November 21, 2017

A Short Note About Book Distribution

Good news first! The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2017 ed. Rich Horton (Prime Books 2017) is out, and I am in it! My contribution is “A Fine Balance,” originally published in the Nov/Dec 2016 issue of F&SF. I’m over the moon at being included!

Good news first! The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2017 ed. Rich Horton (Prime Books 2017) is out, and I am in it! My contribution is “A Fine Balance,” originally published in the Nov/Dec 2016 issue of F&SF. I’m over the moon at being included!

I… only wish it had been easier to actually get the book.

I work in a bookstore. I can, and do, order anything I like for myself, even under terms and conditions that we might not daily agree to. But this has been the second time this year that a book I appear in has been difficult, if not impossible, for me to bring in.

Last month, I spoke with a number of other writer/booksellers at a panel at Can*Con in Ottawa about how writers can interact with bookstores. Ultimately, it turned into an hour-long lesson on the supply chain, because writers don’t fully understand that getting published does not necessarily mean showing up in stores. Over the month since the con, I have come to realize even publishers do not understand how bookstores order and why they can’t get into stores.

So, I offer this to you: a quick breakdown, highlighting especially how the chain has changed in recent years to cut out smaller booksellers. I’ll borrow a thing or two mentioned by my fellow booksellers, Leah Bobet, Aura Beth Roy, and ‘Nathan Burgoine.

You write a manuscript.

![]()

A publisher (this might be you) turns it into a book.

![]()

The publisher places the book with a distributor.

![]()

The distributor sells the book to stores.

In addition, the distributor takes returns from bookstores, then can sell those books to other stores. The distributor also (often) will warehouse the book for a certain amount of time.

Bookstores like to deal with distributors, not publishers. This is because of the returns clause: most bookstores have the right to return usually 10-15% of their purchases to the distributor. The distributor gives the bookstore a credit when the books are received, and that credit can be spent on other books from that distributor. This means you might return a book from one publisher and spend the credit on a book from another publisher.

This is a credit worth having. It’s flexible. Dealing with each publisher individually would not only be a logistical nightmare, but it means your return credits would be of very limited use. What if that publisher only has one or two books? Nope. Consolidating through a distributor encourages bookstores to take risks on books and buy things from micropresses, because they aren’t trapped in a relationship with that one book.

From the publisher perspective, having a distributor allows them to mitigate the loss from returns, because those books stay in the distributor’s system longer, and can be re-sold to other stores. It allows them to get into bookstores all over the country/world, using that distributor’s infrastructure. It saves enormously on administrative nonsense. It opens the door into thousands of bookstores.

I understand publishers take a hit from this chain in two ways: one, the distributor takes a cut. They just do. That’s their price. Two, the distributor almost always allows returns from bookstores and thus, books will be returned, ultimately, to the publisher.

Nobody likes returns, but they are a fact of life in almost all retail. Every year, millions of new books are published. The bookstore buys them for roughly 40% off of cover price – meaning for every 2 new books we want to buy, we need to have sold 3 other books at full price. For every 2 books you see on the shelf, 3 other books had to be sold to pay for them. To say nothing of rent, labour, and operating costs. That’s a HUGE volume, and it never happens. If we had to wait to sell three book in order to buy two more, we would literally never buy new books. We’d just be sitting around waiting to move old, outdated stock.

Returns help. You send back last year’s fashions to make room for this year’s. Thus, the world goes around.

Some distributors have found a way to attract the business of nervous small publishers by offering that holy grail: NO RETURNS. Diamond Distribution, who specialize mainly in comic books, are the biggest of these. This is who distributes for Prime Books – the publishers of my Year’s Best.

How do they do this? Well, they put the burden on the bookseller. In order to be allowed to order from Diamond, the bookseller needs to buy a minimum number of their books – which, again, are mostly comics and small presses. This minimum order gives you the right to a very limited discount (less than 40%) and no returns. If you want to be able to return books, your minimum order needs to be even higher. Returns only apply to new books – not backlist – and they need to be sent back quickly. They don’t have any shelf life.

How do they do this? Well, they put the burden on the bookseller. In order to be allowed to order from Diamond, the bookseller needs to buy a minimum number of their books – which, again, are mostly comics and small presses. This minimum order gives you the right to a very limited discount (less than 40%) and no returns. If you want to be able to return books, your minimum order needs to be even higher. Returns only apply to new books – not backlist – and they need to be sent back quickly. They don’t have any shelf life.

This is a model built for comic distribution, where new issues come and go monthly. For books – and graphic novels – it is totally non-functional. For this reason, most big comic book publishers have left Diamond and gone to more conventional distributors.

These days, I only find myself face to face with Diamond if I am dealing with a small press. These guys are usually just inexperienced. They were burned once by a high return, and they are determined it will never happen again, so they go with the big name that won’t give their books back.

But their books will never reach bookstores. Very, very few independents can afford to open an account with Diamond, much less a big enough account to get the terms they need. Diamond is a graveyard for small presses.

This brings us to Ingram. Ingram is the Amazon of distributors: a huge, sprawling mess of every book ever, with no customer service and very rigid terms. Almost everyone lists with Ingram because they might as well. Ingram will allow you to list your books as non-returnable, if you need to. They means, of course, they won’t warehouse them, and they may not offer the bookstores a discount. The bookstore can technically get the book, but they aren’t encouraged to. Aside from lack of returns and bad discounts, Ingram doesn’t offer any useful cataloguing service, they have no customer service, and their shipping fees suck.

I did, after all, order my Year’s Bests from Ingram. They were printed on demand and are, thus, miscut. There was no discount, and they were shipped to Canada at a great cost to us. Even at my “wholesale” cost, they cost me 50% more than cover price.

