April 20, 2009

Abebooks as Bibliographical Tool

I recently had to compile a largish descriptive bibliography of my Alexandre Dumas collection and, being library-disabled due to having a new baby around, was a little short on bibliographical resources. The best books (Frank Wild Reed’s Bibliography of Alexandre Dumas, say) were rare and not the sort of things I could check out and take home. Shamefully, I wound up leaning heavily on abebooks.com instead. I felt that this was a bit like using Wikipedia for a history paper.

So imagine my great surprise when Nicholas Basbanes, that book collecting czar, referred to using abebooks.com as doing “due diligence” in his most recent blog post. He admits he has “more work to do” but nevertheless I was shocked that a collector (and academic) of his profile would turn to what is essentially the eBay of books to get a gist of his book’s bibliography. It made me wonder if I should reconsider abebooks’s legitimacy as a research tool.

Abebooks has a lot of things going for it. Almost every rare and used book seller ever lists at least a portion of their stock there. So while there is a real wild west of Dudes Selling Books Out Of Their Garage going on, some of the world’s most respectable booksellers also have a presence. A search might yield 150 results, but at least a few of those ought to be from reputable sellers whose research you can trust. The star rating system gives you an idea of who is reputable and who might not be, just as on eBay. You can certainly find the basics of your book on Abebooks: publication date, publisher, edition and binding. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a blurb of what the book is and why it is important.

But is that any use to anyone? I use Abebooks in order to identify books I already posses and to get inspiration as I rewrite my essay for the final draft. So the book is already in front of me – I already know the publisher and binding, and often the date and edition. What I am looking for is to contextualize my edition, to learn what editions came before and after, what might be unique to my edition, or the history of my edition. This information might be in a listing, but more often it isn’t. Further, there’s no guarantee that the information that is listed is correct. And worst, I suspect many sellers also use Abebooks to do their research, and so bad information tends to perpetuate itself as it is copied from listing to listing. Unlike Wikipedia, nobody corrects Abebooks listings. It is more like eBay in this regard -buyer beware.

It’s true that the quality of an Abebooks listing goes up with the price of the book. Someone hoping to sell a $25,000 book is going to be meticulous in their bibliographical description. Does that mean reliability increases with price? In my experience, absolutely not. Here are a couple example from my experience over the last year or so:

“Due diligence” in the case of this book meant “should I let my daughter chew on this”. The Angry Moon by William Sleator is a beautiful children’s book, and mine is in great condition for a book that has been on a shelf for forty years. What does Abebooks tell me? Well, at the bottom end of the spectrum we have the following description from a five-star seller:

“Due diligence” in the case of this book meant “should I let my daughter chew on this”. The Angry Moon by William Sleator is a beautiful children’s book, and mine is in great condition for a book that has been on a shelf for forty years. What does Abebooks tell me? Well, at the bottom end of the spectrum we have the following description from a five-star seller:

Little Brown & Co (Juv Pap). Book Condition: Used – Acceptable. Former Library book. Shows definite wear, and perhaps considerable marking on inside. Price: US$ 42.65

No date or indication if this is the 1st edition. No real information, and what does “perhaps considerable marking on inside” mean? Is there or isn’t there considerable marking? That strikes me as being a really important point.

On the upper end of the scale we have the following:

Little Brown & Co. an Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Boston, 1970. Hardcover. Book Condition: Cover okay, contents good. Stated First Edition. Oversized. 45 pp, Blue hardcover. Pages clean & tight. Cover has a few stains, wear to corners (cardboard showing), slightly loose, but all pages sturdy. Though the cover is as described, the pages appear unread. From the copyright page: The original legend which suggested this story was first recorded by Dr. John R. Swanton in Bulletin 39 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Tllingit Myths and Texts (1909). The illustrations are elaborations on original Tlingit motifs. Price: US$ 260.00

Now we know the date and edition, and a description of the book’s physical dimensions as well as its contents. But here’s an interesting thing: “Stated First Edition” means that the book says it is first edition, but the seller isn’t willing to flat out declare the book the a first edition. Publishers have been known to not omit the “First Edition” identification in subsequent editions or printings. In this book? Who knows? Nobody has bothered to find out if they’ve got a first edition for sure, despite the much higher price tag.

But this is still an inexpensive book. Here’s another, pricier example.

