August 28, 2019

Archipelago, or, How I Became an Accidental Self-Publisher

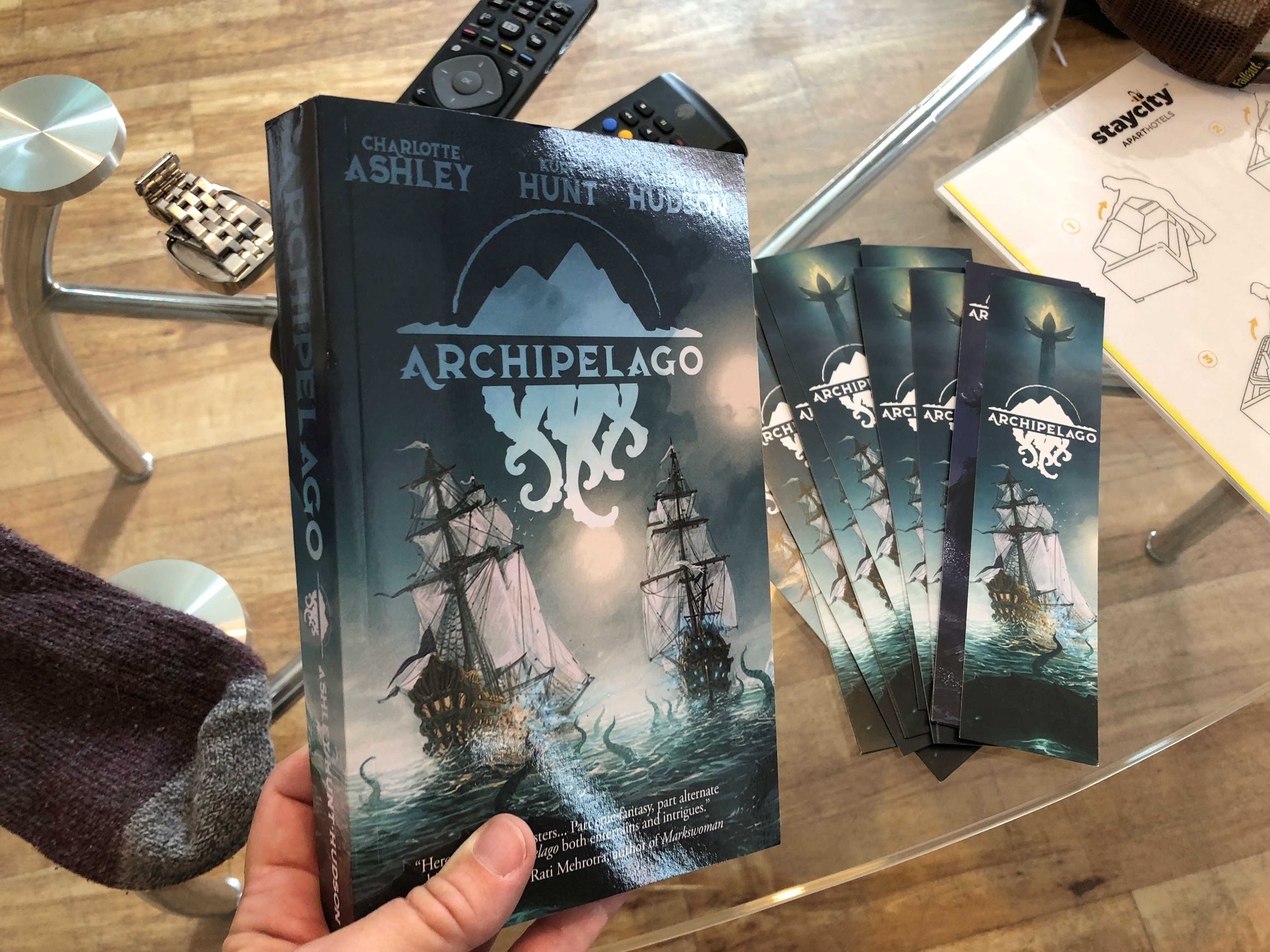

When we launched Archipelago as a Patreon-only project in 2017, we knew we were trying something traditionally nonviable. Patreon was (and is) an iffy lifeline for creators, but Kurt, Andrew and I had creative energy to spare and we wanted to try something new. So, we decided to write a serialized, collaborative, quasi-competitive trio of intertwined novellas. “On the side,” we told ourselves. Just to stretch those writing muscles a bit. (Yah, I know. I see the face you are making.)

The project was, by crowd-funding standards, a success. Not only did all kinds of people subscribe, but the “season” that we wrote was great. In fact, increasingly, my greatest frustration was that this throwaway experiment we had embarked on was better than it had any right to be. I spent a solid year sweating over what would ultimately become quite a long novella with multiple tie-in short stories, and it was paywalled on a difficult platform. I wanted it out.

But Patreon is still “published” and what do you do with three novellas that have already been published?

Archipelago is too good to abandon there. So we did what any self-respecting creative with too much energy does in 2019.5. We took up as indie publishers.

I have not been kind, in the past, about self-publishing.

Being deeply entrenched in the traditional publishing world set me up with a lot of hurdles to accepting self-publishing as a viable career option. I had seen, in the Olden Times, how vanity publishing [didn’t] work, and I could see many of the same pitfalls in new media self-publishing. It makes publishing easy, cheap, and quick, none of which are the hallmarks of quality. Millions of books are published every year, I knew, and reaching an audience is not simply a matter of putting text to screen/paper. Writers, publishers, distributors and booksellers together have to log thousands of hours of work to get a book not just published, but read. Who on earth wants to take that work on alone?!

