March 16, 2011

Panicked Ranting in eBooks

Everything is not just going to be okay. I don’t care what publishers, the Globe and Mail and Margaret Atwood have to say. Increasingly I am finding that the scope of the ebook debate is being narrowed and dominated by certain interested parts of the book chain. Sure, many things about the ebook are wonderful. And they aren’t imminently going to destroy any part of publishing, Canadian literature or culture. But it’s a precarious perch the ebook sits on, and none of the interested parties seem aware of, or willing to discuss, this fact.

Over the last couple of years I have had and expressed grave concerns about elements of a theoretical digital future, and though I sit and wait patiently for these issues to surface, we seem to be coming further and further away from them. It’s because these are Big Picture issues that seem to exceed the scope of any one publisher’s five-year plan, or an author’s concern over becoming published. So listen, let me be crystal-clear about my fears. Do feel free to direct me to the appropriate pat answer.

EBOOKS ARE A TOP DOWN PRODUCT. Cory Doctorow or Joey Comeau’s latest schemes to retain control over their own art, distribution and sales included, ebooks are a highly specialized commodity which do not exist but for the grace of large corporate entities. I can not write an ebook without the help of HP, Adobe and Microsoft, and you can’t read one without Sony, Kobo, Apple or Amazon. Whoever wrote that file, however you read it, you are depending on technology which probably won’t work in five years, let alone fifty or two hundred. Big companies made the bed you lie in and their future is your future. Do they represent your interests? This is of archival concern of course, but it’s more than that.

I am concerned about the current format wars. A number of players – Apple and Amazon chief among them – are attempting to monopolize the ebook market. Proprietary formats and a “leasing” model to their business plans mean that their products are not transferable and adaptable to infinitely new reading devices. Eventually they will either “win” – gain a large enough permanent market share that it’s worth it to publishers to continue producing multi-format ebooks – or “lose” – fail to get that market share, and give up the project. Those defunct and discarded formats represent loss of information.

Amazon scares the bajesus out of me, not because they’re the biggest competition to any bookseller at the moment, but because their business model looks unsustainable to me. Books, unlike many consumer products, aren’t as easy to force into a discount economy. For starters, it really matters to a reader whether their book was written in Canada or in China. So while maybe you can look the other way and buy cheap, slave-made rubber boots from Walmart because, you know, they were only $5.99; you aren’t going to read a book by some faceless cheap labourer just because it’s cheap. At the end of the day, you want the new Philip Roth book and that comes with certain costs. Roth is a big one – the man would like to get paid. Producing his book comes with more costs: editing, formatting, design, marketing, publicity. These aren’t assembly-line skills and believe me, if they could be easily outsourced to Indonesia, they would be. As it is publishers have cut back on all kinds of former publishing necessities like editing and fact-checking because they need to keep prices down.

So Amazon’s predatory insistence that the price of books has to come down has a floor. They will never go lower than a certain point. Where that point is is a huge battle ground right now, and it really doesn’t benefit Amazon at all. People who try to comply go out of business, and people who stand firm either go out of business or keep prices up. The author, who is ultimately the product you are looking to buy, just goes to the standing publisher who can give her the best deal.

I have news for you, bargain-hunter: when Amazon sells you a new book for 50% the cost of the same book from an independent, it’s because someone is losing money. They’re either trying to create a loss-leader, a hook, or they’re trying to artificially force other publishers to “compete” with that price. Nowadays, they’re trying to sell ebooks at a loss so they we can all jump on board the Kindle and they can either make money on the technology alone or they can win the format war. It’s a big friggin’ gamble. If they lose, they fold up. And guess where your ebooks go? You never owned them, friend. And if it doesn’t seem likely this is going to happen in the next five or ten years, wonder where Amazon will be in fifty years, after your lifetime of book buying.

Yes, that might not matter to the buyer. It has been pointed out that the types of ebooks sold tend to be transitory desires. The kind of book you might leave in a hotel room. If you lose the “library” to a technology upgrade or a corporate bankruptcy, maybe you don’t care. But I’m skeptical of this idea of the two-tiered book market. Why on earth would any corporate publisher continue to sell paper books when all their money comes from selling frontlist blockbusters in ebook format? Ideology? And to whom would they sell these paper books anyway? Bookstores are the real vulnerable partners in the book chain. We don’t make or sell ereaders and, as of today, in Canada, we can not sell ebooks. We can only sell paper books. If even as many as 20% of my customers switch to ebooks, I go out of business. Without meat-space bookstores selling dead-tree books, the market for real books gets more and more marginalized. So you might not care about your digital book collection, but will publishers continue to support the paper book “backups”? An even smaller market means the cost of the book goes up – again – which leads to even fewer buyers. Amazon may or may not consider it worth their while to deal in “premium” Real Books. Buyers may prefer digital books to the inevitable POD (print on demand) ones, which remain hideous.

Obviously we’re not there yet. Many, many people still prefer real books. But it drives me nuts when I listen to discussions between publishers and writers, for whom, frankly, the question of digital-or-not-digital is moot, since their product is the content, not the format. They seem to forget the roles of other parts of the book chain. Typical, for people whose vested interest in the product vanishes the minute it is sold. Where are texts without bookstores? Without a second-hand market? Without reliable archives? Under censorship? To people who can’t afford to upgrade hardware every 5 years? Does it matter to them? Not a whit. As long as the frontlist sells, somehow, to someone, through anyone.

Now I want to stipulate that I don’t feel my apocalyptic vision of the digital future is in any way inevitable. But I think it will be if we keep treating Amazon and the big book chains as the benevolent godhead of book distribution. Publishers do this, writers do this, and increasingly, customers do this. Doctorow and Comeau aren’t just desperate writers who can’t get publishers, they’re authors who glimpse the danger of a book future where the control of big companies isn’t questioned. They are also, unfortunately, dependent on Our Corporate Overlords to produce their product, but at least the first glimmerings of awareness are there. The digital future is going to be bleak unless we question the health of a market run by a few players.