Le Vicomte de Bargelonne, Alexandre Dumas – Dufour et Mulat, Paris, 1851 Two quarto volumes (268 x 176 mm), havana half-roan, smooth spine tooled, red shagreen-cloth covers (contemporary binding). First illustrated edition, rare, with 58 engraved plates, including 2 steel-engraved frontispieces, by Philippoteaux and J. David. Price: US$ 3489.20

Sounds alright – right? Well, hard to say. The listing confuses me. What constitutes the “first illustrated edition” of this work is still up for debate – two 1851 editions exist (according to Frank Wild Reed, anyway), a Mulat et Boulanger with 58 engravings, and a Dufour et Mulat with 60 plates (35 in the first volume and 25 in the second). Which is this? The Darfour and Mulat ought to have 60, not 58 engravings, so is this the Mulat et Boulanger? For $3,500 I’d really like to know.

Of course, we all know that the internet makes a bad research tool, right? It’s just a shortcut, somewhere to get a starting-off point before we head in to a library. Yah, we all know. But I think it bears repeating again. The internet has a lot of content and some of it good, but we’re still not at that place where it replaces the old books.

April 3, 2009

The 15th Annual The Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book (Also, a tangent)

Wednesday night the Friends of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library hosted the 15th Annual Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book. This year’s lecturer was Professor J. Edward “Ted” Chamberlin and his topic was “If you are ignorant, books cannot laugh at you”, Sir John Lubbock’s Hundred Books.

Lubbock (1834-1913) was known in his time for many things, being a naturalist, the father of pre-historic archeology, the founder of “bank holidays” and a long-time member of British parliament. He was also a tireless supporter of educational rights, and as part of an ongoing effort to encourage the general public to better themselves he published The Pleasures of Life in 1887. This publication contained a list of 100 books which Lubbock felt everybody should read, a list which was transformed to reality by George Routledge & Sons who published all 100 of the books in cheap, manageable editions.

Sir John Lubbock

The somewhat odd title of the lecture was taken from the inaugural address Lubbock gave upon being appointed Principal of the Working Man’s College in 1866. I wish I could find the text of the address, which Chamberlin quoted at length, but I can’t; instead you’ll have to settle for the gist of it. Lubbock believed that reading books provided the best education a person (he was a staunch believer that women ought to be as well-educated as men) could get, since books didn’t correct, bully, preach or judge. Even if you are ignorant, he said, books will not laugh at you. He wanted books made available to all people of every stripe in order that they could encounter and examine them as equals.

You can find the list of Lubbock’s hundred books here. It’s a really fascinating list for its time, including a lot of non-European works like the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Shahnameh, the Qu’ran, the Shih Ching and more. The criteria for Lubbock’s list was that the book should be “satisfying and nourishing”, and ought to bring the reader pleasure. He asked many of his literate friends and eminent literati of the age to recommend what books they would like to include, and he went with a list populated by those books that got the most “votes”.

But he didn’t go with those books alone. The inclusion of many of the older and stranger works was justified because of the “time tested admiration” of hundreds of millions of readers over the years. The list was of good books, but also of popular books. For Lubbock, the most important quality of a book is that it instills a sense of wonder in the reader, and encourages them to dream.

Chamberlin’s entertaining biography painted Lubbock as a man who cared deeply for the problems facing the working class, but he was careful not to dismiss Lubbock’s literary contributions as simply populist. Now, as then (and maybe the fact that we share this sentiment with Victorians ought to tell us something), there is an attitude that Literature and Popularity are necessarily at odds, that being pleasurable is fun and an alright diversion for some (common) people, but Serious Intellectuals are wasting their time reading anything that doesn’t make them suffer. Zoe Heller was recently widely quoted for implying (or, more accurately, saying) that books with reader-friendly characters are “slightly infantile”, while Sarah Slean during this year’s Canada Reads debates insisted that she didn’t think literature was for enjoyment. As I am learning (see: right sidebar) Robertson Davies felt trapped by this prejudice as well. His daughters remember him reading Huxley and noting “ah, so you can be light and literary” and yet years later when he failed to win major recognition for his body of work (it was once or twice whispered that he was in contention for the Nobel) he believed it was because his books were “moderately comprehensible”.