Well, lots of people. Those of us in the trenches have wisely been calling the practice “indie publishing” for some time now, rather than “self-publishing.” Deciding to go into business as a small press publisher is a hecktonne of work for very little reward, but it is a Noble Cultural Endeavor with credentials ranging back to Gutenberg, so in both senses, that is really more what the current practice is like. Indie publishers are at the center of a huge industry that is keeping an awful lot of us creative types in food & rent: they understand the value of timeless arts such as copyediting, layout design, illustration, and marketing management. They know their craft and pay the bills. And, you know, their books are as good as anything out there.

Yah, I mean, there are still a lot of people out there who think you can bang off a draft, find a cousin who knows their way around Paint, and then upload it to KDP — and I FROWN AT YOU, folks — but this is 2019.5 and I have to finally admit that isn’t what indie publishing is. It hasn’t been for some time.

Well, guess what!

We didn’t want to self publish. Nothing great is created in a vacuum. We did what smart publishers do: we hired the best people we could find to do the best work. From the revisions to the layout to the logo design and cover art, we went over every stage of the publishing process with meticulous care and spared no expense getting the book we wanted in the end. This isn’t a vanity project. We are publishers, and we are professionals. Archipelago is something we wanted to be proud of.

And I am.

We launched the ebook in time for a Dublin WorldCon sale, but if you missed that, we’ve got something even better now. Today, the paperback goes on sale. With every paperback purchase you get the ebook free. Personally, I think the paperback is a thing of beauty but if you are into reading on your pad instead, then WHY NOT BOTH?

Naturally, I’d be thrilled if you bought the book. I would be even more thrilled if you wanted to review the book, on Amazon, Goodreads, your blog or elsewhere. And reach out if you want to talk! I’m eternally available for interviews and guest posts.

I never thought I would self publish. But then, I hadn’t imagined the Archipelago either. Now, I am grateful for both.

November 21, 2017

A Short Note About Book Distribution

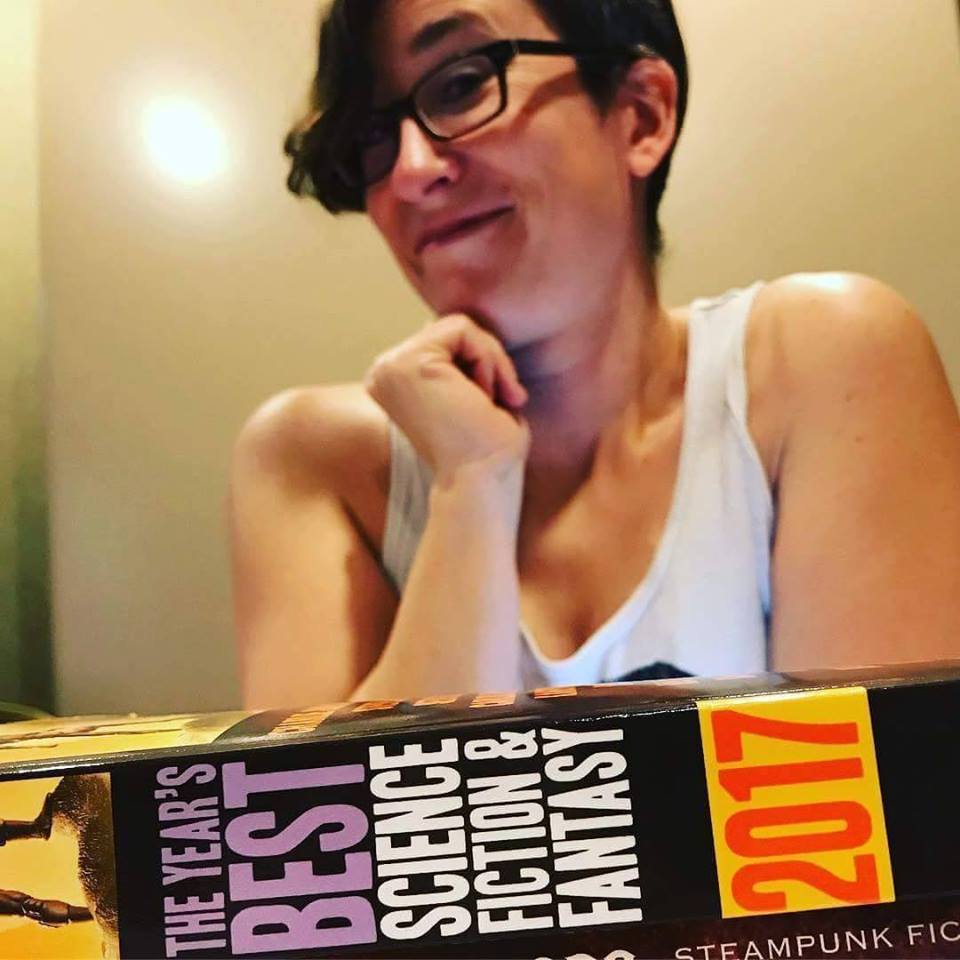

Good news first! The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2017 ed. Rich Horton (Prime Books 2017) is out, and I am in it! My contribution is “A Fine Balance,” originally published in the Nov/Dec 2016 issue of F&SF. I’m over the moon at being included!

