April 4, 2014

How To Get My Money – Periodical Edition

I read a lot of periodicals. I have subscriptions to fifteen magazines or journals, and buy individual issues of countless others. I try to at least look at each one, even if I don’t always read them cover to cover. I feel as if I might have some grounds for talking a bit about why people might read your publication, and why people might not.

Here is a step by step guide to how I will approach your publication, as a reader; what will convince me to read and what will drive me away.

A shiny new ‘zine appears!

Yay! I click through to the website. Oooh, looks interesting.

Can I buy an issue to read on my ereader?

If I can, I will buy it right away. I might hesitate if the only retailer is Amazon, Kobo, Barnes and Noble or some other giant. If it’s direct, Weightless Books or Gumroad, I won’t even stop to think. I will BUY. I will read! Horray!

Can I subscribe to an e-edition?

If the ‘zine has a good track record or speaks directly to my soul, I will subscribe without too much thought. After all, I spend $20 on a book, why would I balk at spending the same amount of money to get 4-12 issues emailed directly to me? I love esubscriptions. This is why I have six of them.

Can I buy a paper copy?

Okay, so not everyone is putting together digital ‘zines. That’s cool. I like paper better anyway. I will buy physical copies if the total cost of the issue plus shipping is under $20. I will likely subscribe if it is something I really love. I love mail. This is why I have nine physical subscriptions.

Does it have an awesome mobile site?

Once I cannot buy an issue or subscription for comfortable reading, things get tricky. I used to read on my phone, but this resulted in a rapid decline of my eyesight, headaches, and general discomfort. I can read in short bursts, but I will not curl up with an issue on my phone.

If I have to read something on my phone, it had better be optimized for mobile reading. The text size has to be big enough, or adjustable. The menus must be simple. There can’t be ads or flash graphics reloading things every thirty seconds. Preferably, the text should take up the entire screen, so I don’t have to zoom (and end up with scrolling issues).

Some ‘zines have got perfectly serviceable mobile reading experiences (Apex Magazine and Ideomancer do good jobs). I tend to open these ‘zines in web browsers and leave them there for weeks. Maybe I will get to them, maybe I won’t.

Do I have to read it on an old-school website?

I probably won’t read. It’s too hard. It’s uncomfortable. I will only bother if a specific story has been recommended to me so many times that I can’t look away.

I mean, I get it. It’s free. You’re all working for free. But it is because it is free that I’m not as likely to read if you make it hard for me. I paid for my other magazines. I’m invested. Given the choice between reading something that hurts my eyes online, and reading something I paid for on my Kobo, I will do the latter every time. And I do have to choose – 15 subscriptions, after all. I can’t read everything.

A quick note on Kickstarters:

I acquired a large number of my subscriptions through Kickstarter. If you are running a Kickstarter for your periodical, it is an early subscription campaign. If you are running a Kickstarter for a periodical and your core tier is not “SUBSCRIPTION”, then you are doing it wrong. Any Kickstarter campaign, whatever it is for, should sell, fundamentally, the thing you are making. Probably for cheap, like an early bird special. It is dead easy for a supporter to see that $15-$20 tier and say, yah, I’ll throw you a twenty. And I get a subscription, which would cost me $22 if I waited! Good deal! This is where most of your supporters will lie. Your subscribers too. You will have contact with these supporters for the rest of the year. They are your core constituants.

Tiers full of postcards, prints, signed books, Tuckerizations, critiques… these are cool, but this isn’t what you are selling. This is the extra stuff, the honey that sweetens the pot of Zine Tea. If I have to pay ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS to get the equivalent of a subscription, you have missed the point. I want to love your product. It looks like a cool product. Please sell your product.

A quick note on free ‘zines who do everything right:

You produce a great product, you make ezine subscriptions available and you do it all for free. You are AMAZING. But I still want to give you my money, and you are making it hard by giving it all away. I know, I could just click the PayPal button. I probably won’t. I will procrastinate. I will think, “I should throw some money in the tip jar some day.” I won’t get around to it.

It takes very little “extra” to get me to pay in. Release the paid material a week ahead of the free edition, as Beneath Ceaseless Skies does. Maybe include an extra story in the e-edition. Send me a t-shirt, I don’t know. But do something to fish for that money. You might think you don’t want it, but you do. Give it all to your featured author if you feel bad pocketing it. Buy your slushies Starbucks gift cards. But do take the offered money and put it to work. If you don’t, somebody else will, and that person might not be as awesome as you.

So, how about you? What makes you read a ‘zine? Leave a comment even just to say hi!

February 6, 2014

Want to be a Bookseller for a Day?

There is some excellent discussion over at E. Catherine Tobler’s blog about reading women, something we should all be doing more. There is nothing new under the sun: this issue comes up all the time (as it should), and in particular I remember the furor that followed this article in the Guardian three years ago. We all swore up and down to read more women, and some excellent people swore to read only women to make up for it.