We all know the possible solutions. We need to settle into an open-source ebook format which can be freely exchanged between platforms. We need to open the market up so that independent players can sell the same ebooks that the big chains can. We need to stop pushing for ever-lower prices on texts. Publishing and readership will remain healthy if and only if we consciously address the format’s weaknesses. Tell me exactly what is being done to make sure these texts last. To guard them against censorship. To allow small and large publishers equal access to readers. To manufacture, distribute, and dispose of the delicate and expensive ereader technology equitably. To protect all of our joint investments if, god forbid, some discounter’s insane scheme to control the industry doesn’t quite pan out.

Stay tuned for next week’s installment: What Purpose Do Booksellers Serve, Anyway. Maybe by then I’ll have rooted out some answers for you.

March 10, 2011

Yay!

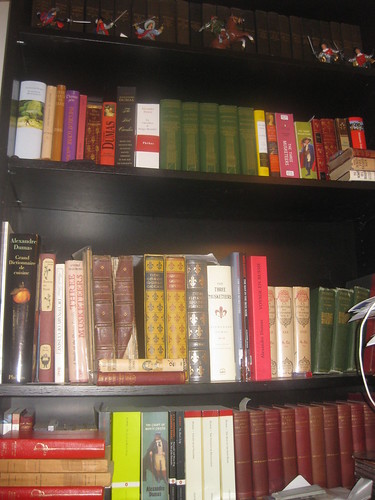

I came home last night to find a giant box-in-a-bag on my front porch. It was the first of three shipments from the Folio Society!

Inside was not only my four Fairy Books and a dictionary/thesaurus set, but quite a lot of bubble wrap, which was greatly appreciated by the young miss.

Now they live on the newly-named “Folio Shelf”, where they are getting cozy with some of my older Folio Society acquisitions. Except for the first, the Blue Fairy Book, which is our new bedtime reading.

March 3, 2011

Returns Season

It’s returns season at the bookstore. It comes for all bookstores: it means our year-end is coming and we need to get as much unsold stock out of the store as is reasonable. I know some big book chains who shall not be mentioned have had, in the past, a reputation for abusing returns privileges with distributors, but for us the right to return is a necessity of survival.

We stick to the rules – we never return more than 10% of our orders to the publishers – and I like to think it benefits everyone. We gain the flexibility to gamble on unknown publishers or authors without fear of getting “stuck” with the book. We can order quantities of books for university and high school courses that might otherwise be foolish (after all, when a prof tells you “I have a cap of 200 students” this sometimes means “… but only 44 signed up”, and nobody would ever tell us. Not to mention the sometimes enormous numbers of students who choose to buy their books elsewhere, use the library, or flat out not read the book. Anyone who thinks university business means guaranteed money is kidding themselves.)

We also have a private policy of not sending books back to certain distributors unless we really have to. We will keep lots of things well past the return deadline because we really ought to have it on the shelf (nevermind that something like Roland Barthes’ Mythologies might only sell once every three years – we should still have it.) We keep small Canadian independent publishers almost indefinitely because we feel bad sending the books back to them. But on the whole, we need to be able to send back a lot of the stock every year to balance the books, clear out some space and cut old losses.

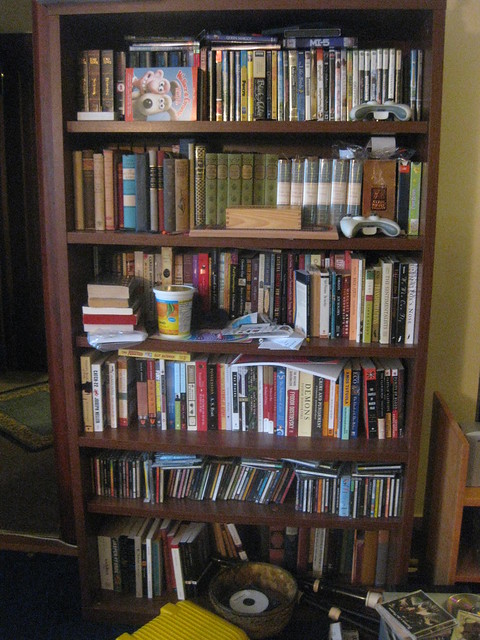

This is a dangerous time of year for yours truly. I can’t send a book back that I’ve had my eye on all year. I have to “intercept” a lot of titles now as I feel it’s my last chance to get them before they go back. And then there’s the sale books – oh yes. Anything that’s past the returns deadline and considered no longer good for stock we cut to 50% or 75% off. You better believe I get first crack at those!

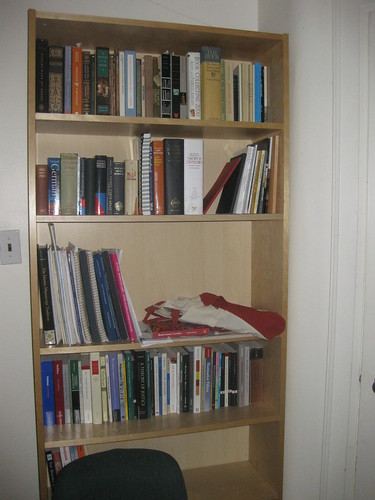

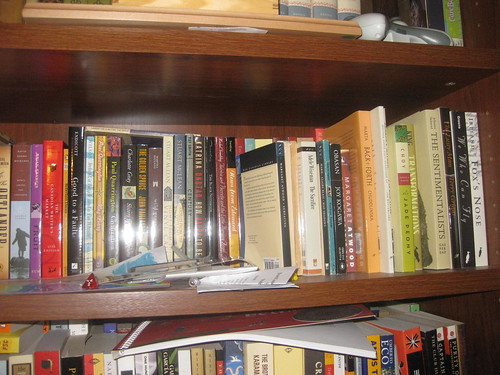

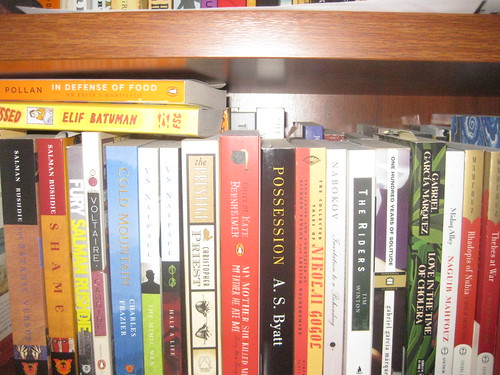

As of this morning, the damage looks like this:

And this is why I’ll never own a house…

March 1, 2011

This is the Kind of Thing That Keeps Me Up At Night

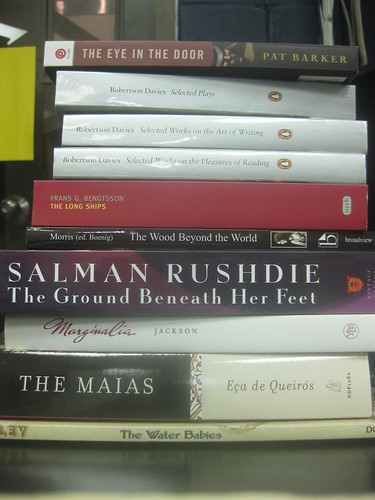

This weekend I started on the epic task that is cataloguing my “extra” books, probably for sale. I’ve dabbled with the idea of setting up a little shop at abebooks.com for a few years now, but nothing jogs backburner projects quite like upcoming maternity leave.

Among the books I need to cull from the collection are the “extras” in my Dumas collection. This should be easy. I’m up to fourteen copies of The Three Musketeers alone (if you count the purse); you’d think there’d be an easy choice or two in there. Heck, I have several exact duplicate editions in the collection.

Except that’s not quite true – exact duplicate is a hard thing to find. I maintain the practice of “upgrading” copies – buying duplicates of books I already have if the newer copy is “better” in some way. Of course, “better” is a completely elusive concept, especially when dealing with books which have been released in thousands of editions over hundreds of years. Nevertheless once in a while I do pick up second copies of theoretically identical books, only to find they aren’t identical enough to make an easy decision.

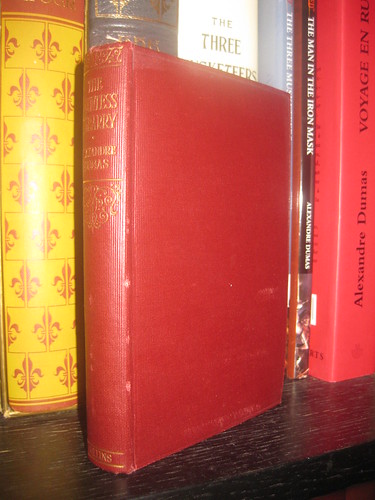

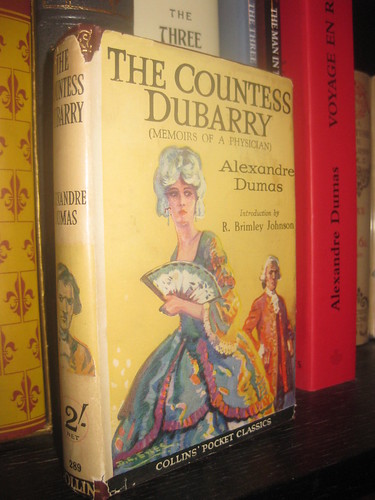

Here’s today’s conundrum:

On the left, my old copy of The Countess Du Barry by Alexandre Dumas, published by Collins Clear-Type Press around the turn of the 20th century. On the right, the new copy of The Countess Du Barry by Alexandre Dumas, also published by Collins at the turn of the 20th century – but with dust jacket. This ought to have been a no-brainer update. The dust jacket has even kept the covers of the right-most book in cleaner condition. The maroon is darker, the gilt is stronger. But a few moments after settling into my new copy I noticed two problems: one, the ink on both the type and the plates in my new copy was extremely light: faded or never printed properly. And two, the pagination was different.

I whipped up a quick collation formula for both books to suss out the difference. The differences were slight but there. The plates were inserted in different places in the 2nd copy, though as plates aren’t usually included in the page count, this didn’t account for the difference in pagination. On the other hand, the first copy has a half-signature (sometimes called a quire) worth of advertising at the back. The text of the book is the same – identical in fact, I’ll get to that in a second – but because the book had been laid out with this extra apparatus in mind, the pages were printed in different signatures, and folded into the book differently.

With me so far? Okay, so who cares, right? Well, based on the evidence, I can draw some conclusions. Collins Clear-Type Press might have been based in “London & Glasgow” (as reads the title page) but, in fact, Collins Pocket Classics were printed all over the place, notably in the United States. Stereotypes of the pages (full-page casts) would be taken and shipped to big markets to be printed locally. Now, stereotypes could be used again and again, and it’s quite common to see real degradation in the print quality of these prints. The advertising in my first copy indicates the market was British, so it is likely a London print job. I suspect my “new” copy was printed in the US later, from stereotypes. The advertising would have been removed as it wasn’t relevant to the local market.

So I have one older, reasonably well-printed copy of a book with complete with advertising pages, but no dust jacket. Then I have a second, poorly-printed copy, printed later probably in another country, with no advertising but with a dust jacket. What’s a girl to do? My first instinct (bad book historian!) was to take the dust jacket from the second book and put it on the first, getting rid of the now-jacketless American copy. But this is fraught with dangers if authenticity is one’s goal. Who knows what the dust jacket of the British edition looked like, or if it even had one? Who knows if the dust jacket on the American one is even authentic – maybe someone switched them earlier? There’s a price on the spine that looks like British notation to me. Until I know, I’m inclined to keep everything as it is. Sit tight, wait for more evidence.

And in the meantime, I have five copies of the Countess Du Barry on my shelf, two of which are nearly identical. My culling project is off to an inauspicious start. It’s a hard thing to part with books! But I’m forging on. Space must be made.

February 25, 2011

Wild Books I Have Known

Steph at Bella’s Bookshelves recently published a lovely post about “37 books that I’ve known and loved enough to feel a sense of familiarity and affection when I see them on my shelves.” It got me to thinking about my own personal reading attachments, especially in light of the fact that for the last few weeks all I’ve been able to bring myself to read is Frank Herbert’s Dune chronicles, for probably the 10th time. A devoted reader is lucky when on that rare occasion a book grips her enough to really get lost in it, forming an attachment for life that’s hard to describe in terms of any other media, except perhaps film.