Lubbock believed books were for “wonder and wondering” rather than for information or privilege. I doubt very much he meant they were exclusively for wonder and dream – just that part of the value of literature is the way it can spark the reader’s imagination and inspire her.

“Inspiration” is one of those words that has got a bit of a raw deal lately, having been (to borrow Heller’s term) “Oprahfied” to mean 7 Ways to Get to Yes (with Chicken Soup) rather than the breath of originality that separates a work of routine from a work of greatness. Do we let books inspire us anymore? And when was the last time you read a book that you could call inspired? While there has been excellent writing on the offer in recent years’ fiction, I can’t honestly say I’ve seen or heard of much really inspired writing. It seems to me that it is easier for a writer to antagonize the reader than it is to inspire her. I’ve read a lot of “great” books from lauded authors in the last five years which read like a litany of the worst things that can happen to a person, invariably written by people who’ve never suffered much at all but who imagine that hardship must be something like Fear of Death or Godlessness or some other engrossing concern of the awakening adolescent. Not enough tragedy for you? Well, throw a drug addiction in there. And take ten years off the life of the protagonist. Make her sixteen. No, fourteen. Ah hell, twelve. And we need at least one rape and maybe some incest. Now we’re getting somewhere, this is the soul of humanity! (*tongue in cheek*)

It’s a hell of a lot harder to delight and transport the seasoned reader. To write that book that lodges itself in the heart of the reader and becomes the catalyst that changes her life. A lot of books claim to “change the reader’s life”, but how many really do? I can say I’ve had my life changed by a special couple. And I’d love to come across another someday.

George Steiner said, not very long ago, “I don’t find literature very exciting at the moment…Not all periods have major literary genius.” A sad sentiment. Perhaps we need a little more of Sir John Lubbock’s imagination and enthusiasm today; a new 100 Books picked, this time, for pleasure. An inspiring list for today’s writers and intellectuals to remind us that wonder, optimism and enjoyment aren’t naughty words and aren’t just the indulgences of idle people.

April 1, 2009

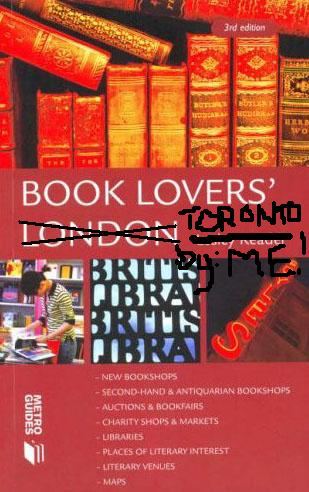

Book Lovers’ Toronto: Introducing the “Events” Tab

A couple of years ago I found myself in London (England) for exactly one day. It was a tough choice, but I opted to spend the day engaged in bibliotourism. This was made a great deal easier by a book I’d picked up in town: Book Lovers’ London by Leslie Reader.

This book is a gem. With no trouble at all I’d mapped out a route through as many used and rare book stores as I could get to, and was able to see an unbelievable exhibit of Holy Books put on by the British Library (including Gutenburg Bibles, scraps of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Qur’an of Emperor Babar and much more). I assumed the book was part of a series, and planned to get copies of Book Lovers’ guides to other cities.

I’ve since come to the disappointing realization that Book Lovers’ London is the only book lovers’ guide out there. But every empty gap is a great opportunity, right? I’d like to make a case for a Book Lovers’ Toronto.

You’d never know it, but Toronto is a fantastic city for the bibliophile. From its world-class events like the International Festival of Authors and Luminato and the literally hundreds of signings and readings around town to world-famous booksellers, collections and book sales, Toronto has enough book sites, events and exhibits to keep a bibliotourist entertained for a week.

Toronto is home to the fourth-largest University library system in North America (after Harvard, Yale & Illinois), including the largest repository of publicly accessible rare books and manuscripts in Canada. We house Canada’s major collection of speculative fiction and popular culture as well as Canada’s oldest science fiction bookstore. We have neighbourhoods where so many internationally-acclaimed writers live that the area is affectionately referred to as the “Writer’s Block“. We have statues of our poets and small presses open to the public. We have had two books written on that subject – Toronto – A Literary Guide by Greg Gatenby and Writer’s Map of Toronto by John Colombo (not entirely up to date either of them – nevertheless.) And on and on.