Do we? Well. A cursory look at my most recent reads on Goodreads reveals I’m sitting at about 50%, which is good, but I still feel disconnected. I force myself to read a lot of women when I am reading “good for me” books. Capital-L Literature. I need to read George Eliot just as badly as I need to read Thomas Hardy. But when people ask me who I love best? Those writers I will reach for each and every time I can? All men. Eco, Dumas, Stephenson, Chabon, Murakami. My favourite books are all written by men. Tolstoy, Peake, Herbert, Heller. I am a terrible cheerleader for women’s writing.

But this wasn’t always the case. When I was deep into reading fantasy and mythic fiction in the late 90s and early ’00s, every single book I loved was by a woman.

Every. Single. One.

What happened? How did I fail to keep up? Now, ten, fifteen years later, I don’t know who else came up to join the women whose writing I once loved. A lot of the women I used to read have retired, vanished, or died. The new generation seems to be writing YA. I am tired of reading about teenagers.

So I put this to the crowd. I have made a list below of the books I loved as a young woman. Can you recommend anything to me that I might love now? I hardly remember the books, aside from that I loved them – and it is possible that my tastes have matured and changed. That might explain why, for example, I feel such a strong attraction to alt historical novels, and yet I hated Naomi Novik’s His Majesty’s Dragon. Maybe I have moved on? Or maybe not. Try me.

The Mabinogion Tetralogy by Evangeline Walton

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

The Wood Wife by Terri Windling

Tam Lin by Pamela Dean

The Fox Woman by Kij Johnson

The Innamorati by Midori Snyder

The Stars Dispose by Michaela Roessner

The Moon and the Sun by Vonda McIntyre

The Death of the Necromancer by Martha Wells

The Shadow of Albion by Andre Norton & Rosemary Edghill

January 4, 2013

On Literature and Fandom

When Jim Zubkavich, the Toronto-based creator of the comic Skullkickers, posted this plea to fans to support creator-controlled comics, it got me thinking about the new realities of publishing.

Making money as a content-creator, be that content comics or words, has always been tough, and these days writers are left mostly on their own to make that money. It’s becoming increasingly unlikely that any writer, even an established, mid-career author, will be signed to a multiple-book deal that allows them some time and space to hone their craft and develop a body of work with the financial support of a publishing house. Journalists are all freelancers, living cheque to cheque, when they can extort the money from their clients. Even writers who have sold their books are expected to do a lot of their own publicity and marketing. A writer (or comic creator) is pretty much exclusively responsible for every dollar they make. Which sounds reasonable when you put it like that, but this is a fairly new situation. There’s no security net in creative content generation.

This direct interface with customers can work very well for the creator. A hundred self-publishing gurus will tell you that self-publishing will make you rich, quick. You get a bigger share of the pie, and you have greater creative control. You can look at Indigogo and Kickstarter and see a huge number of successful, funded projects. Ryan North and Kate Beaton have raised over half a million dollars for their new book, a choose-your-own adventure take on Hamlet called To Be or Not To Be. Less spectacularly, over the holidays I bought into J. Torres’ anthology True Patriot. Comic creators have made very successful use of these platforms to finance their creative careers – can authors do the same? And would they want to?

Some supporters of self-publishing don’t understand why every established author hasn’t just jumped ship to publish their own work. There are still a lot of good reasons to stick with a publishing house, like the services they offer in editing, publicity, design, and just plain handing “the business end” that can be so baffling to creative types. But I think there’s more to it than that. Most literary writers don’t actually have the fan base – “the data” – to support a go alone. In other words, they don’t actually pay their way.

When Rich Burlew of the webcomic Order of the Stick smashed open the crowdfunding box by raising $1.2 million to reprint back volumes of his work, he explained in an interview that he found approximately 1 in 50 of his readers was willing to put money into his venture. A friend of mine moderated a panel on crowdfunding novels which discussed a very similar guesstimate: The Thousand True Fans Theory, which states that in order to successfully fund something you need 1000 “true fans”, people willing to buy anything you produce, and these people can be expected to spend one day’s wage on your goods.

Kate Beaton, Ryan North and Rich Burlew have these followings: they have fandoms, not just readers. People who are dedicated to their brand and will buy anything – anything – they produce. Can writers mimic their crowdfunding success? Sure, the writers with fandoms. I bet if Neil Gaiman Kickstarted a book he’d have eleventy-zillion dollars in 24 hours.

Do literary writers have fandoms? I think this is an untested question. I’m inclined to say no – literary readers seem less brand-loyal, so to speak. They want each work to win them over anew. Loyalty seems to be to the work, not the creator. Services like Goodreads and Wattpad let users “fan” writers they admire, and the numbers attributed to even “successful” literary writers are dismal. Vincent Lam, winner of the Giller prize for his debut collection, Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures, has 18 fans on Goodreads, 202 on Wattpad. By comparison, Paul Coelho has about 14,500 fans on Goodreads and 2,700 on Wattpad. Using the Theory of a Thousand Fans, Vincent Lam would be lucky to sell one book.