In my own experience, I have only really fallen in love with one or two books every couple of years. Even that, though, amounts to quite a number of books – so I thought I’d offer an even more specific list. I was thinking about what books formed me. Not “which books were my favorites” or “which books are the best”, but which books really and completely seized me and changed the way I thought, or changed the direction of my life. I look at them, and have to wonder: those people who don’t read – and there are a lot of them – what forms them? Because god knows who I would be without books. Nothing like me. And god knows who I would be without these specific works.

What about you? What are the books that built you?

The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis

My mother read this book to me for the first time when I was six, and it terrified me. I don’t remember being terrified – I remember being a little bit alarmed by Fenris Ulf – but apparently I was alarmed enough that my mum stopped reading at this point and didn’t come back to it for the rest of the year.

But she did eventually read them all to me, and then I read them again myself, and again, and again, and again. I was so convinced that Narnia was a real place and that with enough determination I could get there that I absolutely obsessed night and day over it. I read the books in painstaking detail looking for clues about how to get there, or evidence that The Last Battle was in fact a forged work by the White Witch designed to fool us into thinking Narnia wasn’t there anymore so that we (read: clever and adventurous children like myself) would stop showing up. I had every bit of Narnia paraphernalia you could name, lions were my favorite animal, and I even tried to read Lewis’s sci-fi in the hopes that they contained more clues to the true fate and location of Narnia. They, for the record, did not.

I don’t remember giving up on Narnia until I was into grade six – and even then it was only because I moved to Calgary and my co-Narniite (Livia, my then-best friend) moved to London. I would have been 10 by then – so Narnia seized me for about four solid years.

Dune by Frank Herbert

I read Dune the summer between grade eight and nine – all the rest of the series too. This was a mind-blowing experience. Call it egoism, but I seemed to have decided that becoming an omniscient, timeless, infinitely-wise super-being was something immediately within my grasp. Not only that, I was sure that the route to Wisdom was in A) all the adult reading I could cram into my head B) transient, mind-altering ingestibles (i.e. the Spice, or chocolate covered coffee beans) and C) totally obsessive introspection and/or navel gazing. I also spent a good deal of that summer teaching myself tricks of self-control, like moving only one muscle with the exclusion of all others or inducing sleep at any time or place (in myself, of course. I was big on breathing excersizes.)

I also fell in love with Duncan Idaho and another boy on my soccer team whose name was (coincidence? I don’t think so.) also Duncan.

Mostly, I read anything which I could pretend had “value” (i.e. no more pulp!) and thought about it until my head hurt.

Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

It was Kurt Vonnegut that made me want to become a writer. Not that I had any intention of writing what he did – although I kept a journal trying to record amusing, cynical and anecdotal observations about the real world – but he gave me a different idea of what writing could be. It wasn’t just disembodied narrative, a story told by anyone to anyone. You could be a character, the teller, and pour yourself into the reader with great effect. He also taught me irony, deadpan and sarcasm – oh how I absorbed them. Thank god by the time I read Vonnegut I was beyond obsessing over the contents of a book – although I did recognize myself as a Bokononist for some time. He was the first I read where it was the form of the book, the writing – not the story – that impressed me.

Dreams Underfoot by Charles de Lint

This is one of Charles de Lint’s many books – and for whatever reason, the one that stabbed me in the heart. This book precipitated me leaving home. The year before I went through a very short Once and Future King phase – a book which I debated adding to this list but left off because I can’t quantify what it meant to me as well – in which I was going to be a filmmaker and my magnum opus was going to be a three-part O&F film. I still have a script I did up of the first half of The Sword and the Stone. For whatever reason I had become disillusioned with my film-making skills and was desperate for something more to my talents. In Dreams Underfoot I thought I found it.

I was going to be a gypsy, a transient, a busker and an artist as well as a part-time waitress. I couldn’t pick a favorite character in Newford (Jilly) so I wanted to be all of them. I really just suddenly identified very strongly with a lifestyle, a subculture, a people. I picked up violin again and taught myself to fiddle and worked out a comprehensive plan for hitting the road in a permanent sense. It changed my fashion sense, my outlook and my expectations. Finding these people made my heart soar. The only real letdown was when I finally got to Toronto and didn’t find a single like mind.

Good News for a Change by David Suzuki & Holly Dressel

This was a David Suzuki book I bought on a whim because I was newly into “collecting” books and, at Nicholas Basbane’s suggestion, felt my “collection” needed a theme. I was watching a lot of The Nature of Things at the time and for whatever reason decided I wanted a science/nature/environment themed collection. This was in hardcover, and the last copy available at Book City, so I bought it.

At the time I had re-enrolled at the University of Toronto (after a previous stint studying Celtic Studies under the aforementioned influence of DeLint) and was planning on doing a degree in French Literature to pursue my love of Dumas (you’ll notice his works are not on this list – I thought about adding them, but while I adore them, they haven’t influenced me much. They are simply the most indulgent works of literature to my tastes.) I planned to pursue a career in translation.

This book changed everything. I had always been politically-minded and prone to “debate”. My mother had been leaning on me to become a politician or a lawyer since I was ten. It had simply never occurred to me to take her seriously because I saw myself as an “artist” or at least “artistic” and felt I belonged more in the humanities. Literature, film, music. That kind of thing. But Good News framed everything for me in a whole new context: there was a battle going on out there to save every aspect of culture, science, environment and society and there were good people who just needed more bodies. There were very practical and reasonable things that needed doing and nobody seemed willing to step up and do them.

More than that, I had that epiphany. I was not particularly artistic. I have a talent for music, but this is really more to do with math and pattern recognition. It has more to do with logic than art. Every degree or project I had taken up designed to refine my life as an artist had flopped miserably. But what I was really good at was arguing. Fighting for things. Seizing the moral high ground and strong-arming the world so that it went my way. Well as it happens, these are very useful skills for activists. Why my career in the Environmental Sciences never went far is another story, but Good News catapulted me into four long years of an Environment & Geography degree.

