disclaimer.

I am unashamedly a huge, dedicated, dyed-in-the-wool Robertson Davies fanatic. He is second in my heart only to dear Alexandre Dumas, with whom, now that I think about it, he has a lot in common, though that probably ought to be a post of its own some day in the future. In Val Ross’s new biography, just as in previous ones, Davies has been held up to the light on such diverse defects of character as racism, misogyny, snobbery and dishonesty. I like to think I Get him and can deflect these criticisms. I certainly don’t buy any one of them (except maybe the snobbery, but I don’t think that’s such a bad thing) and the existence of these claims don’t shed a moment’s doubt on my total love of every word he has ever written.

What I want to talk about now, though, is women in literature.

When writing themselves, women in contemporary literature present to us complex, nuanced, whole people who, nevertheless, tend (in my experience) to be fraught with self-doubt, victimized and rather over-sensitive. A convincing, “true” portrait of a woman is of one riddled with weaknesses to be overcome. That’s all very well, and a hallmark of modern protagonists of both genders. But the world of Robertson Davies is populated by people of a different sort, people who are both at once flamboyant and down-to-earth, people who make decisions and take actions and get involved in incidents. His characters do not moon about (for very long) gazing at their navels, stymied by doubt and deep emotional damage and I don’t think he would have found that portrayal of women very accurate or acceptable. I doubt he would have respected it very much. One of Ross’s interviewees (Arlene Perly Rae, in fact) comments that she felt Davies saw women as the “…Muse and we were the truly creative ones”. But even that observation ignores Davies’s earlier experiences with women and the impressions it made on him.

Davies felt so oppressed by his mother that when she died he stayed up all night genuinely afraid that he was going to die too – that she would kill him and take him with her. Of his maternal grandmother, RD says, “She was spared to a great old age, and as generals have horses shot under them in battle, she outwore two old-maid daughters.” While more modern writers (*coff* D.H. Lawrence) might have wrung this into a Freudian passage of manhood, I think Davies understood this grip as a balancing of power rather than an obstacle to be overcome.

Davies had a good understanding of Power, how it is gotten and how it is used. He clearly respects the power a woman can wield.There is a tradition of young literary men being tormented and smothered by their mothers, mothers who are perceived as having power over life, love, freedom and death. This power over them is not limited, either, to just the mother: grandmothers, ferocious aunts, teachers and in-laws have been depicted similarly. The Formidable Woman is a literary cornerstone, a foil on which the lives of many a young hero turn.

And yet when evaluating the treatment of women in literature, we don’t give any credit to these women and their creators. The softer women, the victims and stumblers of, for example, Fall on Your Knees, Cat’s Eye or Lullabies For Little Criminals are lauded and excused from accusations of misogyny despite, in my opinion, being unflattering portraits of weakness. Stronger, more powerful women populate the novels of Salman Rushdie, V.S. Naipaul, Jane Austen and Charles Dickens and yet are ignored or worse, faulted because the depiction of a woman as the Beast of the Hero’s Journey is considered to be a bad thing.

Maggie Smith as Miss Betsy Trotwood.

I want to beg reconsideration for this position. The power to terrify, to take control and to assert oneself is a wonderful aim for women! One of my favourite women in literature is David Copperfield’s Miss Betsy Trotwood, the (initially) man-hating galleon of no-nonsense wit who has taken her life back and installed herself as the independent master of her own domain. She might not be the hero of the book, and she isn’t rewarded by the author with True Love or Children or any other such sentimental tripe, but she represents what more women should aspire to instead: strength, character and independence. Furthermore, as we later find out Miss Betsy has been victimized in her life – but she does not assume the role of a victim. She steps up to the plate and bulls through. I won’t comment on how hard it was to write that sentence without invoking gendered language (“man up”, “took it like a man”), by the way; suffice to say there’s no reason in literature that it should have been.

Betsy Trotwood is the unfair example – one of the most protagonistic Formidable Woman in literature. But what side of the pro/an tagonist pitch a character falls on should not detract from the respect the author has shown her. Strong, proud women range from Marilla Cuthbert in Anne of Green Gables to Balram’s old granny in Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger and they share the unappreciated role of being able to get their own way and scare the bejesus out of everyone they come across in the meantime.

Robertson Davies was encyclopedic in his knowledge of Victorian literature and dedicated in his defense of it and was surely more than familiar with the Formidable Woman and her place (which is, by the way, at the top of the heap). His description of his rancorous old grandmother as an “old General” is reverent and if he seemed to resist movements towards a change in womens’ roles I don’t think it was from lack of respect. I suggest he saw these shifts as trivial in the balance of real power.

Maybe it’s just me, but I would rather be seen as an “old General” than a “complicated woman”. Right now I’m more of a Lieutenant Junior Grade, but I’m growing; and I hope some day to become the sort of woman who will haunt men long after I have died – and not because they idealized me. Call me power-mad, but if I were a man that kind of lasting impression would be considered kingly.