I was going to put them on the shelf and sell them, but I can’t. Not looking like that. Not at those rates.

So, what does a writer or publisher do, if they want their books easily available in bookstores?

Writers, ask prospective publishers who they distribute their books through. If the answer is “direct,” run. You might as well print your own book.

If they only distribute through Diamond or Ingram, know that this means your books will not show up in indies. They may not even show up at your local B&N or Chapters.

There are lots of good, reputable distributors in both Canada and the US. There are the big guys, of course: the distribution arms of Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group. I give Perseus distribution a tentative thumbs up, though they have recently been bought up by Ingram and have become very difficult to deal with, even though they operate separately from Ingram.

There are also excellent small press distributors who understand very well the challenges small presses face. Independent Press Group (IPG) and National Book Network do great work. In Canada, we have Literary Press Group (LPG), LitDistCo, Raincoast Books, Brunswick Books, and UTP Book Distribution. There are more, many distributing in particular types of books (university presses, scholarly publishing, children’s books, etc.) Do some research. Ask your local bookseller what they think of your choices.

Publishers, one last thing about returns.

Returns suck. I get it. Especially if the book store chain you are working with doesn’t even give the books back – some will just pulp the books and then bill you for them. But there are ways you can work this into your contracts or publishing model.

DON’T REPRINT RIGHT AWAY. Initial sales are ALWAYS inflated. Wait until the three month mark, when returns start coming back. Obviously, use your professional judgement: if your book was Tweeted out by Obama or up for a major award, REPRINT FOR SURE. But if Indigo just happens to be using it as a doorstop in all its stores, maybe wait. Give it a minute.

ASK FOR YOUR BOOKS BACK. Pulping is not in any way the industry standard. Your distributor can ensure that your books come back to you in salable condition. Take these on book tours with you.

OFFER FLEXIBLE DISCOUNTS. This is especially applicable if your distributor works with a discounter for overstock books. Got lots leftover? High returns? Offer them out for a bigger discount. Sell ’em to a discounter in bulk. The book chain is many-faceted, and your business plan has to account for the different stages of a book’s life. You might lose money at some of these discounts, but that is made up for with the better sales you get on front list by being out there with books easily available.

*

Now, it’s possible that this is indicative of a seismic shift in the industry. Diamond and Ingram are perfectly sufficient for dealing with Amazon. If most of your sales are through Amazon, then maybe it’s worth cutting out booksellers in order to get risk-free distribution.

I think this is narrow thinking. Booksellers are your army. They are your boots on the ground. Even if readers increasingly buy their books online, they still visit bookstores to browse, to talk to the staff. They want to see what’s out there, connect with people who love what they do. A bookseller is worth a ZILLION Amazon algorithms. Worth at least ten book bloggers, in my humble opinion, because we are steeped in this stuff. You want us to champion your books. You want us to put it in the hands of your readers.

Open floor, here. Any questions? I’m happy to field any technical book chain or publishing questions here. Pick my brain. That’s what booksellers are for. If you appreciate this post (and others like it,) click below to tip!

February 8, 2016

Apologies to Clockwork Canada

I’m here to fess up. I have been a tremendously terrible person.

Last month, I went to a launch of Exile Editions’ latest anthology, Playground of Lost Toys (ed. Colleen Anderson & Ursula Pflug.) I didn’t really want to go. Lost Toys? I imagined an anthology of creepy dolly stories. And who were those editors, anyway? I went to the launch because I had friends in the anthology – sorry guys – that’s it.

I should have known better.

I’ve been familiar with Exile as a Canadian publisher for years, but up until a few years ago, I’d thought of them as a literary small press. They published Morley Callaghan and George Elliott Clarke; Leon Rooke and Daniel David Moses. Good ‘ol Canadian Literature. Not, frankly, my hat, but stuff we dutifully stocked at the store.

Then, out of nowhere, they published Dead North, an anthology of Canadian zombie stories. I thought this was super-weird, coming from Exile, but the cover art was so good that I overcame my boredom with zombies and bought it. I was pleasantly surprised: Dead North was a solid mix of literary and speculative fiction, zombie stories that did more work than just being gory thrill-rides. Then came Fractured, stories of the Canadian post-apocalypse. Another subject I thought had been done to death, but Dead North was good enough that I opted to give the creative team a chance. Fractured was another very solid book, managing to present original, literary work despite the well-trod path it started on.

Then came Playground, and, like I said, I thought the subject was silly. Despite loving the previous two anthologies, I let my prejudice rule my head. Toys are dumb! It’s probably all going to be horror, anyway. The publisher obviously doesn’t know anything about speculative fiction! Rawr, I am a jerk!

Well, the launch was amazing, for starters. Six readers, great stories, and one impromptu Bowie serenade. The food was good, there was beer, and my friends were there. I bought the book to be generous, but I read through it in two days. Fully half the stories made me laugh out loud, and I am a tough customer. The book was great. It looked so stupid (again, sorry) but it was great.

I learned my lesson, right? Ha ha! Ha! Ha.

I learned my lesson, right? Ha ha! Ha! Ha.