Could this be turned around, and should we care if it can’t? I’m inclined to think that even if an author hustles their little bum off, they won’t see numbers like Rowling, Gaiman, or even Coelho can post. They could hire a stylist and a media manager, but that will only go so far. I think there is some success to be had by establishing a social platform for literary readers – something like the 49th Shelf, if they had a “fan” button. But, as a literary reader, I can say I’d probably run around fanning everyone, and that would amount to a lot of goodwill but maybe not a willingness to buy everything.

Part of what alarms me about publishing according to “data” and sales is that I think some things are worth putting to press despite their commercial viability. Be it a promising writer who needs time to develop, or a work which simply deserves to be saved for posterity or academia, regardless of how the unwashed hoards like it. If we only made popular art, we’d be a civilization of cretins in no time. But who will be the altruistic philanthropist that supports non-commercial literature? The government? Random House? Need writers seek out patrons again?

I believe this is the direction of things, so ultimately time will tell. Good luck, writers!

November 26, 2012

On Anna Karenina In All Forms

Director Joe Wright has just released his Anna Karenina, a film based on the opera based on Tolstoy’s book. Wait – there wasn’t an opera? Well, there is now. And it’s bloody fantastic. This is big, overwrought Romance done up exactly right for the stage, and does its source material justice.

Director Joe Wright has just released his Anna Karenina, a film based on the opera based on Tolstoy’s book. Wait – there wasn’t an opera? Well, there is now. And it’s bloody fantastic. This is big, overwrought Romance done up exactly right for the stage, and does its source material justice.

I do love Tolstoy to a more-than-usual degree but it wasn’t that hero-worship that made this movie for me: for once, it was the film interpretation’s departure from the source material. Tolstoy is, generally speaking, Jane Austen filled with disagreeable men arguing about philosophy. It’s a formula aimed at my heart. I love Jane Austen, I love disagreeable men, and I love arguing about philosophy. Tolstoy’s best heroes are his grumpy little outsiders, more concerned with their moral development than the high drama going on around them: War and Peace‘s Pierre and Anna‘s Levin. The high drama seems to be there as a feint. One might think War and Peace is about Prince Andrei and Natasha Rostov or that Anna Karenina is about Anna Karenina & Alexei Vronsky – but they aren’t, not really. By the end of the books the romantic leads are long dead and there sit Pierre and Levin contemplating peasants and making babies.

Which is wonderful, but opera is about melodrama and so Wright’s Anna Karenina has sided with the Jane Austen and dispensed with the disagreeable philosophers. Levin still makes an appearance, but his story seems to be a cute side-plot to soften, a little, the doomed tragedy that Anna & Vronsky endure. An opera about hiding away on your country retreat writing a treatise on farming, while agonizing over your inability to properly tend to your cows because of your new baby would be very dull indeed. The film chooses instead to cut right to the hair-tearing and the horse racing. The drug addiction and the suicide.

The film is not all scandals, though. Wright does an excellent job of making Anna out to be, not likable, exactly, but right. All through the book women are made to endure hardships and are made to feel that they, despite being the victims, are responsible still for the continued happiness and stability of the men to whom they are attached. They must forgive philandering, tolerate loveless marriages, wait on moody philosophers and accept public humiliation for the sake of their husbands and children. It’s grossly sexist and unfair from our modern standpoint.

Without hugely altering the source material, Wright shifts our sympathies. Oblonsky’s philandering is portrayed more foolishly and his wife Dolly is more aware of the wrong done to herself. In a scene not to be found in the book, Dolly confides to Anna that she wishes she’d been brave enough to do what Anna did. Anna herself is put into a tighter cage and even her rages and jealousies become understandable. Her suicide is an inevitable tragedy rather than an act of cruel vengeance. The film’s Karenin seems the most cognisant of the entire tragedy and paints for Anna explicitly what must be done to avoid a horrible outcome, and we understand through it how bad things are for the lovers due to the entirely unavoidable points of gender inequality. The book’s Karenin succumbs instead to some strange spiritualism that operates as a plot device and a reminder that Anna has sinned against a God or a fate.

Personally, I like and sympathize better with a woman trapped by unfair social conventions than one doomed by her unwillingness to conform to her proper place. This is a departure from the philosophical Tolstoy, but a welcome one.

Add to this refocused social commentary a brilliant script by Tom Stoppard and a beautifully choreographed staging with an operatic conceit and you have what I consider to be a fabulous film. The best news of all is, the book is also amazing and is still available. Those who want the disagreeable, philosophical parts as well have the supplementary material. The new movie lets readers like me have it both ways: a deep, philosophical book with the Romantic, tragic parts pulled out, set to music and painted on the screen. Is there anything else to ask?

November 12, 2012

University Press Week!

It’s University Press Week! This must be a new designation because in the past I have honoured university press books in a haphazard way, apparently at the wrong time of year. My efforts to get some Canadian university press books on the Canada Reads longlist was a sad failure, but those savvy folk at the Association of American University Presses have brought this one down in time for Christmas shopping. I have more than my share of opinions about what you should gift your loved ones with this year, so with no further ado, I give you three amazing university press offerings sitting on shelves right now!