Natural Capitalism by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins & Hunter Lovins

Paul Hawken and the Lovinses – this belong with Good News but they’re different entities. If Good News woke me up, this one gave me a specific direction. Unlike most activists, I am not a bleeding-heart lefty. I definitely believe in socialism, but for economic reasons. I am an environmentalist, but because I have a bee in my bonnet about efficiency, not because I think trees have rights. This is what kept me away from politics or activism for so long – I hated the way these issues had been marginalized, supported by the “fringe” and made irrelevant to people actually just trying to live their lives. Natural Capitalism became the book I most loaned to other people, and formed by philosophy of economics, environment and living for quite some time.

A Gentle Madness by Nicolas Basbanes

Having spent much of my twenties in the thrall of the politics of the environment, you might wonder how I got here today, a staunch and committed bookseller, collector, and blogger. Thank Basbanes. He was responsible for turning me onto my environmental degree as well, but once I’d come out the other side of that degree I found myself still more committed to my books than to some causes. I’d always read books and always collected books, but it wasn’t until the reading and collecting reached a certain critical mass that I realized I was never getting out of it, and I wouldn’t be happy if I ever did.

Later books of his like Every Book Its Reader and A Splendor of Letters kept nudging me more and more into the book hole. I became as interested in the reader as in the book. I became interested in collectors, collections, publication histories and bibliographies. I realized this was a whole life, not a hobby, and, once again, returned to school to study Book History. Unlike the frustration and disillusionment I’d encountered during my environment degree, I found myself encouraged and rewarded continually in Book History. And, after all, wasn’t this what I’d really loved all along – books? Many books caught my attention and enthralled me during my life, but Basbanes has the honour of being the writer that made me think about the meta-book, the world of being bookish. And the longer I live here, the more it is my home.

February 22, 2011

My Tax-Time Present To Myself…

I have always, always wanted to join the Folio Society. I remember being maybe 14, 15 and hoarding one of their little fliers (which came, I think, in a larger batch of junk mail) in the back of my diary for months, years, planning and underlining and circling my future purchases. Then there was some talk a while ago about splitting a membership with a friend or two, both of us buying a few books to make up our obligation without breaking the bank. But it never happened.

In more recent years I have visited their website a couple of times a year, always telling myself “I’ll join when they publish that thing; that shady, unknown future thing that I absolutely have to have. I’ll know it when I see it. That’s what I’ll join.”

That day has finally come. I signed up this weekend, and this is why:

The 1st Edition of the Violet Fairy Book

The other thing I’ve always, always wanted is a full set of all of Andrew Lang’s coloured Fairy Books. I lived and breathed these books when I was a child (it’s amazing the violence and misogyny didn’t scramble my brains, but this is a testament to a child’s ability to get exactly what they want out of a story and discard the rest) and thought as a young adult they would be the simplest things to collect; not so. The original Coloured Fairy Books are extremely expensive to come by despite being fairly common (as far as collectible Victorian books go) – the first volume, the Blue Fairy Book, might run as high as $10,000 and subsequent books are still going to cost in the $2000-$4000 range.

Dover's current paperback design.

Subsequent editions aren’t very pretty. Hardcover “library editions” were reprinted all through the 20th century but without the lovely gilt covers or, really, anything else to recommend them. Currently, you can buy the whole series from Dover Publications for like $15 a pop – which I did – but they’re exactly as ugly as you would expect a Dover edition to be (sorry, Dover).

The new Folio Society editions, on the other hand, are beautiful. As with all Folio editions, these are well made, beautifully printed books bound in hardcover with decorative bindings and a slipcase apiece. For this series Folio has also commissioned a different contemporary artist to illustrate each volume. If I had any hesitation it was obliterated when I saw that the first volume, the Blue Fairy Book, was illustrated by Vancouver artist (and bookmaker) Charles van Sandwyk. The five artists so far lined up to illustrate the Red, Yellow, Green, Violet & Brown books are no slouches either. I’m mad with anticipation to see who they get when (hopefully not if) they do the rest of the series.

My husband was slightly more skeptical then me – “So this is like Columbia House for books” he guessed. I got my back up a bit over that. Yes, it’s a book club that requires certain obligations of the member (in this case, buying 4 full-priced books over a period of time). But they aren’t out to scam you, and the product is very high quality. Further, though copies turn up in used and rare book stores fairly frequently, joining is the only way to really guarantee you’ll get these exclusive editions. (And I should note some Folio Society books turn up more frequently in bookstores than others – it is certainly the case that there are some books which are more rare than others.) They also publish books that are unavailable in any other edition – a quick glance notes Count Belisarius by Robert Graves, The Complete Tales of the Unexpected by Roald Dahl and Robert Lewis Stevenson’s The Isle of Voices and Other Stories.

And don’t get me started on the limited editions! Right now I’m just pleased as punch that I’m a member and can, for one year at least, buy lovely books at my leisure. Next on my schedule is their illustrated Possession by A.S. Byatt to replace my hideous movie tie-in copy. I can happily spend the rest of my year browsing the website and making wish-lists. Happy tax-time to me!

January 20, 2011

What kind of Bookie are you?

I waver back and forth every six months or so between my two great loves: books and books.

On the one hand we have books, the kind I sell and read, the kind I review, the kind we can all engage in because of their uniformity, ubiquity, and accessibility. These books are current and relevant to most people; they are supported by communities who are in turn supported by a vast network of publishers, creators, reporters and fans. Life with these books is exciting and relevant as well as personally fulfilling. There’s industry gossip, bookselling drama, public spats over criticism and clubs and challenges to engage in. These books are professionally relevant to me: I need to know them inside and out as a bookseller, and any future profession I might be made to take up will also likely hinge on my involvement in them. Which is alright, because I love these books.

But sometimes these books wear me down. Most of them are good but not great. They pass, like fads and fashions. Nevertheless there are a lot of them, and keeping current means slogging your way through a lot. For a slow reader like myself, there’s a sense that much of it isn’t worth my time. There’s continued pressure from authors and publicists to laud a book I was indifferent to. There’s pressure from communities to read books or blocks of books in order to participate in the public conversation, regardless of if they hold any individual interest. You need to know everything this year, but if you’ve forgotten it all by next year that’s alright. These books feel transient.