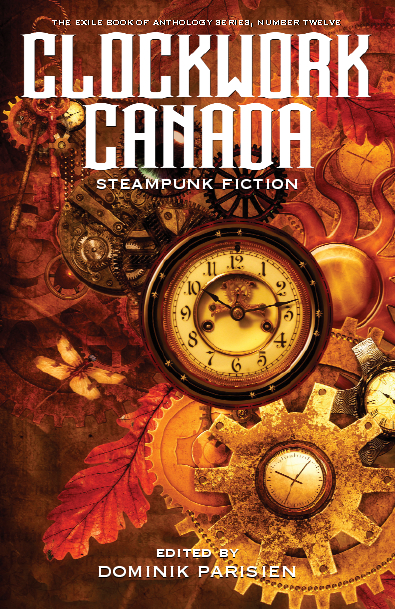

About a year ago, Exile put out a call for their next anthology: Clockwork Canada. Yep, Steampunk. And – you’d think I would know better by now – I rolled my eyes. Like, Steampunk, guys. Doesn’t Exile know this has been done to death? I know, I am the worst. Not a generous bone in my body. Only after I spoke with the editor, Dominik Parisien, did I even consider submitting, because he assured me they were looking for “Canadian alternative history of all kinds,” not just your usual airship stories. Yah, after four amazing anthologies, I still needed a tête-à-tête with the editor to convince me to even think about it.

Oh my God, am I ever glad I did. Dominik bought my offering, “La Clochemar” (no doubt because he had no idea what an asshole I had been about the whole Exile project,) and Exile managed to get us this ridiculously beautiful cover (right.) I am alongside some absolutely brilliant writers inside – writers who were probably far less diva about the whole thing than I was. All in all, the book seems set up to be another brilliant addition to what has been a brilliant series of speculative/lit short story anthologies. I… well, I am very excited.

Exile, Dominik – I am so, so sorry. You’ve never let me down! And look, people – here’s my pitch: we won’t let you down either. This is gonna be great.

You can pre-order Clockwork Canada now! It’s slated for release in early May 2016. Available from:

You can also drop us a note at our Goodreads page.

(Sorry!)

May 28, 2014

In Which I Invent Numbers

Last night I read Hugh Howey’s take on the whole Amazon vs Hachette thing. I don’t know why. I knew it would make me mad, and it did. Howey is, by all accounts, a super nice guy who is always available for emerging writers to pick his brain. He supports the community and tries his damnedest to make sure creators are not getting screwed. So I had to think that, rather than trying to shill for The Man, he must just be incredibly stupid and ignorant. I was up half the night seething bitterly about how many customers I would face tomorrow who felt entitled to have temper tantrums at the cash register because we/publishers are unfairly getting rich off their backs, and why can’t we all just discount books like that great Saviour of the People, Amazon???

Except Howey isn’t stupid and he knows how publishing works. So what was up with his backward-ass approach to explaining how publishers arrive at their prices?

Then it hit me. Howey is thinking like a self publisher. He thinks Hachette is a self publisher.

When you self publish, the money you spend up front to produce the book is a gamble. It’s the cost of having a dream fulfilled, or of getting your foot in the door. It’s a “long term investment”, betting on the day, five books down the road, when you really start to take off. Nine times out of ten, you never see that money again.

A publisher does not gamble any more than it has to. It looks at its costs – editors, designers, publicists, customer service reps, distributors, warehouses, printers, lawyers, mistakes, everything – and works out exactly how many books they need to sell at what cost in order to make it back. Some years a book hits big, and in those years, somebody makes bank. But most of the time, they pay their employees and produce books.

Howey’s assertion that Hachette “get[s] the full wholesale price of $8.99,” only makes sense if you think Hachette is a guy, like Howey. When a self-publisher sells a book, they use that money to pay back the loan they made to themselves during that book’s production – a cost that Howey seems to be counting after profits, the same way one might buy groceries or pay the hydro bill. Publishers do this the other way around. The wholesale cost of the book pays for the cost to produce the book. You only look at profits after everyone has been paid.

If a self-publisher never makes their money back, they may decline to self-publish again. If they were publishers, this would be called “going out of business”. Hachette isn’t super-keen to do this.

![]()

But let’s back up a bit. Let’s talk about Hachette’s “crazy” ebook prices, now that we understand that they are not gambling the same way a self-publisher might.

What does it cost to make a book? What % is the author really getting?

Here’s a simplified break down of the cost to self publish. Back-of-the-napkin stuff.

Book cover – $150 – $200 (this is cheap. CHEAP. You can do it for less, and we will be able to tell.)

Editing services – $400 (this is also cheap, but this is what I will charge you for an 80,000 word novel)

ISBN/expanded distribution – $99 (this is to get an ISBN you can use outside of Amazon)

Copyright registration – $85 (your work is automatically copyrighted, but many people choose to register for ease of legal protection. Many.)

Layout & Design – $150

Kirkus Review (this is a handy stand in for “publicity costs”)- $425

A website – $600

TOTAL – ~ $1900

This was done on the cheap. You could do it even cheaper, true, but you will pay instead with your time, sanity, and quality of product. So, your mileage may vary, but this is a handy number.

The million dollar question is, how many copies will you sell? Truly, nobody knows. Here are some things I do know:

90% of books registered with BookNet Canada only sell one copy. One. Copy.

Tobias Buckell dissected some Smashwords data last year that shows the vast, vast majority of titles sell fewer than 100 copies.

The best-selling anthology I have ever contributed to has sold 141 copies.

Award-winning YA author Arthur Slade reports selling an average of 635 books per title over a whole year, but this is 4780 copies of one best-seller and an average of 175 books for each other title.

But, that said, I know a lot of first-time self published authors of romance & teen books that come off Wattpad with “fan bases” of 5k+ followers. They expect to sell 500 copies in the first few months, and they do that or better. So if you have an established author presence and a book with a known audience, 500 is a good number to shoot for.

Let’s say you’ll sell 500 copies because I am being very generous.

You price your ebook at $5.99 because that’s what Hugh Howey did. You sold 500 copies. That’s nearly $3000.

Amazon takes 30% ($900)

The IRS takes 30% ($630)

You made $1470. Congrats!

Wait, sorry. I mean you are still short $430.

![]()

What about Hachette? How does this break down for them? Let’s look at one subsidiary, Orbit books.