The “new book” events – the Festivals, the signings and the readings – are fairly well covered in the media. Publishers and promoters put a lot of money, time and effort into getting the word out there. As much as we’d like to think the aim of these events is literacy and cultural edification, they’re also really about selling books and that’s a cause that seems to justify publicity.

But on the used-and-rare end of the book spectrum we have a less cohesive “scene”. No one giant body stands to make money from these exhibits and events and no PR people are employed. Rare book people – sorry kids – are also an eccentric and slightly antisocial lot and tend not to strive for inclusion. The product – old things – also doesn’t lend itself to a media-savvy, internet prevalent crowd. This hurdle didn’t stop Leslie Reader, though, and it won’t stop me. So I introduce to you the Events Tab.

I have tried to collect a comprehensive list of books events and exhibits which might otherwise fall between the cracks, events not loudly trumpeted by their sponsors. Most of the listings are exhibits but I’ve also tried to compile a list of book fairs and sales in the area. Whether you are a native Torontonian who didn’t realize these events were available for your enjoyment or a visitor looking to absorb another dimension of the city’s rich literary offerings, I hope you will find these listings useful. And I’d love to add more! Always feel free to email me at charlotte@once-and-future.com if you think I should list something I might have missed.

March 30, 2009

Diversions, Distractions and Diabolical Deeds: Entertainments for a Darkened Room

What a weekend! The weather Saturday was amazing and facilitated long-distance trips to some Toronto booksellers I don’t usually have the pleasure of visiting. They were very nice about letting me photograph some books and even nicer about letting me buy some, and a very good time was had by all involved. My eight-month-old was awarded the “best behaved baby” award in two bookstores before having a total meltdown at the Lillian H. Smith branch of the Toronto Public Library, requiring my husband to have me paged from where I was hiding on the fourth floor- oops. Still, the project was entirely successful!

I present to you the Inklings Community Book Collection for March – Diversions, Distractions and Diabolical Deeds: Entertainments for a Darkened Room, in honour of Earth Hour.

March 27, 2009

Contest: We Bring the Ages Online

Welcome to Friday! This week Inklings presents to you an activity which I hope to repeat. Part scavenger hunt, part bibliophile convention, and part Web experiment; it’s The 1st Periodical Online Book Collection!

Um, what? Well here’s the deal. Periodically, on a Friday, I am going to propose that we build a virtual book collection. I will announce the theme of the collection and offer up a couple examples of books that might be included, and then leave the rest to you.

How will this collection be built? In images, descriptions and good faith. Find a book that you think would fit in our collection. Then take a picture of it and email me that picture along with a note on where the book was found, and why you think it belongs in the collection. Any bibliographical information would also be nice. On Monday I will post all the entries in one “catalogue” of our collection and tah dah, we’ll have an instant digital exhibit of a book collection!

That’s it??? Well, I have one rule. You do not need to own the book you submit, but you must encounter it IN REAL LIFE. No images gathered off the web! The book can be used or new, common place or rare. Go to local bookstores, libraries, universities, museums, friend’s houses – I don’t care, but you must be able to take a picture of the book you submit in the REAL WORLD. And be creative! I like quirky and unexpected interpretations of a topic. Feel free to be ironic, meta, traditional or fundamental. I will propose themes which are, I hope, broad enough for multiple interpretations.

But why? Here’s two reasons off the top of my head: 1) I am a big supporter of books-as-objects and local book “scenes” and would like to celebrate both by encouraging a collective tour every so often. Who knows what we might discover by getting out of our houses and into the book world? and 2) I will be offering A PRIZE to the “best” entry! I don’t know what yet, but it will be booky. The person who submits the entry that I deem to be the gem of the collection will win.

***

Now, because this is my inaugural collection and I don’t know yet how many people are interested in my game, I will be contributing heavily to this first collection. But please, join me in my search and lets see what we can build this weekend.

Alright, with only a little more ado, I present to you this Friday’s topic and theme. In honour of Earth Hour this Saturday at 8:30pm, I propose we collect a virtual library on:

Diversions, Distractions and Diabolical Deeds: Entertainments for a Darkened Room

And to kick us off I give you two examples:

What? The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1001 Nights Deluxe Edition tr. Malcolm C. Lyons, Penguin Classics, 2008

Found: In my dining room.