Good news first! The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2017 ed. Rich Horton (Prime Books 2017) is out, and I am in it! My contribution is “A Fine Balance,” originally published in the Nov/Dec 2016 issue of F&SF. I’m over the moon at being included!

I… only wish it had been easier to actually get the book.

I work in a bookstore. I can, and do, order anything I like for myself, even under terms and conditions that we might not daily agree to. But this has been the second time this year that a book I appear in has been difficult, if not impossible, for me to bring in.

Last month, I spoke with a number of other writer/booksellers at a panel at Can*Con in Ottawa about how writers can interact with bookstores. Ultimately, it turned into an hour-long lesson on the supply chain, because writers don’t fully understand that getting published does not necessarily mean showing up in stores. Over the month since the con, I have come to realize even publishers do not understand how bookstores order and why they can’t get into stores.

So, I offer this to you: a quick breakdown, highlighting especially how the chain has changed in recent years to cut out smaller booksellers. I’ll borrow a thing or two mentioned by my fellow booksellers, Leah Bobet, Aura Beth Roy, and ‘Nathan Burgoine.

You write a manuscript.

![]()

A publisher (this might be you) turns it into a book.

![]()

The publisher places the book with a distributor.

![]()

The distributor sells the book to stores.

In addition, the distributor takes returns from bookstores, then can sell those books to other stores. The distributor also (often) will warehouse the book for a certain amount of time.

Bookstores like to deal with distributors, not publishers. This is because of the returns clause: most bookstores have the right to return usually 10-15% of their purchases to the distributor. The distributor gives the bookstore a credit when the books are received, and that credit can be spent on other books from that distributor. This means you might return a book from one publisher and spend the credit on a book from another publisher.

This is a credit worth having. It’s flexible. Dealing with each publisher individually would not only be a logistical nightmare, but it means your return credits would be of very limited use. What if that publisher only has one or two books? Nope. Consolidating through a distributor encourages bookstores to take risks on books and buy things from micropresses, because they aren’t trapped in a relationship with that one book.

From the publisher perspective, having a distributor allows them to mitigate the loss from returns, because those books stay in the distributor’s system longer, and can be re-sold to other stores. It allows them to get into bookstores all over the country/world, using that distributor’s infrastructure. It saves enormously on administrative nonsense. It opens the door into thousands of bookstores.

I understand publishers take a hit from this chain in two ways: one, the distributor takes a cut. They just do. That’s their price. Two, the distributor almost always allows returns from bookstores and thus, books will be returned, ultimately, to the publisher.

Nobody likes returns, but they are a fact of life in almost all retail. Every year, millions of new books are published. The bookstore buys them for roughly 40% off of cover price – meaning for every 2 new books we want to buy, we need to have sold 3 other books at full price. For every 2 books you see on the shelf, 3 other books had to be sold to pay for them. To say nothing of rent, labour, and operating costs. That’s a HUGE volume, and it never happens. If we had to wait to sell three book in order to buy two more, we would literally never buy new books. We’d just be sitting around waiting to move old, outdated stock.

Returns help. You send back last year’s fashions to make room for this year’s. Thus, the world goes around.

Some distributors have found a way to attract the business of nervous small publishers by offering that holy grail: NO RETURNS. Diamond Distribution, who specialize mainly in comic books, are the biggest of these. This is who distributes for Prime Books – the publishers of my Year’s Best.

How do they do this? Well, they put the burden on the bookseller. In order to be allowed to order from Diamond, the bookseller needs to buy a minimum number of their books – which, again, are mostly comics and small presses. This minimum order gives you the right to a very limited discount (less than 40%) and no returns. If you want to be able to return books, your minimum order needs to be even higher. Returns only apply to new books – not backlist – and they need to be sent back quickly. They don’t have any shelf life.

How do they do this? Well, they put the burden on the bookseller. In order to be allowed to order from Diamond, the bookseller needs to buy a minimum number of their books – which, again, are mostly comics and small presses. This minimum order gives you the right to a very limited discount (less than 40%) and no returns. If you want to be able to return books, your minimum order needs to be even higher. Returns only apply to new books – not backlist – and they need to be sent back quickly. They don’t have any shelf life.

This is a model built for comic distribution, where new issues come and go monthly. For books – and graphic novels – it is totally non-functional. For this reason, most big comic book publishers have left Diamond and gone to more conventional distributors.

These days, I only find myself face to face with Diamond if I am dealing with a small press. These guys are usually just inexperienced. They were burned once by a high return, and they are determined it will never happen again, so they go with the big name that won’t give their books back.

But their books will never reach bookstores. Very, very few independents can afford to open an account with Diamond, much less a big enough account to get the terms they need. Diamond is a graveyard for small presses.

This brings us to Ingram. Ingram is the Amazon of distributors: a huge, sprawling mess of every book ever, with no customer service and very rigid terms. Almost everyone lists with Ingram because they might as well. Ingram will allow you to list your books as non-returnable, if you need to. They means, of course, they won’t warehouse them, and they may not offer the bookstores a discount. The bookstore can technically get the book, but they aren’t encouraged to. Aside from lack of returns and bad discounts, Ingram doesn’t offer any useful cataloguing service, they have no customer service, and their shipping fees suck.