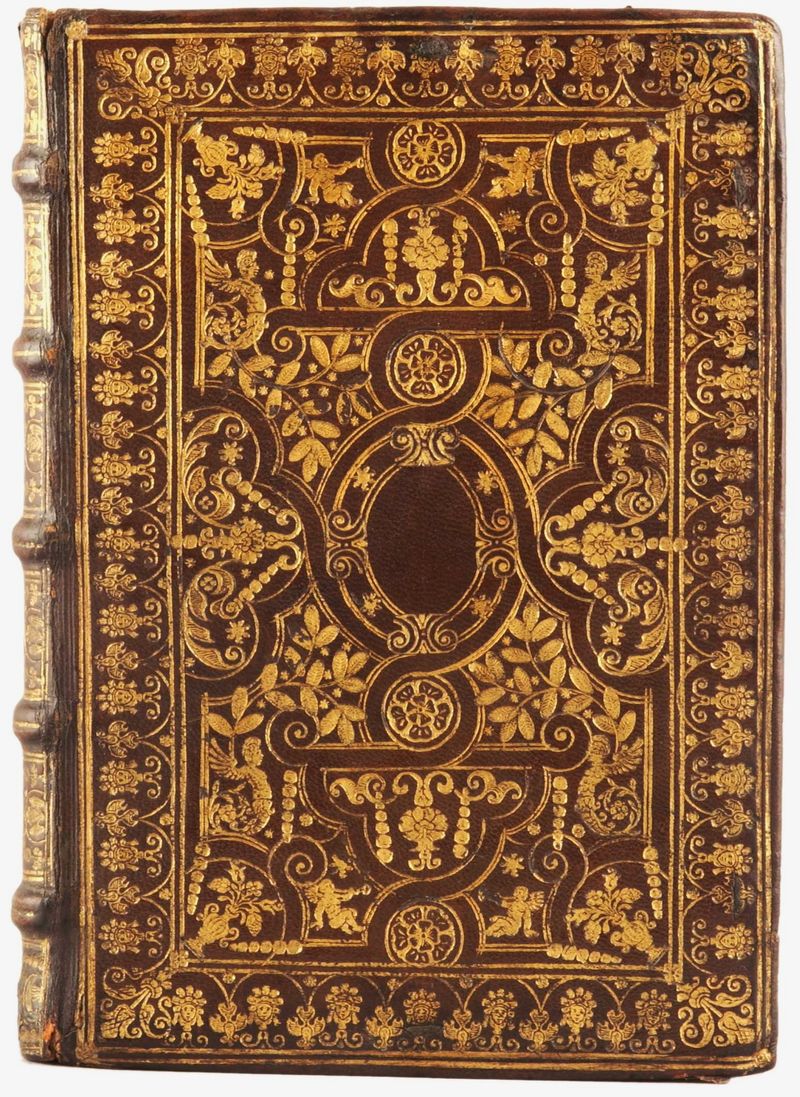

The other hand holds books, the timeless guardians of knowledge. These are the books I study, read, and collect. Nobody living is in any hurry to claim these as their product. They can be found in attics and libraries, garage sales and boxes on the street corner. It’s not always immediately evident what they are, where they came from, and what secrets they might hold. Decoding them and identifying them sometimes takes a lot of knowledge and research. But they are unique and surprising, often beautifully crafted. You might be the only person you ever meet who has the pleasure of enjoying any one of them. Reading them and knowing them puts you in the company of the giants of Western civilization. They are also professionally useful, bookselling to academics as I do. I’m rarely as happy as I am browsing the hushed booths of an antiquarian bookfair. These are the books of my dreams, and I adore them.

But then, these books are often remote and inaccessible. Those that aren’t held close to the chest in libraries can be prohibitively expensive. Even where easily acquired, these books need specialized knowledge, research and hard work, sometimes, to identify and even read. Communities of like-minded readers and collectors are hard to find, competitive, and sometimes hostile. People who do not share your mania will find discussions of books like these inaccessible and most likely boring. Professions specializing in books like these are scarce, hard to break into, and quickly becoming obsolete. Engaging with these books is lonely business.

But then, these books are often remote and inaccessible. Those that aren’t held close to the chest in libraries can be prohibitively expensive. Even where easily acquired, these books need specialized knowledge, research and hard work, sometimes, to identify and even read. Communities of like-minded readers and collectors are hard to find, competitive, and sometimes hostile. People who do not share your mania will find discussions of books like these inaccessible and most likely boring. Professions specializing in books like these are scarce, hard to break into, and quickly becoming obsolete. Engaging with these books is lonely business.

Anyone who thinks these two loves have anything at all in common is kidding themselves. People who love books and people who love books rarely overlap or have anything to say to each other. Yet, look. The Private Library featured this week a short introduction to Fanfare bindings. How could any warm body deny how beautiful these are? Or, meanwhile, even the driest academic or bibliographer gets excited once or twice a year when the latest Parker novel by Richard Stark is released, or in a year some massively deserving body like Hilary Mantel wins the Booker. I really wish there was much more overlap between these two worlds. I would love to see contemporary publishing publish less and take more care with the books they produce, drawing more from history and less from fashion when picking and producing their goods. Academic and antiquarian readers, meanwhile, have got to get with the program and make better use of social media and communities to spread and share knowledge about and enthusiasm for their object of interest.

I shouldn’t feel quite so two-headed when enthusing about one book or another. They are all books, right? Haven’t we got some more common ground?

November 19, 2010

It isn’t just *books* I hoard…

Aren’t those adorable? They’re Book Darts from Lee Valley Tools. I’ve been feeling under the weather for the last week or so; nausea, mostly, which has been making novel-reading a bit of a challenge. But like so many I’m a compulsive reader anyway, and this week I’ve been reading all the silly Christmas catalogues that have been coming to the house.

My dad does all his shopping at Lee Valley so I have every reason to suspect there are Book Darts on my horizon, which would be amazing because I am an obsessive acquirer and user of book marks. I always leave a bookmark in a book I’ve finished reading, as a means of marking it “read” – as well as a way of dating when I read it. This creates a need for infinite “disposable” bookmarks in the house (most often our Bob Miller Book Room beauties). Every time there’s a Small Press Book Fair or a Word on the Street I come away with a bag almost entirely filled with bookmarks. And they get used.