I don’t know how many employees Orbit has, but let’s say you only need the ones that cover the same services the self-publisher paid out for themselves – even though they also need laywers, customer service reps, account managers and so on. Orbit publishes roughly 60 books a year, so we will assume a book gets 1/60th of their services (though in reality, things aren’t this fair – still, short hand). Salaries extrapolated from the bottom end of Indeed.com’s salary estimator.

Cover designer – $48,000/60 = $800

Editor – $47,000/60 = $784

ISBN = $5.75 (you can buy them in blocks for much less than they sell individually)

Copyright registration – $85

Layout & Design/Typography – $58,000/60 = $967

Publicity – $44,000/60 = $734

Printing – $3.90/book x 500 copies = $1950

Author Advance – $5000

Website – $0 (the publisher probably won’t do this for you!)

TOTAL – $10,325

Well, we printed 500 print copies. Let’s say we will sell these in addition to 500 ebooks, because I’m going to pretend I don’t know full well that plenty of big-5 titles only sell 150 copies, period. Let’s say Orbit has high hopes for you, and you will sell 1000 books.

If Orbit sold them for Howey’s $5.99, they’d have $5,990. Amazon would take 30% = $1790. I can’t guess at Orbit’s tax rate, but let’s be generous and say it’s 30% too. $1260. The distributor, by the way, wants 10% on the 500 print books you sold through them. That’s $300. Well, so far Orbit has lost almost $7000 on this book.

If MSRP was $8.99? $8990, and Amazon’s already paid. Well, we’re closer. They’ve only lost $4000. Incidentally, if they don’t pay the author an advance and just give them “25%” as Howey suggests, the author “only” gets $2250, but Orbit has only lost maybe $400. Another few months and they might break even.

Hachette’s barely eking by at $8.99 MSRP, and the author is $2250 ahead instead of $430 behind.

![]()

Everybody thinks they will do better. You can make this look better for Amazon & the author by selling more units. In scenario one, you will break even after you’ve sold another roughly 150 books. You’ll make the same as you might have in the Hachette scenario 760 books after that – so in order to make the same money on 1000 traditionally published books at $8.99 MSRP ($14.99 on Amazon), you’ll have to sell 1400 self published ones at $5.99. Maybe you think you will make those sales. I feel that this is… optimistic of you, but that’s your business. It is your dream to gamble on. You might, after all, make it big, like Hugh Howey.

But it would be business insanity for a mainstream publisher to operate as if they are guaranteed 1400, or even 500, sales of every book they publish. They know very well they have to balance the misses with the hits. They have been doing this for decades, after all.

And, of course, there’s the pesky issue of the salaries listed there. It costs more for a publisher to make a book because it employs people – real humans making middle-class salaries. We should not begrudge those people their jobs. Hell, most of them are probably the same creators Howey defends. The $2200 you might make self-publishing a book is not going to pay your bills, not unless you can write a novel every three weeks. Even being a freelance designer or editor isn’t going to pay your bills – not unless you are extraordinarily successful – or you put your prices up. I don’t edit six 80,000-novels per month, let me tell you.

No, it’s publishing that supports the entire creative industry. That’s where book lovers find jobs. Is that worth a buck per book to you? Is it to me.

May 2, 2014

Do We Have Diverse Books?

The hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks has been blowing up on Twitter this week. The idea is to give visibility (literally, photographs) to how little racial, gender, identity and ability diversity exists in publishing on all levels. We need diverse books, but we also need diverse stories, editors, publishers, agents and booksellers (eloquently elaborated upon by Daniel José Older on Buzzfeed and Bogi Takács both on eir blog and in Strange Horizons). No matter how you cut it, we need to see every face of humanity when we turn to a book.

Pictures are great, but is our money where our mouths are? I thought I’d take a trip around my own bookstore to have a look. I feel as if we offer a diverse selection of writers, but until you really take a calculator to it, you never really know. So here’s a case study based on our frontlist fiction shelf. These are the hardcovers on display at the very front of my store as of 10am on Friday, May 2nd 2014. This is what greets the buyer when they walk through the door.

Three Brothers by Peter Ackroyd (British Male)

Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine (Lebanese-American Male)

Forgiving the Angel by Jay Cantor (American Male)

The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton (Canadian-born New Zealand Female)

Every Day is for the Thief by Teju Cole (Nigerian-American Male)

Independence by Cecil Foster (Barbadian Canadian Male)

Andrew’s Brain by E.L. Doctorow (American Male)

Falling Out of Time by David Grossman (Israeli Male)

Boy in the Twilight by Yu Hua (Chinese Male)

The Wretched by Victor Hugo (French Male)

Fire in the Unnameable Country by Ghalib Islam (Bangladeshi Canadian Male)

In The Slender Margin by Eve Joseph (Canadian Female)

Kinder Than Solitude by Yiyun Li (Chinese American Female)

All Our Names by Dinaw Mengestu (Ethiopian-American Male)

Caught by Lisa Moore (Canadian Female)

Bark by Lorrie Moore (American Female)

Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor (Kenyan Female)

Between Friends by Amos Oz (Israeli Male)

Orfeo by Richard Powers (American Male)

Lovers at the Chameleon Club by Francine Prose (American Female)

Light and Dark by Natsume Soseki (Japanese Male)

The Valley of Amazement by Amy Tan (American Female)

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews (Canadian Female)

The Ever After of Ashwin Rao by Padma Viswanathan (Canadian Female)

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese (Ojibway Canadian Male)

By the Numbers:

In the interests of not spending all day picking into the personal lives of writers, I have decided to count only the most visible forms of diversity – race and presented gender. That will be what the readers sees when they pick up the book. Will they see people like themselves?