Why? I give you the original crepuscular pastime, good for about three and a half years:

Or here’s another idea:

What? How to Commit a Murder by Danny Ahearn, Washburn, New York, 1930.

Found: In my bedroom. (Hm….)

Why? Ahearn says “Naturally, to convict a man it takes four eyes and not two” and while he includes useful advice on how to knock off witnesses, you could also just commit your murder IN THE DARK.

Got the idea? great! Of course feel free to ask any further questions. Entries should be emailed to charlotte@once-and-future.com by 6am Monday, March 30th. Good hunting!

March 25, 2009

Parable of the Decrepit Book

Monday I had the privilege of attending a lecture at the Royal Ontario Museum called “Canadiana Treasures from the Rare Book Collections of the ROM”, given by the head of the library and archives, Arthur Smith. Not surprisingly, the ROM has some really priceless holdings, including the 1613 Les Voyages of Champlain, Des Barres’ Atlantic Neptune, 1st editions of Susanna Moodie’s Roughing It In the Bush and more. In many cases they have books in conditions unmatched anywhere in the world (not always hard to do, considering many of these books number less than twenty in the world).

One work, though, really stuck in my mind because of the story associated with it, and that was the ROM’s copy of the 1866 Buch das Gut, enthaltened den Katechismus, Betrachtung or, as it was introduced to us, the Mi’kmaq prayer book. This is a fat little book of prayers written in Mi’kmaq hieroglyphics, this edition printed in Vienna. Unlike the other books we saw, the prayer book was not at all in good condition. The leather covers were falling apart, the book had been written on and the pages appeared largely unbound. Indeed, Smith noted that the book had been found “languishing in a Toronto auction house” because it was deemed to be in too poor a condition to be of any value.

A page from the Mi'kmaq prayer book - but not the ROM's copy.

But the ROM bought it anyway. As the story goes, the shipment of these prayer books from Europe was largely lost at sea, and so very few copies remain. A dilapidated copy is still a copy, valuable even in this condition. The librarian went about contacting the owners of the other known copies (exclusively, as far as he knows, institutionalized) to compare his, and found that the ROM’s copy was the only one in the “damaged” condition. Pity, right?

As it happens, not such a pity after all. The origin and use of Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs, as it turns out, is a source of some contention. This story goes that a 17th century Catholic missionary witnessed the Mi’kmaq using porcupine quills to press shapes into bark, then adapted and expanded this system of shapes into a written language that could accommodate Catholic prayers. This story is thought by some to be apocryphal, and they argue that the “language” was invented entirely by the Catholic church, and no actual Mi’kmaq read it.

Except that some, very evidently, did. The evidence is all over the ROM’s prayer book. The geneology of the owning family is carefully inscribed on the first page, and the book shows evidence of repeated readings throughout. The value of this book is in it’s poor condition, in the use and character of this individual copy.

Not every book can be hoarded and not every copy should be archived, digitized, conserved. But sometimes it’s worth remembering that there’s more to the value of a book than the printed contents in their idealized form (sorry, bibliographers). There’s as much story to be gleaned from the marks, wear and scars. From the ghost, as they say, of the “hand that touched the hand”.

The ROM library and archives are, incidentally, open to the public for research. You can’t withdraw books as in other libraries, but you can use the University of Toronto library system to search the museum’s holdings and can request and inspect the books in the museum’s reading room.

March 23, 2009

The Incredible Instant Book Collection!

Last week, Abebooks.com’s newsletter, The Avid Collector, arrived in my mailbox with a headline that went something like this:

“Own A Full Collection of All Hugo And Nebula Award Winners For $110,000”

The headline seemed almost absurd to me. Who has that kind of money, especially nowadays? Aren’t the ultra-rich getting out of these sorts of frivolous things? And if some rich person were willing to suddenly want an instant book collection, why would they want a genre collection, rather than something more prestigious, like Booker winners, or Nobel winners? Who on earth is this being marketed at?

I’d almost dismissed it as a curiosity when I happened to notice that one of my favourite local booksellers, Contact Editions, is also, as of this month, getting into the sale of complete collections. Something is going on here. This is some kind of new thing.