It’s University Press Week! This must be a new designation because in the past I have honoured university press books in a haphazard way, apparently at the wrong time of year. My efforts to get some Canadian university press books on the Canada Reads longlist was a sad failure, but those savvy folk at the Association of American University Presses have brought this one down in time for Christmas shopping. I have more than my share of opinions about what you should gift your loved ones with this year, so with no further ado, I give you three amazing university press offerings sitting on shelves right now!

Harvard University Press’s Jane Austen Annotated Editions

Emma is the third in Harvard University Press’s Annotated Jane Austen series, and every bit as beautiful as the previous publications of Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion. The whole oeuvre of Austen in these hardcovers would be magnificent on the shelf of any collector, but be warned that no paperbacks are currently forthcoming. These are lavishly illustrated editions beautifully assembled, and would barely hold together in a less sturdy format. But at $35-$40 each, who could complain anyway? Harvard, by the way, seems to be going whole-hog into these amazing annotated editions. An annotated Frankenstein also appeared on our shelves this fall, and is no less recommended.

Northwestern University Press’s World Classics Series

I think one of the greatest services university presses renders is in keeping lesser-known works of great literature in print in good, well-edited and produced editions. Northwestern University Press has a number of these series, but I have a special spot in my heart for the World Classics. They have editions of the poetry of Pushkin and Pasternak, a lovely new Divine Comedy of Dante and Rilke. Lesser known additions include Anne Seymore Damer, Ivan Shcheglov, Luigi Meneghello and Ilya Ilf. These books are paperbacks, but exceed Penguin Classics and Oxford World’s Classics in quality by a mile. If you like NYRB editions, you’d love these.

Yale University Press’s The Woman Reader

Of course, most of what university presses tend to publish are academic books. This doesn’t, however, mean inaccessible, specialist books. Belinda Jack’s The Woman Reader is what Yale considers a “trade” publication, but this is a step beyond “books for anyone”. It is a historical overview of how women read, and have read, over the ages and cultures complete with endnotes and citations. But the book is anything but dry: Jack’s prose is succinct, funny, and totally readable by the non-specialist. Yale has a great backlist of similarly academic-but-enjoyable books on books, including Andrew Pettegree’s The Book in the Renaissance, Margaret Willes’s Reading Matters and Alberto Manguel’s A Reader on Reading.

November 7, 2012

Hardly the Bottom of the Box: An Interview With JonArno Lawson

I practiced the poems from JonArno Lawson’s new children’s poetry collection for two days before meeting with him to talk about them. Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box is an absolute treat to recite, but as I’d discovered that first night reading aloud to my 4-year-old, putting the emphasis on the wrong syllable can result in an unrhythmic stumble and a loss of musicality. A well-rehearsed poem, on the other hand, dances off the tongue and tickles the ears. These were poems that rewarded a careful performance. Consider “Monkeys in the Dump”:

I practiced the poems from JonArno Lawson’s new children’s poetry collection for two days before meeting with him to talk about them. Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box is an absolute treat to recite, but as I’d discovered that first night reading aloud to my 4-year-old, putting the emphasis on the wrong syllable can result in an unrhythmic stumble and a loss of musicality. A well-rehearsed poem, on the other hand, dances off the tongue and tickles the ears. These were poems that rewarded a careful performance. Consider “Monkeys in the Dump”:

A clump of clumsy monkeys lumbered through the dump.

The clumsiest amongst them tumbled over in the junk-

it jumped and spun and tried to run but crumpled to its rump

then slunk away until it slumped into the muck, and sunk.

I was pleased when I mastered the performative aspect of Lawson’s poems, and surprised to discover that he himself doesn’t enjoy doing readings. It’s a question of temperament rather than a philosophical aversion, but nevertheless unexpected given Lawson’s emphasis on sound.

Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box is a collection of nonsense poems for the young (and young at heart) in the tradition of Dennis Lee and Dr. Seuss. Lawson starts his poems from sounds and builds with orality in mind. The results are clever and fun to read, and so it’s no wonder that he has found success as a children’s poet. He has won the Lion and the Unicorn Award for Excellence in North American Poetry twice (in 2007 and 2009), and has been short-listed for the Ruth and Sylvia Schwartz Children’s Book Award. He estimates he has published ten books so far, though his first two collections of adult poetry have recently been pulped by their publisher, Exile. It has been as a children’s poet that Lawson has found success, though there is nothing about his work which is facile or simple.

Every parent in the country reads poetry to their children, and yet as adults many of us seem to have lost the taste. What changes? Lawson suggests that as adults, we look down on rhythm and rhyming, which is at the core of what we offer to our children. “Adults can recite Dr. Seuss without thinking,” he points out, but we don’t think to look for the same qualities as adult readers. Could that gap be bridged? Perhaps, we agreed. “We could use the lessons from childhood to inform adult poetry.”

Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box is unquestionably a book with adult appeal. It is beautifully produced by Porcupine’s Quill on their distinctive Zephyr Antique paper and features 32 full-page paper-cut prints by Mexican-Canadian artist Alec Dempster. It was this pairing with Dempster that Lawson says sold the book to Porcupine’s Quill. Though Lawson had published A Voweller’s Bestiary with Porcupine’s Quill in 2008, they weren’t sure what to do with the poems that would become Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box. These poems were originally part of the manuscript that would become Kids Can Press‘s Think Again, but they were culled to give Think Again the narrative structure it has in its finished form. Alone the poems of Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box are cute, but alongside Dempster’s stark, surreal relief-cuts the book takes on a stranger, more macabre quality. “The Inksters like a challenge,” Lawson says of his publisher, and the Lawson-Dempster combo gave them an off-the-beaten-path project.

Indeed, life as a children’s poet seems to mean a lot of collaboration. Lawson’s children’s books have been illustrated by a variety of artists, including Voweller’s Bestiary, which he illustrated himself. Speaking of Dennis Lee & Frank Newfeld’s contentious collaborating relationship, Lawson concedes the classic illustrations for Alligator Pie were “Ugly, but unique,” but that it’s good for a poet to be pushed “outside his comfort zone.” He has generally had only a small amount of control over who illustrated his work and how. Dempster certainly seems to have had free reign with Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box, producing more work for the book than anyone thought he would. Lawson only met him a couple of times, including at the book’s launch. The artist and poet produced their contributions independently – but Lawson had faith in Porcupine’s direction, and seems pleased with the results.

As for the kids, I think they’d be pleased too. Lawson’s three children – aged 11, 8 & 4 as of this writing – provided input and inspiration for the work, and Lawson tells me they still read poetry willingly. My 4-year-old found the poems challenging initially, but after some practice on my part she warmed to them. The intended audience is likely the older child, but adults should pay attention too. The language is smart and flows beautifully. An emphasis on sound and rhyme ought to recommend it as much to the adult reader as to the younger. If you need a final selling point, just have a look at a physical copy. You’ll be loathe to relinquish it to the sticky and inexact care of your children! It’s a beautiful work in every sense, and highly recommended.

This review and interview based on a review copy courtesy of Porcupine’s Quill, and an enjoyable in-person chat with JonArno Lawson.

October 23, 2012

Book-Lover’s Guilt

In case you weren’t feeling glum enough about the imminent closure of the Toronto Women’s Bookstore, last night we got the news that Canada’s largest independent publisher, Douglas & McIntyre, has filed for bankruptcy.

The news brought a chorus of astonished gasps and moans from Twitter. Nobody likes to see things like this. Good, experienced publishing people could lose their jobs. Writers could lose their publishers. Their books could go out of print. Oh, and something about the cultural contribution too. Canadian culture, supporting our own, something something.

Of course, if everyone who was so sad to see them in straits actually spent money on their books, they might not be so bad off. That was the first thing I thought, in any case. Oh man, when was the last time I bought a Douglas & McIntyre book, anyway? The summer of 2010, Darwin’s Bastards, Zsuzsi Gardner? July 2010. Cigar Box Banjo, Paul Quarrington, for my husband’s birthday. November 2011, Something Fierce, Carmen Aguirre, for Canada Reads. That’s $80 in two years. No wonder they’re going out of business! Why didn’t I pick up Daniel O’Thunder, Lightning, The Book of Marvels when I saw them? And why didn’t I buy them all at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore?!

The fact is I can barely feed myself and my children, let alone every writer, publisher and bookseller in Canada. But that doesn’t prevent the lingering guilty feeling that I somehow should have tried.

My coworkers and I sit here scratching our heads this morning, wondering how this could have happened to D&M. They have a phenomenal list. We bring in – and sell – almost every single book they publish. What more must a publisher provide? Great, well made books that people want to buy. Isn’t that the formula? How can that fail to pay the bills?

Admittedly, I live in a bubble. Our bookstore sells books nobody else can manage to move. My customers are heavy readers who – bless them – never ask about the prices, just pay them. My friends are heavily educated and literate, with a strong sense of social responsibility when it comes to supporting the local. My 276 Twitter followers seem to be 200 authors, 75 publicists and my mom. The millions of people who buy and read 50 Shades of Grey? I don’t know who they are.

So maybe out there in the real world, D&M’s excellent books are going unnoticed. Maybe all the “buzz” the journalists, bloggers, reviewers and publicists claim to be out there is being generated by review copies and good intentions. I’m a bookseller and a blogger, after all. I have my share of books given to me, and what I buy I often buy at cost. Maybe I am to blame after all. Do we excuse ourselves from buying books because we feel our endorsement, our “word of mouth” is worth more than the $19.95 we’d spend on the book? I wonder sometimes. I don’t know how else to reconcile the contradiction I’m seeing. We all love and “support” these books, and yet the money isn’t there. Are the readers – the ones who don’t work for the publishing houses, who don’t get their copies for free – there? Are they reading our reviews and buying the books? Does buzz equal sales?

We’re troubled, this morning, about what this could all mean. If a Douglas & McIntyre can’t make it, I wonder if anyone can. Does a publisher need to be propped up by a mega-bestseller (and does a Canada Reads winner not suffice)?