TOTAL # OF TITLES – 25

# Male – 15

# Female – 10

Country of Origin:

United States of America- 6

Canada – 6

Israel – 2

China – 2

Barbados – 1

Britain – 1

Lebanon – 1

Nigeria – 1

France – 1

Bangladesh – 1

Ethiopia – 1

Kenya – 1

Japan – 1

Visibly “white” – 13

Visibly a “Person of Colour” – 12

Biggest single group: White American Men, at 3.

*

Some notes:

I have opted to count writers by their country of birth rather than current residence because writers with solid literary reputations tend to be snapped up by big American universities. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is currently tenured at New York University and University of California, Irvine – I don’t think anyone would argue that he is not a Kenyan writer.

“Visibly white” is tricky business. I counted both Israeli men as “white”, though Grossman and Oz are both Middle Eastern Jews who write in Hebrew. They are clearly writing from a different place than Richard Powers or Victor Hugo.

Two-thirds of these displayed writers are men, but I should note our two biggest bestsellers of the quarter are Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch and Emma Donoghue’s Frog Music. These are not listed because they are sold out.

What does this mean for diversity? I think this looks good by a very low bar. We probably have one of the more diverse selections of books out there, but it is STILL a list in which more than half of the books are written by the dominant racial group. Putting aside countries of origin, a full 40% of them are American.

(Another 32% are Canadian, giving the North American contingent 72% of this shelf’s space – though this is mostly to do with the intricacies of publishing rights. We deal with Canadian distributors and Canadian publishers, who publish primarily domestic writers. International lists & translations do not make up the bulk of what they do. Another reason why “country of origin” is a more useful measure of diversity here: we want to see the faces of our neighbours, who are Canadian no matter how else they identify.)

Older asks us – those of us in the industry – to ask ourselves what we can do to make things better. What can we read, review, buy, sell? We carry fiction as a public service here – we don’t sell a tonne of it. We have it because we should, and when someone comes in looking, we want to be able to say yes. So we aren’t going to stop carrying Jay Cantor or E.L. Doctorow. These are good books. But we can add more good books. We take our cues from reviews, mentions in the newspaper, and customer requests. Last year one of our biggest fiction sellers was We Need New Names by Zimbabwean writer NoViolet Bulawayo because it got the buzz, and serious readers follow buzz.

To beat that dead horse, write reviews. Blog about what you’ve read. Pitch those reviews to the magazines and papers. Show the industry what’s good and nudge the buyers who’ll tell them what sells. Making a Top Ten Books That Do Something For Me list? Make sure it represents. If it doesn’t, wonder about what you’re reading. You are the mouth, my friends. We all are.

March 20, 2014

The state of my bookselling, 2014

I am still a bookseller. It is March 20th, 2014.

Everybody is surprised, me included. Every day customers wander through the door and look at me, startled, saying, “You’re still here!” My boss opens the till from time to time and demands to know who we have robbed, because cash appears to be accumulating. Our bills are paid. Our suppliers are satisfied. I have a normal, stable, middle-class job, and will hopefully soon be buying a house in downtown Toronto.

I am still a bookseller. Unlike, unfortunately, many of my colleagues. Toronto’s bookstore fatalities this year include the World’s Biggest Bookstore, the Annex branch of Book City, and the Cookbook Store (who will be having a farewell potluck this Sunday March 23rd starting at 11:30am). The culprits are Amazon and Toronto rents, the latter enemy being, likely, the bigger problem.

Courtesy of Biblioasis, who understand about having books on shelves.

Yet, I am still a bookseller. We are lucky to pay stable, and low, rent here. We carry unusual things and have a fiercely dedicated (and, frankly, solvent) customer base. We probably aren’t going anywhere, though some days I worry about the publishing industry’s ability to fill my store with books. As the midlist converts to e-formats and specialty books move to print-on-demand, it can be difficult to stock our bread-and-butter – the complete works of Immanuel Kant, for instance, or Will Kymlika. One of the few true benefits of a meat-space store is that we are right here, right now. If a customer comes in and asks for Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet, they mean now. Not, “Sure, we’ll take your order and that will be print-on-demand, non-returnable once it finally shows up in 3-4 weeks.”

This is the single weirdest shift I have noticed in the last 5 years. Books are getting harder for us to get. The same technology which is supposed to be making everything available to us all the time is gumming up the works. Books are getting much easier to get in one way: digitally, through Amazon. The process from writer to publisher (often the same person) to reader has become streamlined through the one fat Amazonian tube.

Optimizing your publishing process to slip down that river makes sense. You’re likely to make the bulk of your sales that way, especially if you are a smaller publisher without the means or the publicity to get your books onto bookshelves internationally. The time and effort required to then get your book into other distribution chains often isn’t worth it. A token effort – maybe checking the “extended distribution” box on Smashwords or Createspace, which in practice means making the book available as a POD title through Ingram – puts the book out there in a technical sense, but it will not be fast or cheap for the purchaser. And let me tell you, if it comes with the “non-returnable” caveat, we won’t buy it at all.

The only way we compete with Amazon is by having books on the shelves, not books in potentia in a database. On the flip side, the only way your reader is going to discover your books is by seeing that book. Maybe they’re seeing it mentioned on Twitter, or maybe they see it crop up on their friends’ Goodreads feeds – or maybe they see it on a bookshelf in a store. Amazon is a fantastically bad tool for book discoverability. George Packer did a wonderful job of breaking down Amazon’s arcane and for-profit search algorithms in his piece, Cheap Words. The long and the short of it is, readers can discover your book if you pay for it, or if you have some fantastic grassroots momentum going on. Otherwise, godspeed. You’re on your own.