Or rather, this seems to be a resurgence of an old thing. Rich and influential people have long looked to own personal libraries as a mark of wealth and social stature. Any specific interest in books was less of a factor in the accumulation of these collections than the prestige of owning them, and so secretaries and dealers were often employed to put together “instant” collections for people who were more concerned with the look and value of the books in their library than their contents.

But we’re a long way from the Gilded Age, and a good library doesn’t impress these days quite the way, say, a 120 foot catamaran will. Beyonce and Jay-Z drink champagne on the deck of their boat, not the fat armchairs of their libraries. And we’re hardly in an economic climate that suggests hoards of new millionaires looking to buy into the hobbies of the rich and powerful. So?

I think the answer is in the motives of the bookseller rather than in the emergence of a new market, and this alarms me. We’ve all heard that we’re in the middle of a mass bookstore culling, with independent booksellers dying off in waves first to the emergence of bookselling superstores like Borders & Chapters/Indigo, and then to online sellers like Amazon, but nowhere is this more true than with used and rare booksellers. Theirs is a more specialized product, and in a book world growing more and more towards reading as a temporal activity rather than books as an expression of permanence, they’ve been closing shop in droves. Not that used and rare booksellers are vanishing – they are simply closing their doors and moving online, to catalogue sales and “by appointment only” availability. They’re focusing once again on their specialized audience, the privileged buyer.

The privileged buyer collects books in a particular way. To a large degree, they want the end product, the collection, more than they want to engage in collecting. The collection is an investment or a trophy, something to relish having but not necessarily getting. Many of these buyers represent institutions – universities or libraries – and use booksellers as a sort of outsourced scout or broker. They don’t need, necessarily, to see the book. They can form a list of what they’d like to own at home, then have someone else hunt them down. They pay the asked price and have a library to show for it. And so, yes, selling collections ready-made through catalogues or websites works, because it wasn’t as if these buyers were every going to go spelunking through the dusty old boxes in a bookseller’s overstock room anyway.

This is “book collecting” to the extent that paying a mortgage is “house collecting” and it makes me really sad. Yes, many of these wealthy book collectors are true book enthusiasts who take real pleasure in receiving that phone call from their dealer telling them they’ve located a rare book that the collector has long lusted after. But almost every one of those collectors started as a younger, less affluent person who honed their taste for books by encountering the real thing in public, open bookshops. Nobody learns to love books on the internet. And there will be no market for “full collections” if bibliophiles aren’t able to first whet their appetites by discovering individual volumes.

We’re not likely to revert to being a society with a rich, Oxbridge-educated elite who monopolize and sustain the rare book trade and so any trend towards selling “collections” seems to me to signal one of two things: either booksellers are going to find themselves with fewer and fewer customers as their old customers die off, or else the rare book trade is going to become the private scouting arm of institutional libraries. Is this a desirable future? I don’t desire it, being a not-wealthy, young, non-institutional collector. Am I alone in that, I wonder?

This Friday I want to start an experiment in amateur book collecting, right here on this blog. If you’ve made it this far (I have overstepped my 96 seconds, I’m afraid) and are interested in book collecting, Web 2.0 experiments, or just scavenger hunts, I ask that you tune in then – and invite your friends! The more people who participate, the better. I’d like to demonstrate that we can build something great the (mostly) old-fashioned way…

March 18, 2009

Conversing with Digital Texts?

There’s a lot of fuss and bluster in book circles about digital book technology like the Kindle which I am not going to weigh in on in any serious way because I have not actually ever handled an ebook reader and I am not entirely sure what capabilities they do and do not have. That said, I was sorting my books yesterday (something which happens on a semi-regular basis, as it brings me great pleasure) and wondered how I would replace my written “tags” if I were to convert for whatever reason to an entirely digital library. The Kindle has a little keyboard on the bottom, I see; while my mother confesses to printing out pdfs of texts in order to annotate them. Neither of these solutions entirely appeals to me.