May 26, 2012

Indiegogo, Kickstarter, Subscriptions and the Letterpress

I never quite understood why more Letterpresses and Private Presses don’t do more editions of popular works of literature. It seemed to me, from a new-book bookseller point of view, to be a no-brainer. Customers are forever asking me for “nice” editions of their favourite literary classics, and the texts themselves are open source. How much work can it possibly take to just choose, say, Pride and Prejudice as your next publication?

I never quite understood why more Letterpresses and Private Presses don’t do more editions of popular works of literature. It seemed to me, from a new-book bookseller point of view, to be a no-brainer. Customers are forever asking me for “nice” editions of their favourite literary classics, and the texts themselves are open source. How much work can it possibly take to just choose, say, Pride and Prejudice as your next publication?

Well here’s your number: About $20,000 worth of work. Vancouver’s Bowler Press has apparently been thinking what I’m thinking, and unlike me, the ignorant outsider, they know what the hurdle was. It’s all very well for me, a frontline bookseller, to identify a potential market, but it’s quite another thing for a craft bookmaker to find and connect with those customers, most of whom are not your usual Private Press fanatics. So you print a run of a “popular” text for a more mainstream audience – then what? How do you get them into the hands of those buyers?

Kickstarter, that’s how. Indiegogo. The internet seems to have finally come around the an idea that has, in fact, existed in publishing for centuries: the subscription model. You secure your buyers first, then print the work. The model never really went away – I bought an edition of John Crowley’s Little, Big by subscription a few years ago, and Subterranean Press has been printing numbered & lettered editions of George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire books for years, to name a couple of examples. But it seems to me that the ability of any given publisher’s ability to really connect with the potential subscribers hadn’t really come into it’s own before now.

A brief history. In the early 1830s an architect named Owen Jones decided to undertake a publishing venture, a full-colour guide to the Moorish palace, the Alhambra. At the time, printing technology was insufficiently sophisticated to really do the work justice, so Jones decided to basically invent (or perfect) a new printing technology for the job, chromolithography. Inventing a new technology and then mobilizing it to produce a book which would have, to say the least, a limited audience was going to be expensive work, so Jones appealed to subscribers to fund the project. This was a slow process. It took Jones more than ten years to get enough money to complete the project, eventually published as the 12-volume Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra.

A plate from Jones’s Alhambra.

Ten years. By comparison, Bowler Press is going to try to raise their $20,000 in a month and a half. If this works – and it should, if there is any justice in the universe – every Letterpress operator out there should pay close attention. In my humble opinion, this can work, regularly and consistently. I mean look at this: most of Bowler’s contributors aren’t even committing to buying the book itself, they’re buying the ephemera. More and more, regular folks are considering Kickstarter and Indiegogo legitimate shopping destinations. It is becoming more than just a rallying point for fans. I’d just love to see more projects like this out there (and not just because I have a budding Kickstarter problem). Please? It has worked before, and it should work again, better than ever.

March 30, 2012

My Response to David Mason – Huh?

I really do enjoy my subscription to Canadian Notes and Queries. It is probably my only periodical – outside of Chirp – which I happily renew every year without even having to consider it. I love Seth’s design work. I love the featured cartooning work. I love the often arch and argumentative nature of many of the essays. And I love that they give space to David Mason, really the only space in any Canadian periodical given to an antiquarian book dealer. But,

I really do enjoy my subscription to Canadian Notes and Queries. It is probably my only periodical – outside of Chirp – which I happily renew every year without even having to consider it. I love Seth’s design work. I love the featured cartooning work. I love the often arch and argumentative nature of many of the essays. And I love that they give space to David Mason, really the only space in any Canadian periodical given to an antiquarian book dealer. But,

Dear Mr. Mason,

You lost me with your latest contribution, “Secrets of the Book Trade: Number 1“. I sorrily admit I didn’t understand a word of it. I followed you as far as the admission that antiquarian booksellers are snobs – agreed, and good for you! – but the following generalizations about trade bookselling sounded outright made up.

Which booksellers, pray tell, were you referring to? I’m not sure if you’ve looked around lately, but there aren’t a lot of trade booksellers left, and those still standing don’t bear any resemblance whatsoever to the characture you’ve drawn. “…what they are lacking is knowledge of about 500 years of the history of their trade.”? “new booksellers share with publishers is a certain distrust – even fear – of antiquarian booksellers”? “You order a bunch of books from a catalogue, provided by a publisher, sell what you can and return what you can’t. No risk, no penalty, if your opinion of what might sell is wrong.”???

The above quotes represent three total untruths about trade bookselling featured in your essay.

Just this week Ben McNally delivered the 2012 Katz Lecture at the Thomas Fisher on the topic of Is There a Future (Or Even a Present) for Bookselling? which included a learned history of the book trade. Yesterday I attended new book creator Andrew Steeves‘ lecture on “The Ecology of the Book” which also consisted, largely, of a history of the book trade. Even I am a new book seller and a book historian, not to mention an antiquarian book lover and collector. The booksellers I know – those who remain – are very knowledgeable people who are in no way the peddlers of pap you seem to be describing. I think you and I can agree that Chapters/Indigo is not staffed by “booksellers” so let’s leave out their lack of participation in the larger world of books – unless it was actually that straw man you meant to burn down, in which case I’d feel better if you’d been a little more clear.