I did, after all, order my Year’s Bests from Ingram. They were printed on demand and are, thus, miscut. There was no discount, and they were shipped to Canada at a great cost to us. Even at my “wholesale” cost, they cost me 50% more than cover price.

I was going to put them on the shelf and sell them, but I can’t. Not looking like that. Not at those rates.

So, what does a writer or publisher do, if they want their books easily available in bookstores?

Writers, ask prospective publishers who they distribute their books through. If the answer is “direct,” run. You might as well print your own book.

If they only distribute through Diamond or Ingram, know that this means your books will not show up in indies. They may not even show up at your local B&N or Chapters.

There are lots of good, reputable distributors in both Canada and the US. There are the big guys, of course: the distribution arms of Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group. I give Perseus distribution a tentative thumbs up, though they have recently been bought up by Ingram and have become very difficult to deal with, even though they operate separately from Ingram.

There are also excellent small press distributors who understand very well the challenges small presses face. Independent Press Group (IPG) and National Book Network do great work. In Canada, we have Literary Press Group (LPG), LitDistCo, Raincoast Books, Brunswick Books, and UTP Book Distribution. There are more, many distributing in particular types of books (university presses, scholarly publishing, children’s books, etc.) Do some research. Ask your local bookseller what they think of your choices.

Publishers, one last thing about returns.

Returns suck. I get it. Especially if the book store chain you are working with doesn’t even give the books back – some will just pulp the books and then bill you for them. But there are ways you can work this into your contracts or publishing model.

DON’T REPRINT RIGHT AWAY. Initial sales are ALWAYS inflated. Wait until the three month mark, when returns start coming back. Obviously, use your professional judgement: if your book was Tweeted out by Obama or up for a major award, REPRINT FOR SURE. But if Indigo just happens to be using it as a doorstop in all its stores, maybe wait. Give it a minute.

ASK FOR YOUR BOOKS BACK. Pulping is not in any way the industry standard. Your distributor can ensure that your books come back to you in salable condition. Take these on book tours with you.

OFFER FLEXIBLE DISCOUNTS. This is especially applicable if your distributor works with a discounter for overstock books. Got lots leftover? High returns? Offer them out for a bigger discount. Sell ’em to a discounter in bulk. The book chain is many-faceted, and your business plan has to account for the different stages of a book’s life. You might lose money at some of these discounts, but that is made up for with the better sales you get on front list by being out there with books easily available.

*

Now, it’s possible that this is indicative of a seismic shift in the industry. Diamond and Ingram are perfectly sufficient for dealing with Amazon. If most of your sales are through Amazon, then maybe it’s worth cutting out booksellers in order to get risk-free distribution.

I think this is narrow thinking. Booksellers are your army. They are your boots on the ground. Even if readers increasingly buy their books online, they still visit bookstores to browse, to talk to the staff. They want to see what’s out there, connect with people who love what they do. A bookseller is worth a ZILLION Amazon algorithms. Worth at least ten book bloggers, in my humble opinion, because we are steeped in this stuff. You want us to champion your books. You want us to put it in the hands of your readers.

Open floor, here. Any questions? I’m happy to field any technical book chain or publishing questions here. Pick my brain. That’s what booksellers are for. If you appreciate this post (and others like it,) click below to tip!

February 8, 2016

Apologies to Clockwork Canada

I’m here to fess up. I have been a tremendously terrible person.

Last month, I went to a launch of Exile Editions’ latest anthology, Playground of Lost Toys (ed. Colleen Anderson & Ursula Pflug.) I didn’t really want to go. Lost Toys? I imagined an anthology of creepy dolly stories. And who were those editors, anyway? I went to the launch because I had friends in the anthology – sorry guys – that’s it.

I should have known better.

I’ve been familiar with Exile as a Canadian publisher for years, but up until a few years ago, I’d thought of them as a literary small press. They published Morley Callaghan and George Elliott Clarke; Leon Rooke and Daniel David Moses. Good ‘ol Canadian Literature. Not, frankly, my hat, but stuff we dutifully stocked at the store.

Then, out of nowhere, they published Dead North, an anthology of Canadian zombie stories. I thought this was super-weird, coming from Exile, but the cover art was so good that I overcame my boredom with zombies and bought it. I was pleasantly surprised: Dead North was a solid mix of literary and speculative fiction, zombie stories that did more work than just being gory thrill-rides. Then came Fractured, stories of the Canadian post-apocalypse. Another subject I thought had been done to death, but Dead North was good enough that I opted to give the creative team a chance. Fractured was another very solid book, managing to present original, literary work despite the well-trod path it started on.

Then came Playground, and, like I said, I thought the subject was silly. Despite loving the previous two anthologies, I let my prejudice rule my head. Toys are dumb! It’s probably all going to be horror, anyway. The publisher obviously doesn’t know anything about speculative fiction! Rawr, I am a jerk!

Well, the launch was amazing, for starters. Six readers, great stories, and one impromptu Bowie serenade. The food was good, there was beer, and my friends were there. I bought the book to be generous, but I read through it in two days. Fully half the stories made me laugh out loud, and I am a tough customer. The book was great. It looked so stupid (again, sorry) but it was great.

I learned my lesson, right? Ha ha! Ha! Ha.

I learned my lesson, right? Ha ha! Ha! Ha.