This doesn’t stop me from also acquiring quite a lot of good, reusable bookmarks. One of my favourites is from the Osborne Collection, a reproduction of the beautiful gilt-on-blue spine of The Book of Romance (image somewhat shamefully stolen from elsewhere on the internet). My boss once gifted me a bookmark featuring a monogrammed “C”, from Italy. As silly as it sounds I replace these bookmarks with a disposable one once I’ve finished a book. They also only get used for particular, appropriate books. I should get a prize for attention to detail – or maybe I should be institutionalized; whichever. My Italian “C” last saw use in the new translation of Orlando Furioso; the Book of Romance accompanied me through all three of Dumas’s Valois Romances.

This doesn’t stop me from also acquiring quite a lot of good, reusable bookmarks. One of my favourites is from the Osborne Collection, a reproduction of the beautiful gilt-on-blue spine of The Book of Romance (image somewhat shamefully stolen from elsewhere on the internet). My boss once gifted me a bookmark featuring a monogrammed “C”, from Italy. As silly as it sounds I replace these bookmarks with a disposable one once I’ve finished a book. They also only get used for particular, appropriate books. I should get a prize for attention to detail – or maybe I should be institutionalized; whichever. My Italian “C” last saw use in the new translation of Orlando Furioso; the Book of Romance accompanied me through all three of Dumas’s Valois Romances.

For Canadian books I use promo book marks for… Canadian books. I just used The Workhorsery‘s (lovely) promotional bookmark for Wilson’s Julian Comstock, and you know what? Having Workhorsery’s mission statement staring at me during all my reading for a week and a half actually did the promotional trick. I’m now so intrigued by them (and encouraged by their recent signing with LitDist for distribution) that I have every intention of buying both their books at the next Small Press Book Fair. It’s at the top of my shopping list.

I once wanted to do a study of early bookmarks, a topic which falls under “ephemera” in book history. It never came to be, which is unfortunate because I’d turned up some unusually marked-books in my rummagings. There seems to be something more personal, sometimes, in how readers choose to mark, tag, annotate and adorn their books. I’d love to hear your own bookmark habits! Have a favourite? Avoid them entirely? Any – dare I ask – dog-earers out there?

Happy friday!

November 15, 2010

A Tour Around My Library

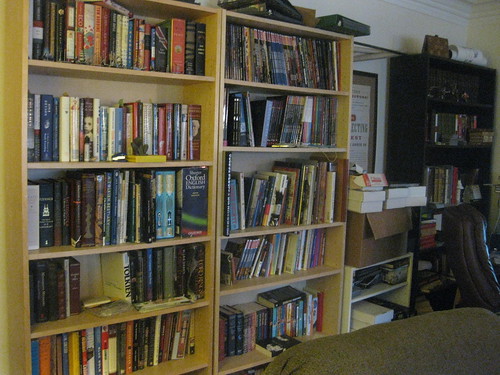

I’ve been tinkering with LibraryThing this morning because it strikes me as a tool made for people like me. Actually, I got an email almost exactly a year ago from Library Thing’s founder Tim Spalding offering to move heaven and earth to get me to use the service, so apparently I’m not the only one who thinks it’s the Tool For Me. After a couple hours of data entry and flailing, however, I am bewildered. I’m still not clear what I should be doing with it. I thought once I had all my books listed some kind of use or purpose might become clear, but when I ran into the 200-book limit of the free account I gave up and bailed.

Even the few books listed so far look wrong to me, like books I don’t own with only the most symbolic relevance to my actual shelves. I’m sure this is something that can be fixed with effort as I clean up ISBNs and covers, but there’s more to it than that. I think my “collection” might be too much of a mess to catalogue like this, or maybe just my collecting habits (which do, yes, run towards hoarding). Certainly my shelving and sorting regime is eccentric. It isn’t messy (well, okay, it is) or disorganized, in fact I’ve got every last book shelves exactly where I want it. Sub-collections, groupings and pairings mean a lot to me. But there’s a gradient, a volatility, a flexibility I enjoy that makes labeling difficult. I moved three months ago from a place I’d lived in for five solid years to a bigger, much more book-friendly space. To this day I have not unpacked several boxes of books because I can’t decide where to put them. Until exactly the right placing presents itself, I’d sooner keep them in boxes.

But enough of the words. If the internet has taught us nothing else, it has revealed that bookshelves are better seen than described. Mine aren’t works of art (I’m aesthetically and artistically barren), but I feel they explain my collection better than LibraryThing can.

This is a typical Charlotte’s Book Shelf. A disaster, yes. But look closer.

Canadian Literature, Trade Paperback (Partial)

In fact, the shelf houses several sub-collections. The top is Old Valuable Books of No Particular Subject (including a 6-volume Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen and a 1st edition Once and Future King by T.H. White in dust jacket). Next, pictured here (left), is Canadian Literature, Trade Paperbacks – which is to say, minus hardcovers and mass market editions (which are grouped elsewhere). Below that we have Contemporary Literature, Trade Paperbacks stacked in front of (and quite obscuring) Literary Non-Fiction, Paperbacks (below). Are you still with me? Good.

Contemporary Literature, Trade Paperback, Partial

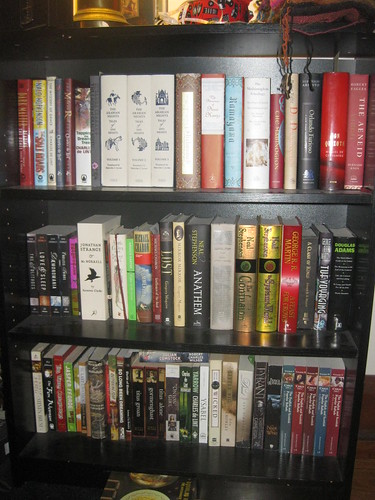

Further ’round the room things got more complicated. I have one entire bookcase devoted to hardcovers, and I’m still not clear exactly how to order them, so I went with the unusual tactic of shelving by preference. That is, my Favourite Hardcover Novels are on top, followed by my Favourite Hardcover Non-Fiction Titles (including my becoming-unwieldy sub-collection of Robertson Davies reference works). Below that we have Assorted Books On Magic Which Are Too Big To Shelve Alsewhere (including Plato’s Complete Works and a Shorter Oxford English Dictionary – not strictly books on the occult, but if you think creatively enough it fits), and taller pieces of my husband’s Tolkien collection, which continues on the next shelf.