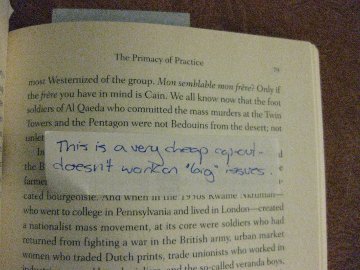

Most diligent readers keep track of their thoughts on a text as they read. The most common habit these days is to keep notes in the margins of a book, creating a gloss to the text that is referred to as “marginalia”. I find attitudes towards marginalia vary significantly between readers.My own opinion is that unless you are or are intending to become Samuel Coleridge that you should keep your notes in a book to a minimum, but my squeamishness towards defacing books doesn’t seem to be shared by the legions of bold, ballpoint-pen-bearing readers that populate, especially, academic libraries. Yes, the marginalia of great readers and writers can be fascinating, and a source of some really excellent criticisms on a text. But I can’t stand the unintelligible scribblings of former readers scaring my book’s pages, and I do future readers the favour of keeping my opinions out of their text as well. But that’s just me.

That isn’t to say that I don’t keep conversation with my books. I waver between two techniques, though one is more of a bad habit than the other. The first, the bad habit, is to note my commentary on little scraps of paper that I leave marking the pertinent page. Many of my books are marked with enough of these little scraps that they look like they’ve got little paper pigtails. This leaves my books clean, and certainly helps me find important pages quickly. But unfortunately my notes also tend to slip out of their books, leaving important passages forever lost. I spent too many hours out of last month trying to find a quote from Robertson Davies on the importance of reading Dumas to young boys that I *swore* I’d marked. This is, however, something which margin-scribblers must struggle with as well. Knowing you’ve seen something somewhere isn’t enough of a roadmap to finding a note in a library of books.

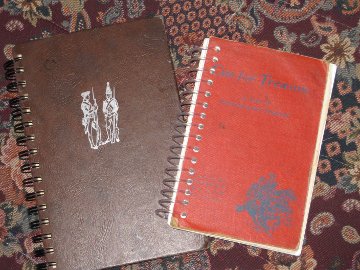

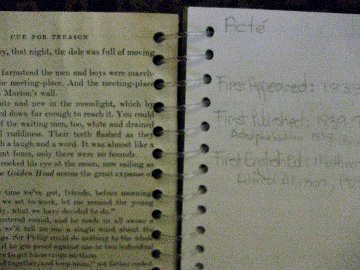

My other habit is to keep a notebook at the ready while I am reading, my loci communes. This is an old practice with pedigree and some wonderful perks. Not only can you look back to what you were thinking when you read a book, but you can organize your notes however you like – perhaps keeping a section for favourite quotes, another for future writing ideas, or collections of information pertaining to specific subjects. Writing an essay on Emerson? Maybe you’ve been keeping a notebook of thoughts and quotes pertaining to Emerson, that roadmap to your library. But open-ended organization of your thoughts isn’t the only benefit, nor is the fact that your books will stay fresh and clean. These notebooks become wonderful additions to your library.

Me, I am a sucker for snazzy little notebooks. I’ve been drawn to blank notebooks ever since I was a kid. They were pre-bound novels in potentia. A story handwritten in a notebook was automatically a published book, thought eight-year-old me. And weren’t spell books in all the stories just handwritten books of arcane recipes? These days I buy notebooks with almost as little restraint as I buy books because Toronto seems to be overflowing with talented paper artists. I’m especially partial to these little numbers: notebooks made from recycled old novels. Even a dedicated book hoarder like me has to admit that there comes a time in a book’s life when it has no future except in the recycling bin – but wait! I’ve seen these journals called “upcycled journals” – you can even get ones with old board games (Scrabble, anyone?) or VHS slips for covers. How cool is that?

Maybe the biggest perk of my loci communes is that, in any future ebook apocalypse, they remain useful and relevant. The electronic versions of marginalia and tagging still have their shortfalls over the real thing. Scanning a book for the visual cues notes and tags offer becomes difficult. Search functions rely on memory, rather than aid it. And does an electronic scroll have the margin space available for good notes? Perhaps they could (or do?) offer a function to watermark notes over the text – hell, they could allow you to save the annotation as a separate file to overlay any copy of your book. Torrents of professional annotation, anyone? Forgeries of celebrity marginalia? There’s leeway for some interesting speculation here.

But none of it makes me feel quite as secure as knowing that, in the event that I were trapped in a world with only an ebook reader and a good craft fair circuit, I could still furnish a library of worn cloth covers, good paper and sewn bindings, filled with the memories and impressions of a lifetime of reading. It certainly beats sheafs of unbounded printed pdfs!