Or, it might be worth the extra effort to make the book easily and readily available to actual bookstores, few though we may be. Booksellers are on your side – Amazon is not. We are book lovers, actual readers. We sell books not because we are looking to make a buck – though don’t get me wrong, my mortgage will be paid by that buck – but because we have made a genuine effort to understand your criteria, and we want you to enjoy the book we have suggested. We like what we do, and we are good at what we do. I guarantee that a single indy bookseller can hand-sell more copies of a book they loved than a reader can Tweeting that recommendation to their 250 followers. Both methods have their place, but if I had to hazard a guess, I’d say three-quarters or more of our customers come in without a specific book in mind. Like customers in a restaurant, all they know is they want something to read, and they’d like to see what we have, imagine the taste of each likely candidate, and to pick what they feel like at that moment. Maybe they have a craving for a specific read, but mostly, they don’t. They trust the bookseller, listen to what we know about the book’s content and accolades and they go away with something unexpected.

That’s what I do, because I am still a bookseller. For a little longer, anyway. So long as we can keep getting good, well-made books at a reasonable price in a timely manner. This is the 21st century – that should be easy, right?

December 12, 2012

Five Big-Idea Holiday Best-Sellers

My bookstore is an unusual one. We are a trade bookstore, but we have a disproportionate number of academics and intellectuals as customers and this has flavoured our stock. So when I look at other peoples’ round-ups of the biggest books of the season I often feel left out. We don’t sell a lot of fiction, so that pretty much leaves us out of the true bestselling loop, nor do we sell the usual celebrity memoirs, cookbooks, self-help scams or whatever else serves as the mainstay of most big bookstores.

We have our own bestsellers here, books I rarely see on other lists but which clearly resonate with a large percentage of the people who walk through the door. These are often big idea books: trade books still, intended for a general audience, but not quick reads for casual readers. If you have a heavy thinker on your holiday gift list, you could do worse than the following off-the-beaten-path works!

The Poetry of Thought: From Hellenism to Celan by George Steiner

The Poetry of Thought: From Hellenism to Celan by George Steiner

Steiner is a huge name in literary criticism and has been since the 60s, but my first encounter with him was through Eleanor Wachtel, whom he told in an interview that he felt there wasn’t much interesting going on in novels anymore (I’m paraphrasing). For a big reader of contemporary novels, this was a jarring thing to hear from someone who seemed to know so much. Steiner did admit he felt poetry was going places, however, and now he offers us a book giving full literary credibility to philosophy, to the act of philosophizing. The idea is remarkably new and Steiner has always been a pleasure to read. This is a must-have for the literary critic.

Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism by Judith Butler

Butler is a most un-classifiable academic, writing about gender, race, violence, politics, philosophy and anything else that seems to catch her fancy. At the end of the day, however, she is a literary critic, seeking to give us the tools we need to think critically about all those things we tend not to. Her latest, and by far the most popular new work of hers we have carried in a long time, tackles the Israel/Palestine problem. She mines the public sphere for support for her theories of cohabitation and ethic of social plurality, which is at the heart of her other work as well. You can’t write a word on the topic without being controversial, but Butler seems to be offering a good tool for critique without having to criticize.

Okay, a little Can-con. The Inconvenient Indian hasn’t been out as long as some of these others, so it hasn’t sold quite as well in terms of sheer numbers. But the way it is flying off the shelf now, I think is deserves a mention. King sells well here as an essayist, if not as a novelist. His Massey Lectures, The Truth About Stories is among the all-time top-selling Canadian books we have in the store, so it’s no surprise that the people who thought so highly of his last collection would come seeking the latest. The collection is funny, smart, insightful and a desperately-needed addition to Aboriginal Canadian history. King deserves to be better recognized as one of this country’s most important public intellectuals. On top of being a top-notch writer he is an engaged political figure, an academic and now a film-maker. When we speak of Margaret Atwood, we should speak of Thomas King in the same breath.

Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature by Charles Rosen

Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature by Charles Rosen

I picked this list three days ago, and so of course that’s the day Charles Rosen picks to die. I don’t mean to suggest I had anything to do with it, but honestly? Really? Freedom and the Arts is now officially Rosen’s “last and best” work, at least that’s what we’re calling it today. Rosen was one of those incredible people who just happens to be best at everything, and excels everywhere he chooses to allocate his effort. Rosen is best known as a pianist and a music writer, but this collection of essays covers everything from music to literature, philosophy and academia, and does it all with a beautiful word and a deft mind. I hate him for it, but this collection is just masterful.

Memorial : A Version of Homer’s Iliad by Alice Oswald

Memorial : A Version of Homer’s Iliad by Alice Oswald

There are some years when re-worked versions of Homer are a dime a dozen. I feel like Christopher Logue’s offerings weren’t that long ago (All Day Permanent Red was published in 2004) and David Malouf’s Ransom was actually published yesterday (i.e. 2010). And yet Oswald’s kick at the can is an incredible work. She seeks to memorialize in prose all two-hundred-plus people killed over the course of the Iliad, and manages to do so in a smart, sparse, 81-page poem.

November 12, 2012

University Press Week!

It’s University Press Week! This must be a new designation because in the past I have honoured university press books in a haphazard way, apparently at the wrong time of year. My efforts to get some Canadian university press books on the Canada Reads longlist was a sad failure, but those savvy folk at the Association of American University Presses have brought this one down in time for Christmas shopping. I have more than my share of opinions about what you should gift your loved ones with this year, so with no further ado, I give you three amazing university press offerings sitting on shelves right now!

It’s University Press Week! This must be a new designation because in the past I have honoured university press books in a haphazard way, apparently at the wrong time of year. My efforts to get some Canadian university press books on the Canada Reads longlist was a sad failure, but those savvy folk at the Association of American University Presses have brought this one down in time for Christmas shopping. I have more than my share of opinions about what you should gift your loved ones with this year, so with no further ado, I give you three amazing university press offerings sitting on shelves right now!