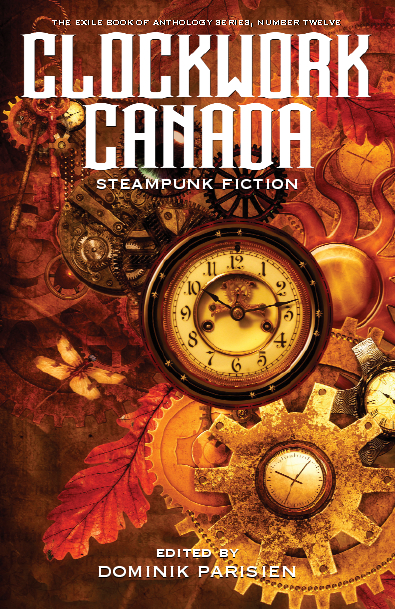

About a year ago, Exile put out a call for their next anthology: Clockwork Canada. Yep, Steampunk. And – you’d think I would know better by now – I rolled my eyes. Like, Steampunk, guys. Doesn’t Exile know this has been done to death? I know, I am the worst. Not a generous bone in my body. Only after I spoke with the editor, Dominik Parisien, did I even consider submitting, because he assured me they were looking for “Canadian alternative history of all kinds,” not just your usual airship stories. Yah, after four amazing anthologies, I still needed a tête-à-tête with the editor to convince me to even think about it.

Oh my God, am I ever glad I did. Dominik bought my offering, “La Clochemar” (no doubt because he had no idea what an asshole I had been about the whole Exile project,) and Exile managed to get us this ridiculously beautiful cover (right.) I am alongside some absolutely brilliant writers inside – writers who were probably far less diva about the whole thing than I was. All in all, the book seems set up to be another brilliant addition to what has been a brilliant series of speculative/lit short story anthologies. I… well, I am very excited.

Exile, Dominik – I am so, so sorry. You’ve never let me down! And look, people – here’s my pitch: we won’t let you down either. This is gonna be great.

You can pre-order Clockwork Canada now! It’s slated for release in early May 2016. Available from:

You can also drop us a note at our Goodreads page.

(Sorry!)

January 13, 2015

Hug a Critic (Or Nominate them for an Award)

A lot of ink has been spilled, by me as much as anyone, about the genre ghetto. The mainstream publishing industry pointedly ignores genre in all those spaces it considers respectable, like newspaper reviews, literary awards, and adult conversations. Meanwhile, genre fandom often resists analysis and criticism from mainstream culture, insisting that their corner of literature has its own rules and standards that a “non-fan” can’t understand merely by reading a genre book. There are a lot of shots lobbed about high culture and low, the people versus the establishment, fans versus experts.

And yet there is more self-aware crossover now between literary fiction and genre fiction than there has ever been, in the short fiction markets in particular. The golden age of pulps might have passed on, but in its place is an incredibly fecund culture of online literary ‘zines with expressly speculative mandates. When I stopped reading fantasy fiction fifteen years ago, we were still in the age of Locus, Asimov’s, and Realms of Fantasy. When I returned a couple of years ago, most of these glossies were dead, but the internet was teeming with stranger things, more experimental things. The internet had this effect on everybody over that fifteen-year period: anybody can publish anything, so they do. Fringe projects abound, but there’s a difference in SpecFic:

It pays.

Literary SpecFic isn’t the fringe. It’s an increasingly sustainable share of the short fiction market with a demanding, critical audience willing to pay for the product. In no small part because of the precedent set by the pay rates of the old pulps (and the writer’s unions that sprang up around them,) literary short fiction markets with genre flavours now pay more and more reliably than most “mainstream” literary markets, a distinction you can see in the talent they attract. (These inroads have been less marked in novel-length works: there, a literary SpecFic work is still likely to be marketed and branded as “literary”, downplaying the genre aspects of the work.)

The overtly hybrid form is being led by short fiction. SpecFic short fiction is good. It is important. And it is all but invisible to the mainstream.

A year ago, there was a lot of talk on Twitter about a need for more serious criticism of this fiction. Not only is there more material being released than your average reader can sort through, but much of it is complex material that benefits from a close read. Critics help to sort and decode, to lead the conversation.

There were (and are) some phenomenal critical sources, like Strange Horizons and The Cascadia Subduction Zone, but these focused primarily on full-length works, including anthologies. Other places – Tangent Online, Fantasy Literature, and Locus Online – covered short fiction in brief; overviews without much analysis. There was a need for regular, ongoing, critical coverage of the wealth of material coming out of the periodicals.

As it turns out, there was a need for a lot of regular, ongoing critical coverage of this material. Once the spores took root, short fiction review columns popped up like mushrooms in October. I like to think of 2014 as the beginning of a new critical era in genre fiction. Now we have Amal El-Mohtar’s Rich and Strange up at Tor.com, K. Tempest Bradford covers short fiction at io9. Fantastic Stories of the Imagination has Gillian Daniels and just a couple of months ago, Nerds of a Feather started a “Taster’s Guide” to a flight of interesting short fiction each month.

And, of course, I have maintained Clavis Aurea now for over a year.

In a recent Twitter discussion about award eligibility, Niall Harrison (Strange Horizon‘s editorial force) pointed out that while critics are technically eligible for the Hugo Awards’ Best Fan Writer, “…it’s a poor fit and almost never happens.” Individual essays occasionally get nods (such as last year’s winner, “We Have Always Fought” by Kameron Hurley,) but it is hard to define a critic’s body of work as a whole. You could perhaps nominate their blog or a single, standout column. Critics have not, historically, had their own brands the same way fiction writers do.