We bear the antiquarian trade no ill-will. In fact we continue to foster relationships with used and rare sellers. Our remainder tables continue to be pillaged by scouts and dealers, and we offer deep discounts to some favoured dealers who will take away our overstock by the box. We know that the antiquarian dealers do us the same service we do them – redirecting customers who erroneously visit one or the other of us in search of “nice copies of…” or “cheap copies of…”. I send my customers to you weekly. I hope you do us the same courtesy.

As to this business of publishers’ returns policies giving us a free pass… well, perhaps it is this which stuck in my craw the worst, as I hear it again and again from everyone, customers, academics, and now you, who should know better. The ability to return a limited quantity of books allows us nothing but the merest bit of breathing space. We have to remainder or toss books too. We have to vet the vast, vast floods of new books which are solicited each year into a good, salable collection of which we can return no more than 15% and, even then, which we often have to return at great cost to ourselves in shipping and brokerage – especially brokerage. Choosing which books will sell requires not just an intimate knowledge of every author, publisher and subject we cover, but of our customers and their interests, price points, and whims. Every book we buy is a gamble. Unlike you, who can pick up certain Modern Firsts at a good price without having to think about it, we have to speculate on the market of every book which comes through the door. And we can only be wrong 10-15% of the time.

Further, if we feel a social responsibility to pick up and flog new, upcoming authors and presses with no existing market whatsoever in the name of encouraging local talent and the potential cultural giants of tomorrow, we do so by the grace of this returns policy. Not that we send books back to small and independent publishers – quite the contrary, we have a policy of keeping these books whether they sell or not, out of respect for the limited resources of their publishers. But we can do it because of the returns to larger publishers who can afford it, which will let us free up some cash for zero-gain experiments.

I cannot imagine what point you will eventually make with Number 2 of this series after making such an artificial distinction between booksellers in Number 1. If your intention was merely to point out how very learned you are, I salute you but suggest that you do not become more learned by painting us as less learned. I’d like to suggest that a more useful project might be to make common cause against the real outsider in our field, the entirely algorithm-based online bookseller who is undermining both our businesses by selling entirely unvetted, undifferentiated texts based on price point alone. But that’s another post.

In conclusion, I think you’ll find those booksellers among us who remain in business in this difficult age are a hardy bunch, creamier than whatever booksellers of yesteryear you’re remembering. We each have our bodies of knowledge about aspects of the objects we dedicate our lives to. We are aware of how we compliment each other – have we kissed and made up yet?

Thanks for you time,

Charlotte Ashley

P.S. I would love and prefer a job in antiquarian bookselling. If you’re ever looking for a knowledgeable and neurotically dedicated apprentice, you just let me know.