Harvard University Press’s Jane Austen Annotated Editions

Emma is the third in Harvard University Press’s Annotated Jane Austen series, and every bit as beautiful as the previous publications of Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion. The whole oeuvre of Austen in these hardcovers would be magnificent on the shelf of any collector, but be warned that no paperbacks are currently forthcoming. These are lavishly illustrated editions beautifully assembled, and would barely hold together in a less sturdy format. But at $35-$40 each, who could complain anyway? Harvard, by the way, seems to be going whole-hog into these amazing annotated editions. An annotated Frankenstein also appeared on our shelves this fall, and is no less recommended.

Northwestern University Press’s World Classics Series

I think one of the greatest services university presses renders is in keeping lesser-known works of great literature in print in good, well-edited and produced editions. Northwestern University Press has a number of these series, but I have a special spot in my heart for the World Classics. They have editions of the poetry of Pushkin and Pasternak, a lovely new Divine Comedy of Dante and Rilke. Lesser known additions include Anne Seymore Damer, Ivan Shcheglov, Luigi Meneghello and Ilya Ilf. These books are paperbacks, but exceed Penguin Classics and Oxford World’s Classics in quality by a mile. If you like NYRB editions, you’d love these.

Yale University Press’s The Woman Reader

Of course, most of what university presses tend to publish are academic books. This doesn’t, however, mean inaccessible, specialist books. Belinda Jack’s The Woman Reader is what Yale considers a “trade” publication, but this is a step beyond “books for anyone”. It is a historical overview of how women read, and have read, over the ages and cultures complete with endnotes and citations. But the book is anything but dry: Jack’s prose is succinct, funny, and totally readable by the non-specialist. Yale has a great backlist of similarly academic-but-enjoyable books on books, including Andrew Pettegree’s The Book in the Renaissance, Margaret Willes’s Reading Matters and Alberto Manguel’s A Reader on Reading.

October 23, 2012

Book-Lover’s Guilt

In case you weren’t feeling glum enough about the imminent closure of the Toronto Women’s Bookstore, last night we got the news that Canada’s largest independent publisher, Douglas & McIntyre, has filed for bankruptcy.

The news brought a chorus of astonished gasps and moans from Twitter. Nobody likes to see things like this. Good, experienced publishing people could lose their jobs. Writers could lose their publishers. Their books could go out of print. Oh, and something about the cultural contribution too. Canadian culture, supporting our own, something something.

Of course, if everyone who was so sad to see them in straits actually spent money on their books, they might not be so bad off. That was the first thing I thought, in any case. Oh man, when was the last time I bought a Douglas & McIntyre book, anyway? The summer of 2010, Darwin’s Bastards, Zsuzsi Gardner? July 2010. Cigar Box Banjo, Paul Quarrington, for my husband’s birthday. November 2011, Something Fierce, Carmen Aguirre, for Canada Reads. That’s $80 in two years. No wonder they’re going out of business! Why didn’t I pick up Daniel O’Thunder, Lightning, The Book of Marvels when I saw them? And why didn’t I buy them all at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore?!

The fact is I can barely feed myself and my children, let alone every writer, publisher and bookseller in Canada. But that doesn’t prevent the lingering guilty feeling that I somehow should have tried.

My coworkers and I sit here scratching our heads this morning, wondering how this could have happened to D&M. They have a phenomenal list. We bring in – and sell – almost every single book they publish. What more must a publisher provide? Great, well made books that people want to buy. Isn’t that the formula? How can that fail to pay the bills?

Admittedly, I live in a bubble. Our bookstore sells books nobody else can manage to move. My customers are heavy readers who – bless them – never ask about the prices, just pay them. My friends are heavily educated and literate, with a strong sense of social responsibility when it comes to supporting the local. My 276 Twitter followers seem to be 200 authors, 75 publicists and my mom. The millions of people who buy and read 50 Shades of Grey? I don’t know who they are.

So maybe out there in the real world, D&M’s excellent books are going unnoticed. Maybe all the “buzz” the journalists, bloggers, reviewers and publicists claim to be out there is being generated by review copies and good intentions. I’m a bookseller and a blogger, after all. I have my share of books given to me, and what I buy I often buy at cost. Maybe I am to blame after all. Do we excuse ourselves from buying books because we feel our endorsement, our “word of mouth” is worth more than the $19.95 we’d spend on the book? I wonder sometimes. I don’t know how else to reconcile the contradiction I’m seeing. We all love and “support” these books, and yet the money isn’t there. Are the readers – the ones who don’t work for the publishing houses, who don’t get their copies for free – there? Are they reading our reviews and buying the books? Does buzz equal sales?

We’re troubled, this morning, about what this could all mean. If a Douglas & McIntyre can’t make it, I wonder if anyone can. Does a publisher need to be propped up by a mega-bestseller (and does a Canada Reads winner not suffice)?

October 1, 2012

An Anniversary of Sorts

The shortlist for the 2012 Scotiabank Giller Prize was announced this morning, which in a bookstore means a rapid once-over of the store and the orders to see what we have and what we need get into stock. We managed 1/5 this year; not our worst year. In doing my research, I happened to notice that it has now been 10 years since I started working in the bookstore. The shortlist of 2002 was the first I ever worked on.

We’ve never been the kind of bookstore to attract bestseller-like traffic, but we do pride ourselves in keeping a long backlist. So while we didn’t sell many copies of that year’s winner – Austin Clarke’s The Polished Hoe – we do still have it in stock. Looking back to that 2002 shortlist, I’m pleased to see we actually still have 4/5 of THOSE books. Maybe this is a testament to the lasting value of those books, or maybe we’re just slow on the uptake. But if ever you’ve doubted the strength of the books that make a Giller shortlist, look back:

Austin Clarke, The Polished Hoe

Bill Gaston, Mount Appetite

Wayne Johnston, The Navigator of New York

Lisa Moore, Open

Carol Shields, Unless

Ten years on, those choices hold strong.