I believe this year is different. The same ‘zines who have raised the bar for quality SpecFic short fiction are housing and branding critics with definable, nominate-able bodies of critical work.

I would love to see this trend recognized in this year’s awards season. Literary criticism in genre isn’t new, but it is newly normalized. There is a new critical culture. We’re showing that genre isn’t a ghetto: it’s a metropolis.

You are eligible to nominate for the 2015 Hugo Awards if you were a member of Loncon 3, a member of Sasquan, or the 2016 Worldcon, MidAmericon 2. The nomination period opens January 31, 2015. You will be able to nominate up to five people or works in each category.

Critics and their works are generally eligible for both Best Fan Writer and Best Related Work. You could nominate the critic (say, Amal El-Mohtar) as Fan Writer, and their column or blog (say, Rich and Strange) for Best Related Work.

Let me rephrase that. You should nominate a critic for Best Fan Writer, and their body of work for Best Related Work. I hope very much that you will consider nominating me and my column, Clavis Aurea.

Critics are a vital part of the literary landscape and they work hard. As literary SpecFic continues to push boundaries, reach new audiences, and gain new respectability, these critics will have had no small part in the shaping of the genre. That’s a role that deserves to be recognized on the ballot.

Hug a critic!

***

Next week, I’ll be laying out my own choices for the categories I intend to nominate in! Stay tuned!

November 19, 2014

How I Became an Editor – the PSG Story

In the brave new world of the self-publish wild, it is becoming more and more common for people who know nothing – and I mean nothing – about publishing to find themselves in the position of being full-time publishers. It is also perfectly possible for someone to publish a very good book without learning anything about publishing along the way. This is why, mid-summer 2013, I took on the role of editing PSG Publishing‘s first short story anthology, Library of Dreams.

In the brave new world of the self-publish wild, it is becoming more and more common for people who know nothing – and I mean nothing – about publishing to find themselves in the position of being full-time publishers. It is also perfectly possible for someone to publish a very good book without learning anything about publishing along the way. This is why, mid-summer 2013, I took on the role of editing PSG Publishing‘s first short story anthology, Library of Dreams.

I’m an editor, I thought. I have been fixing people’s grammar and spotting typos for, like, ten years! No problem, I thought. No problem.

I don’t know how it had previously escaped my notice that an anthology editor and a copy editor have two very different jobs, but it had. It took some time for the reality of what I had agreed to do to dawn on me. And it didn’t so much “dawn”, gradually over time like the rising sun, as it swamped me, like a flash-flood.

PSG’s project leads chose a theme and a charity, and I put together submission guidelines. Stories began to trickle in, manageably at first. Many of the writers were going through the submissions process for the first time, so I fielded questions and lend encouragement. Maya Starling put together a book cover that was so slick, we instantly looked more professional than publishers who’ve been in the game for years. Things were quiet and under control until the end of the summer.

Then came the deadline. I had 14 stories, but not all of them were ready to go to print. There were revisions to make, content to clarify, changes to finalize. Some of the newer writers had never used Track Changes, nor done a substantial revision. In one case, I asked for a revision and got an entirely different story back. One writer pulled out at the last minute. One still hasn’t submitted his contract. I gave us all the month to get the stories ready to be copy-edited. We missed my deadline by two weeks.

By the fall of 2013 I had coached, copy-edited, revised, and copy-edited again 14 stories and my job had only just begun. Sink or swim, self.

I swam.

I learned enough legalese to write contracts. I picked fonts and dingbats. I agonized over what order to put the stories in, laid it all out in rough, and then changed my mind about everything. I signed a contract with LitWorld and applied for an ITIN – an American tax ID. Maya did all the heavy lifting of formatting the book for Createspace, Kindle and Smashwords, but then we had to proofread all three editions again – twice.

By the time we released the book on December 15th, 2013, I had been working on it full-time for three months. And it was worth every. Single. Minute. Library of Dreams is clean, beautiful, and best of all – good reading.

When PSG fielded the idea of doing a second anthology this year, I jumped at it. I had the skill-set now – I was an editor. Not just the kind that fixes your spelling – the other kind. An Editor.

When PSG fielded the idea of doing a second anthology this year, I jumped at it. I had the skill-set now – I was an editor. Not just the kind that fixes your spelling – the other kind. An Editor.

If last year was a flash flood that nearly drowned me, this year was a trans-Atlantic swim for which I was trained and fit. Oh, it was hard. Everybody at PSG – especially Maya Starling, Yzabel Ginsberg, Ang Thomas, Tim McFarlane, Kim Fry, Laura Perry, and ALL our authors – worked their butts off to get the book together in a way we could all be proud of. But we were ready this time and I think it shows.

Chamber of Music launched on Friday, November 14th 2014 – a full month earlier than last year – and is now available in paperback and ebook from Amazon, Smashwords, and a host of other online sources. Proceeds from its sales will be donated to Musicians Without Borders. I hope you’ll have a look!

May 28, 2014

In Which I Invent Numbers

Last night I read Hugh Howey’s take on the whole Amazon vs Hachette thing. I don’t know why. I knew it would make me mad, and it did. Howey is, by all accounts, a super nice guy who is always available for emerging writers to pick his brain. He supports the community and tries his damnedest to make sure creators are not getting screwed. So I had to think that, rather than trying to shill for The Man, he must just be incredibly stupid and ignorant. I was up half the night seething bitterly about how many customers I would face tomorrow who felt entitled to have temper tantrums at the cash register because we/publishers are unfairly getting rich off their backs, and why can’t we all just discount books like that great Saviour of the People, Amazon???