A note on my husband’s books: he doesn’t have many. When we started dating I made it clear I was a book collector, but I don’t think he realized he the gravity of the situation until we moved in together and he found he was moving into a library. Whatever impulses he might have had to buy books were quickly and firmly quashed by pragmatism. Who needs to buy books when you live in a library? It would be cheaper this way. To his credit, he has not (yet) become a spouse who demands the collection be culled. Much.

My collection of Alexandre Dumas is actually much less well-ordered than you’d think. It had the misfortune of being unloaded next to the computer, and next-to-the-computer detritus inevitably joined my little Musketeers and Cardinal’s Men up there.

The Young Adult Literature, on the other hand, came together just fine. Of course, half of it seems to be missing. What does this say about my friends and family that this is what is most frequently borrowed from my shelves?

I am a big one for “prioritizing” my books. Not, like a smart lady, in terms of “read” and “unread”, but in terms of “to be shown off” and “to be hidden”. I acquire quite a lot of free books in the form of damaged discards, promos and garage sale finds which I take without discrimination, reasoning that I might need them some day, or you never know when something will come in handy. On the other hand, I don’t really want to display copies of, say, Atlas Shrugged, beat up old editions of Augustine and Defoe, Environmental Studies textbooks, or somewhat dogmatic analyses of current events like It’s the Crude, Dude or God Is Not Great. These go on bottom shelves, or are hidden in my bedroom.

But, find an empty bookshelf and find some books to fill it – if my house were a bookstore, we’d also call this “overstock”. So much of this stuff is books I just don’t know what to do with. In a fit of frustration, I started shelving these by publisher. I also discovered, to my dismay, that I have no fewer than three full shelves of back-issues of magazines – old Walruses and National Geographics mainly – things which shelve poorly and were relegated to the Shelves of Shame for their lack of spine. Sadly, this is also where my old, beat-up mass market Canadian books are. Not that they are objects of shame, but mass market editions fit poorly onto Billy bookshelves, which offer so much vertical space that they’re best filled with the taller trade paperbacks and hardcovers.

Ah, the office. Moving into the new house we harboured a fantasy that we’d have time to lock ourselves away and work on our respective intellectual pursuits. Ha! Maybe in another two years, when the 2-year-old doesn’t regard a closed door as a mortal offense. Still, I like to think my Book History collection and my husband’s Philosophy books look nice all together.

Now don’t be misled by all the empty space. I’ve boxes and boxes of books left to unpack – but I’m paralyzed with indecision right now. I don’t know where to put my piles of mass market fantasy books – they can’t very well be shelved next to Philosophy or in the the Nabokov. And surely there’s a better use of my office shelves than unloading the remaining damaged and garage-saled miscellany into it? And I tell you I don’t know where I’m going to put this 3-Volume Autobiography of Mark Twain when I get it home – it needs a shelf unto itself.

Anyway, it’s not all a giant mess. I have at least one nice, reasonably well-organized shelf. I’d better not add anything to the collection though, I’m plum out of space.

I’ve been working on a collection on The Intellectual Roots of Speculative Fiction, and this is much of it. Myths, legends, epics, retellings and early fantasies – these go here. As more arrive the contemporary genre titles get shuffled away (into oblivion – they don’t have a home yet). That’s the way of my sorting. Placeholders, like-titles, reclassified as space requires. There’s no hard-and-fast rules. I keep Crowley’s Little, Big with this History of Fantasy stuff, along side Lord Dunsany and The Worm Ouroboros. But Nalo Hopkinson and Charles de Lint will have to move on eventually – exactly why I couldn’t tell you, but they don’t belong, just yet.

I tired to denote this with overlapping categories on Library Thing, but every time I moved a book I felt pressure to change all the categories. With several thousand titles, I think this could start to become ridiculous. So I’m out, Library Thing. I tried. I’m either too organized or not organized enough for you! But thank you, and I will enjoy browsing other peoples’ libraries for the time being.

Oh, and if you’re curious – you can view my minimal Library Thing profile here. Maybe you can spot what I’m doing wrong? Meanwhile, I hope you enjoyed my more meandering tour!

November 9, 2010

A Quick Plug & My Thanks

One of my new favourite publishers is Seagull Books, the publishing-wing (pardon the pun) of the India-based Seagull Foundation for the Arts. These books have recently become available in North America via the University of Chicago Press, and each and every one of them that I have seen has been a thing of beauty.

They publish mainly on “the arts”, but within that cachet are a great many profoundly important thinkers. Among their published authors are heavyweights Adorno, Baudrillard, Todorov and Antonin Artaud. The books feature beautifully designed covers, heavy decorative endpapers, dust jackets of odd materials and good paper stock. They come in a plastic slip ensuring your book looks fresh off the press at the moment you buy them.

I’ve held off recommending them until now because the books did, however, have one (or possibly two) major drawbacks: many of the volumes use a heavy, coarse black material for the endpapers which reeks and stains. The first thing you’ll notice when you pull the book out of the plastic is an overwhelming chemical smell. The next thing you’ll notice is that the black “paper” feels as if it’s rubbing off on your hands. Over time the smell does dissipate, but the paper (and this might be the fault of the book’s paper too, not just the endpapers) bulks and warps, and the book will never again lie flat. Perhaps this was the early function of the plastic cover: to keep the book book-shaped.

BUT. I am thrilled to observe that the latest printing of Baudrillard’s Why Hasn’t Everything Disappeared? has addressed these problems. The black endpapers are gone, replaced by a nice textured beige material which doesn’t stink at all. The book opens and closes more easily, indicating that the paper might not be as stubborn. Everything that was good remains while all that was offensive is gone. Form seems to have caught up with function and now I am pleased to encourage you to seek these books out at your local bookstore, even if only to look at what a beautiful book can look like.