So I suppose what I’ve learned in ten years of bookselling is that however random and unworthy a list may or may not look at the time, only time can really bear it out. Those jurists are no fools, and what is today unknown to us might be classic tomorrow.

September 26, 2012

Back From Leave!

I do mix bookselling and parenting. A little.

I’ve been back at the store exactly one month now, launched from the relatively peaceful life of the stay-at-home mom into the bustling world of trade bookselling successfully. We’re at the height of our busy season now, receiving and selling thousands upon thousands of books for the 2012-13 university year. Even so, I have had more time to read, write and think in the last 30 days than I had in the previous 320.

I am pleased to find that very little has changed here. In fact, books still sit on the shelf exactly where I left them one year ago. The same customers come looking for the same books, the same professors ask us to provide the same books for the same English students. From the news I’d found on the Internet it had seemed as if the book business was changing entirely every week I was away, and I’d wondered if I’d even have a bookstore to come back to. Ebooks continue to find their place in the market, publishers fold and get sold, and Amazon continues to come up with new innovations to destroy us all reinvent bookselling. But no, now that I’d back in the belly of the beast, I see very little has changed after all.

Part of the stasis I’m seeing seems to come of the differing aims and ideas of bookselling’s players. Amazon introduces same day shipping, but ever more titles are shifting to print-on-demand. Ebooks continue to gain market share, but our students are discovering the format’s limitations. People are still buying books in bookstores, and demographically it seems likely to continue for some time. If ebooks or internet sales are ultimately going to put an end to my line of work, they aren’t doing so quickly, at least not until they get their acts together and form a unified plan of attack.

There are two big reasons people continue to come into the shop, and neither one of them is because of the patient and romantic respect for the time-honoured profession of bookselling. As much as individuals wax eloquent about the community services and individual attention neighbourhood bookstores provide, at the end of the day every one of you succumbs to the convenience and savings offered by Amazon or Chapters-Indigo.ca. Very few people really boycott big online sellers. To do so requires some sacrifice on the part of the book-buyer, and we’re not a people who are generally fond of sacrifice. To cite a recent example of the disconnect between professed love of independent booksellers and the reality of the indie’s powers I offer up Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, Joseph Anton. This memoir of Rushdie’s years spent under fatwa has been, in publicist lingo, “hotly anticipated” to the point where it was classified as an embargoed title, meaning there would be no advance reading copies and no shipments of the book in advance of the release date. Logistically this tends to mean that stores who order enough copies of the book to receive sealed boxes (containing perhaps 12 copies) will get their shipments on the release date, but if you have ordered fewer than a box worth, you have to wait until the cases have been cracked and individual copies can safely go out. In our case, because we ordered only five copies, this meant we received our books on September 24th rather than the 18th.

So while on the one hand, Rushdie crafted an open love-letter to independent booksellers for their support of Satanic Verses while he was under fatwa, in reality, most independent bookstores miss whatever mad scramble the publisher thought there would be for this book. Will the buyer wait? I had a few requests for the title on the 18th, but I have not yet sold any of the copies which came in on the 24th. I suspect, no she won’t.

Yet people do show up and we do sell books. The biggest draw is convenience. When we have the books, they are on the shelf right there. You don’t have to wait, or order. You pick it up and start reading that minute. For students this is especially relevant, because often it doesn’t occur to them to buy the book until they are three days from an essay’s deadline. They can’t wait. This is, of course, one of the biggest draws of the ebook as well – there you don’t even necessarily need to leave your home to instantly receive your book. Yet whatever market share we’ve lost to ebooks we’ve made up for by the loss of older competitors. Chapters Indigo don’t seem to carry many books anymore. One desperate student calling to confirm we had his book in stock informed us that the closest copy Chapters had of Lattimore’s translation of Homer’s The Odyssey – surely an easy-to-find staple if ever there was one – was in Stoney Creek. The ease of “finding a used copy” has also tanked, as used bookstores around the GTA go belly-up. A few monster used bookstores don’t make a suitable replacement either – while ten small stores might have an Odyssey each, that doesn’t mean one big one will have ten copies. We have books, so people come to buy them.

The second draw remains a fundamental mistrust of ebooks. Consumers may be warming to the idea, but in my experience, many ebook readers have mistaken ideas of what an ebook is, and what rights it gives them. Several people have tried to return ebooks to us because they discovered they “could not print them out”. For a student or academic, having a paper copy – even in fragments – is still key. You need somewhere to scribble your notes. You need a copy to bring in to the exam. You need to copy a chapter for your students. These consumers also have mistaken ideas about to what extent they own the “book” they’ve bought. They want to lend it out, to sell it when they are done. They need access to it even if they’re having technical difficulties. It is apparently easier to phone me than to reach tech support for many ebook publishers, and I find myself trouble-shooting my customers’ reading experience. This is in no way my job, and while I like to be helpful I am reluctant to be yelled at when a customer is, for whatever reason, locked out of her book. Loathe as I am to ever refuse to help a customer, I begin to wonder if I should even admit I know anything about ebook difficulties. To own up to any knowledge seem to be to invite blame. To avoid headaches, I recommend paper books every time.

So I don’t know if it will last, but as of today the bubble holds strong. People read, and we facilitate reading. The thrill of a new release, a new find, or a new favourite hasn’t gotten old for the customers or for the seller. I count myself lucky that I can still be in the business now, and I hope to still be here in 15 years. And beyond? I’m not willing to forecast, just enjoying the good weather while it lasts.