Except Howey isn’t stupid and he knows how publishing works. So what was up with his backward-ass approach to explaining how publishers arrive at their prices?

Then it hit me. Howey is thinking like a self publisher. He thinks Hachette is a self publisher.

When you self publish, the money you spend up front to produce the book is a gamble. It’s the cost of having a dream fulfilled, or of getting your foot in the door. It’s a “long term investment”, betting on the day, five books down the road, when you really start to take off. Nine times out of ten, you never see that money again.

A publisher does not gamble any more than it has to. It looks at its costs – editors, designers, publicists, customer service reps, distributors, warehouses, printers, lawyers, mistakes, everything – and works out exactly how many books they need to sell at what cost in order to make it back. Some years a book hits big, and in those years, somebody makes bank. But most of the time, they pay their employees and produce books.

Howey’s assertion that Hachette “get[s] the full wholesale price of $8.99,” only makes sense if you think Hachette is a guy, like Howey. When a self-publisher sells a book, they use that money to pay back the loan they made to themselves during that book’s production – a cost that Howey seems to be counting after profits, the same way one might buy groceries or pay the hydro bill. Publishers do this the other way around. The wholesale cost of the book pays for the cost to produce the book. You only look at profits after everyone has been paid.

If a self-publisher never makes their money back, they may decline to self-publish again. If they were publishers, this would be called “going out of business”. Hachette isn’t super-keen to do this.

![]()

But let’s back up a bit. Let’s talk about Hachette’s “crazy” ebook prices, now that we understand that they are not gambling the same way a self-publisher might.

What does it cost to make a book? What % is the author really getting?

Here’s a simplified break down of the cost to self publish. Back-of-the-napkin stuff.

Book cover – $150 – $200 (this is cheap. CHEAP. You can do it for less, and we will be able to tell.)

Editing services – $400 (this is also cheap, but this is what I will charge you for an 80,000 word novel)

ISBN/expanded distribution – $99 (this is to get an ISBN you can use outside of Amazon)

Copyright registration – $85 (your work is automatically copyrighted, but many people choose to register for ease of legal protection. Many.)

Layout & Design – $150

Kirkus Review (this is a handy stand in for “publicity costs”)- $425

A website – $600

TOTAL – ~ $1900

This was done on the cheap. You could do it even cheaper, true, but you will pay instead with your time, sanity, and quality of product. So, your mileage may vary, but this is a handy number.

The million dollar question is, how many copies will you sell? Truly, nobody knows. Here are some things I do know:

90% of books registered with BookNet Canada only sell one copy. One. Copy.

Tobias Buckell dissected some Smashwords data last year that shows the vast, vast majority of titles sell fewer than 100 copies.

The best-selling anthology I have ever contributed to has sold 141 copies.

Award-winning YA author Arthur Slade reports selling an average of 635 books per title over a whole year, but this is 4780 copies of one best-seller and an average of 175 books for each other title.

But, that said, I know a lot of first-time self published authors of romance & teen books that come off Wattpad with “fan bases” of 5k+ followers. They expect to sell 500 copies in the first few months, and they do that or better. So if you have an established author presence and a book with a known audience, 500 is a good number to shoot for.

Let’s say you’ll sell 500 copies because I am being very generous.

You price your ebook at $5.99 because that’s what Hugh Howey did. You sold 500 copies. That’s nearly $3000.

Amazon takes 30% ($900)

The IRS takes 30% ($630)

You made $1470. Congrats!

Wait, sorry. I mean you are still short $430.

![]()

What about Hachette? How does this break down for them? Let’s look at one subsidiary, Orbit books.

I don’t know how many employees Orbit has, but let’s say you only need the ones that cover the same services the self-publisher paid out for themselves – even though they also need laywers, customer service reps, account managers and so on. Orbit publishes roughly 60 books a year, so we will assume a book gets 1/60th of their services (though in reality, things aren’t this fair – still, short hand). Salaries extrapolated from the bottom end of Indeed.com’s salary estimator.

Cover designer – $48,000/60 = $800

Editor – $47,000/60 = $784

ISBN = $5.75 (you can buy them in blocks for much less than they sell individually)

Copyright registration – $85

Layout & Design/Typography – $58,000/60 = $967

Publicity – $44,000/60 = $734

Printing – $3.90/book x 500 copies = $1950

Author Advance – $5000

Website – $0 (the publisher probably won’t do this for you!)

TOTAL – $10,325

Well, we printed 500 print copies. Let’s say we will sell these in addition to 500 ebooks, because I’m going to pretend I don’t know full well that plenty of big-5 titles only sell 150 copies, period. Let’s say Orbit has high hopes for you, and you will sell 1000 books.

If Orbit sold them for Howey’s $5.99, they’d have $5,990. Amazon would take 30% = $1790. I can’t guess at Orbit’s tax rate, but let’s be generous and say it’s 30% too. $1260. The distributor, by the way, wants 10% on the 500 print books you sold through them. That’s $300. Well, so far Orbit has lost almost $7000 on this book.