March 7, 2012

I <3 the Shahnameh

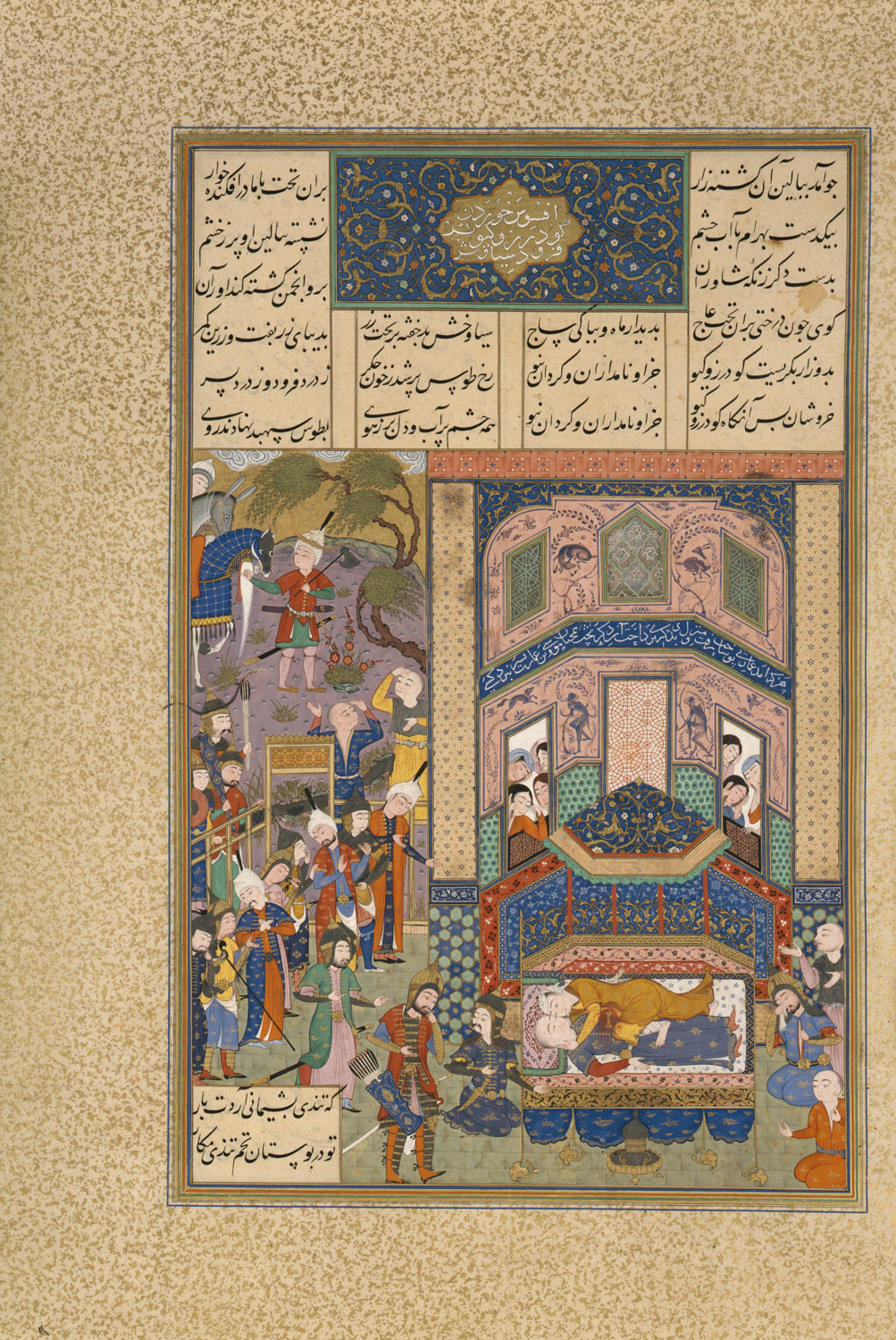

In his 2003 A Splendor of Letters: The Permanence of Books in an Impermanent World, Nicholas Basbanes tells the memorable and, speaking as a bibliophile, devastating story of the Houghton Shahnameh.

The story goes like this: Arthur A. Houghton Jr., a 20th-century American book collector, has among his insanely valuable books a manuscript which has been described as the most spectacular example of Islamic art, if not of manuscript art, ever produced: The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. This copy of the Shahnameh (a 50,000 line poem first put to paper in 1010 by the Persian poet Ferdowsi) managed to survive intact from its creation in the early 16th century until the 1970s, when it ran afoul of Houghton.

Houghton acquired the manuscript from Baron Edmond de Rothschild in 1959 and almost immediately put it on deposit at Harvard University with “the understanding that an elegant facsimile would be published by the university’s academic press.” (Basbanes 2003) Then, for whatever reason, he abruptly withdrew it from Harvard in 1972 and donated 78 of the most valued pages to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yes, he cut out seventy-eight pages and gave them away.

There’s some speculation that Houghton intended to eventually donate the rest of the manuscript to the Metropolitan Museum, but that didn’t happen either. Instead, between 1972 and 1996 the remaining 180 pages of the manuscript were sold off or traded, in batches both by Houghton and later his estate, to a variety of private and public collections. Souren Melikian wrote in his 1996 report on the final Sotheby’s sale “It was a great day for commerce but hardly for the preservation of cultural treasures.”

Long story short, a priceless treasure of book art was destroyed by a single owner. But all was not entirely lost: in 1981 Harvard University Press did manage to produce a facsimile in two volumes, 600 copies of which were actually sold to the public. Nowadays you can get a copy of this facsimile for the comparatively low price of $3500-$4500.

Ever since reading Basbanes’ tale in 2003 I have been mad to own a copy of this facsimile. It was absolutely in my top-5 list of books I’d buy if I, you know, had the resources to spend on collecting that I wish I did (along with Frank Wild Reed’s Bibliography of Alexandre Dumas and the 1893 deluxe edition of the Beardsley-illustrated Morte D’Arthur, in case anyone wants to get me an especially lovely birthday present). And so I nearly had an aneurysm when I saw the solicitation from Yale University Press for a new facsimile: The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp.

Now, I couldn’t buy the deluxe edition. But I’ll be damned if I’d let a book I’d been fantasizing about for the last decade go totally un-bought. I picked it up yesterday from the Bob Miller Book Room.

My new baby!

But here’s the best bit:

Being, as I was, at headed for the Bob Miller Book Room, I thought I’d take the family to the Royal Ontario Museum for Maggie’s Daily Dose of Dinosaur and, lo and behold! They are currently showing a special exhibit on the Shahnameh! Among the ROM’s holdings are pages from another great Shahnama manuscript also broken up during the 20th century, the Great Mongol Shahnama. These and other pages on display from McGill University and other sources represent a rather depressing history of decontextualizing Islamic art, but that’s a post for another day. As an introduction to the stories and cultural value of the Shahnameh, the exhibition is absolutely worth seeing. They even have a copy of the 1981 Houghton Shahnameh from Harvard on display – “The most luxurious and lavishly illustrated royal manuscript” preserved to “document and contextualize…” the illustrations.

A context we only get now in facsimile, thanks Houghton.

The ROM’s Shahnama – The Persian “Book of Kings” exhibit runs until September 3, 2012 in the Wirth Gallery of the Middle East, Level 3.