If MSRP was $8.99? $8990, and Amazon’s already paid. Well, we’re closer. They’ve only lost $4000. Incidentally, if they don’t pay the author an advance and just give them “25%” as Howey suggests, the author “only” gets $2250, but Orbit has only lost maybe $400. Another few months and they might break even.

Hachette’s barely eking by at $8.99 MSRP, and the author is $2250 ahead instead of $430 behind.

![]()

Everybody thinks they will do better. You can make this look better for Amazon & the author by selling more units. In scenario one, you will break even after you’ve sold another roughly 150 books. You’ll make the same as you might have in the Hachette scenario 760 books after that – so in order to make the same money on 1000 traditionally published books at $8.99 MSRP ($14.99 on Amazon), you’ll have to sell 1400 self published ones at $5.99. Maybe you think you will make those sales. I feel that this is… optimistic of you, but that’s your business. It is your dream to gamble on. You might, after all, make it big, like Hugh Howey.

But it would be business insanity for a mainstream publisher to operate as if they are guaranteed 1400, or even 500, sales of every book they publish. They know very well they have to balance the misses with the hits. They have been doing this for decades, after all.

And, of course, there’s the pesky issue of the salaries listed there. It costs more for a publisher to make a book because it employs people – real humans making middle-class salaries. We should not begrudge those people their jobs. Hell, most of them are probably the same creators Howey defends. The $2200 you might make self-publishing a book is not going to pay your bills, not unless you can write a novel every three weeks. Even being a freelance designer or editor isn’t going to pay your bills – not unless you are extraordinarily successful – or you put your prices up. I don’t edit six 80,000-novels per month, let me tell you.

No, it’s publishing that supports the entire creative industry. That’s where book lovers find jobs. Is that worth a buck per book to you? Is it to me.

March 28, 2014

On the Economics of Creative Industries

Yesterday, Ontario’s major news outlets reported that the provincial government was finally starting to crack down on illegal unpaid internships, starting with a blitz, apparently, of the magazine industry. The reactions from the left shocked me. Progressive people who should have known better bemoaned the death of these “great opportunities” and wondered where new graduates were supposed to get “valuable work experience” now.

So a completely voluntary arrangement that worked for both sides is now illegal. Great work, government of Ontario!

— Andrew Coyne (@acoyne) March 27, 2014

I undulated between frothing anger and silent shock all afternoon. From… jobs, maybe? The paying kind? How did we manage to swallow, hook line and sinker, the idea that the first step into the workforce should be unpaid?

We probably swallow it because we of the creative-dependent industries work deep in the belly of starving artist territory. Not only are we told day in and day out that we cannot make a living at our art, but we’re chastised for having entered Humanities programs in the first place, then shamed if we consider “soul-destroying” paid work over pursuing our art. Writers are told not to quit their day jobs, cartoonists give their product away for decades before managing a single successful Kickstarter campaign, and we pay thousands upon thousands of dollars for skill-developing workshops.

Of course we expect people to work for free. An internship, after all, is about education, and we have agreed as a society to pay tens of thousands of dollars a head for those, endlessly, forever. Rational, kind people continue to argue this morning that as long as you’re learning something at your unpaid “internship”, they should be legal.

@jaredbland It’s such a narrow view of education to say an internship can’t be educational unless associated with a university.

— Nick Mount (@profnickmount) March 27, 2014

So why stop there? What separates a “job” from a “learning opportunity” anyway? Especially in the creative fields, where we’re offered jobs for “exposure” and “experience” every day? Or academia, where you publish relentlessly for no compensation whatsoever except a vague CV-padding? You learn something at every good job – why pay anybody for anything?

To further muddy the pool, almost everyone who is associated in any way with the publishing industry works for free once in a while. I read slush for free. The only people who get paid at a place like Taddle Creek are the writers. Rose Fox recently argued that editors need to start asking for a piece of the pie. They correctly point out that “money isn’t thick on the ground” in the industry, but we have to draw the line somewhere.

If the only people who can break into an industry are the people affluent enough to work for free for years at a time, you’re going to get an industry entirely staffed by white, middle+ class, single young people. Diversity and representation you can throw right out the window, because most people don’t have rich parents, savings, supportive, well-employed partners, or 28-hours available to them in a day. You also help contribute to false economics when you fail to factor in all the labour that goes in to your product. Every literary product I have backed on Kickstarter recently has completely glossed over the editorial costs of their book. $5000 will get you ten stories, cover art, printing and shipping costs, and that’s it. The editors, layout designers, promoters and marketers? You’re volunteers. You’re unpaid interns.

We work for free because we want these products to be made, to be available. Given the choice between volunteering to edit something for free and seeing the project die in development, we choose the labour of love every time.

But listen, broadly applied, this is a false dichotomy. The publishing industry is worth billions. If the editors, authors, designers and publicists aren’t being paid, who is? When St. Joseph Media eliminates 20-30 unpaid internships and blames the government, they are being incredibly disingenuous. The Gagliano family who run St. Joseph Communications do very well indeed. CEO Tony Gagliano has donated millions of dollars to cultural projects throughout the GTA – and good for him – he can find $750,000 to pay 30 interns minimum wage.

The money is out there, but we’re never going to see it if we don’t start putting our labour back into the equation. After all, the more of us that are being paid, the more we can pay back. Hey writers – you know you can claim magazine subscriptions as a business expense, right? Do that. Pay in. Demand it pay out.