April 25, 2011

Things to do this weekend: Wayzgoose!

I couldn’t possibly be more excited about this weekend, because for the first time in years I will be traveling outside of Toronto exclusively for a bookish event: the 33rd Annual Wayzgoose in Grimsby, Ontario.

I couldn’t possibly be more excited about this weekend, because for the first time in years I will be traveling outside of Toronto exclusively for a bookish event: the 33rd Annual Wayzgoose in Grimsby, Ontario.

There are a lot of bookish events in Ontario, but this is the only one I can think of dedicated specifically to the “Book Arts” rather than, say, publishing, reading, or rare/used books. That’s probably why they now boast attendance of upwards 2000 people from all over the world – this isn’t exactly an opportunity to sell books or schmooze so much as it’s a genuine festival, a celebration of the arts that bring you printed books: letterpress printing, paper making, bookbinding, marbling, calligraphy and more. I look forward to demonstrations and displays as well as the opportunity to spend money on one-of-a-kind books from odd and out-of-the-way bookmakers.

I started this post, by the way, with the impression that the Wayzgoose was founded and hosted by Erin, Ontario’s Porcupine’s Quill Press, but after some research I discover this is not the case. The Wayzgoose is entirely independent, officially sponsored by the Grimsby Public Art Gallery. My confusion probably stems from the fact that Porcupine’s Quill is enormously supportive of the endeavor, especially as they publish Canada’s only dedicated Book Arts journal, the Devil’s Artisan. It is through Porcupine’s Quill that I learned of the event and because of their cheerleading that I am so psyched about the event – and probably also because of one or two excellent wares they promise to have available: a new issue of D.A. and a new facsimile edition of George Walker’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

And to wander further off on a tangent, Porcupine’s Quill seems to be making a stab at replacing Gaspereau Press as the country’s most talked-about craft press – not only are they running a social-media contest right now to promote Alice’s Adventures, but I spotted their little ad in the print edition of this weekend’s Globe and Mail books pages. I choose to interpret this as evidence of a surge of interest in the book arts. Who’s with me?

Well nevermind, but I will be in Grimsby on Saturday, and I hope some of you will be to!

April 20, 2011

Pigeon English & Voice

After a hiccup earlier this month, I finally went back and plowed through the last fifty pages of Steven Kelman’s promising debut novel, Pigeon English. It was difficult, but not because of the quality of the book – this will not be, per se, a review proper, but let me just assure you right off the bat that this is a good book, whatever else I will say about it below. No, it was difficult because it is a tragic book, and at the moment I am feeling particularly unable to deal with stories in which horrible things happen to children. This isn’t much of a spoiler, by the way. The first page opens with one child’s ruminations on the blood leaking out of another, dead, child.

After a hiccup earlier this month, I finally went back and plowed through the last fifty pages of Steven Kelman’s promising debut novel, Pigeon English. It was difficult, but not because of the quality of the book – this will not be, per se, a review proper, but let me just assure you right off the bat that this is a good book, whatever else I will say about it below. No, it was difficult because it is a tragic book, and at the moment I am feeling particularly unable to deal with stories in which horrible things happen to children. This isn’t much of a spoiler, by the way. The first page opens with one child’s ruminations on the blood leaking out of another, dead, child.

Kelman’s novel is set in a ghetto where 11-year-old Harrison Opoku has settled after immigrating to England from Ghana with his mother and older sister. Unlike in so many other books about poverty and social decline depicted in terms of the unreadably tragic horrors they wreak on children – Heather O’Neill’s Lullabies for Little Criminals comes immediately to mind – Opoku’s personal history isn’t terribly dark at all. He has a father, baby sister and grandmother back in Ghana who are just waiting for their turn to join the rest of the family in the UK. Kelman hasn’t burdened Harri with abusive caregivers, any history of sexual abuse, drug addiction, child labour, early loss – none of that. He’s just an observant and adventurous kid taking in his new society as it comes to him. He seems like he might come through whatever trials this impoverished English neighbourhood might offer him in good shape.

The story is told in the first person by Harri with only occasional (and ill-advised) digressions into the head of a pigeon. I found this choice of voice – Harri, not the pigeon – problematic. I don’t take issue in general with authors who choose to tell a story in a voice completely unlike their own. Authors who choose to give a voice to minorities, the mentally ill, murderers, animals, or cans o’ beans are welcome to do so regardless of their own age, colouring or species. In doing so they often give voices to segments of the population utterly under-represented in fiction. Kelman’s background growing up in an estate similar to Harri’s even gives him some insider credibility – he knows what it is to be a kid in a housing project. Very well.

Regardless, I found myself skeptical of the direction Harri’s story took, a doubt that would have been dispelled if I’d felt the author was a little more representative of the character he was giving voice to. I felt there was a disconnection between Harri’s relatively stable situation and innocent voice, and the fate that eventually befalls him. Why Harri, who has friends, family and a strong sense of self, should have become embroiled with the Dell Farm Crew isn’t entirely clear to me, unless we assume powerful gangs offer equal temptation to all young boys. Though doesn’t that to some extent dull the argument sometimes made that the young men in violent gangs are “troubled”; that gangs are the last refuge for a culture of poor, powerless boys without strong paternal guidance? Certainly the implication offered by HBO’s stunning (and utterly believable) series The Wire is that young people are sucked into the violence of the “corners” are forced there by deteriorating social conditions and horrifying personal circumstances. Harri, coming from a place of relative strength, doesn’t seem to belong there.

Kelman’s thesis can be said to be, then, that this can happen even to smart, resourceful young men who just happen to live in the wrong place and who turn up at the wrong time. The real tragedy of Harri’s story is that he’s fundamentally a good kid, and still gets eaten by the estate. I’m skeptical. Many people, every day, survive the ghettos, projects and housing estates of deteriorating Western cities. Why not Harri? Is this just a story of bad luck? I’d feel reassured if I knew the author really had been there. Given a claim that seems dubious to me, I’d appreciate a claimant with more authority. It would leave me with a better sense that Pigeon English is a book about the rot of Western society, rather than it’s being another addition to the growing ranks of tragedy-porn.

But enough of that. I maintain the book is basically good. It has other virtues, and I encourage you to read the review offered by Kerry Clare at Pickle Me This. Kelman has a clear talent for evoking and provoking, and I’d eagerly check out whatever he has to offer next.

April 18, 2011

Objects Found in Books

One of my favourite bookish news stories from the last month is this one in which a typed letter from Robertson Davies to New Canadian Library co-founder Malcolm Ross was found in the pages of a book bought at a Halifax Salvation Army shop for $1. This kind of thing actually happens all the time, though perhaps not so often with such bright lights of Canadian literary history. From as far back as books have been produced in codex-form, people have been putting flattish things in between the pages and have forgetting them there. One of the great pleasures of buying second-hand books is finding them again.

Sometimes this kind of ephemera can be quite valuable to collectors and to libraries, a hunger wonderfully novelized by A.S. Byatt in Possession. More often it is simply another layer of history passed down through the object to the new reader. Old bookmarks, receipts, notes and letters; even pressed flowers, locks of hair and ribbons give a used book a unique character that separates it from other copies of the same book. Even this can be of value to a book history scholar (again, beautifully novelized by Geraldine Brooks in her recent People of the Book), but personally I love the way it gives me my own mystery to solve; good for nothing, probably, but telling a story.

Two great-aunts of mine, both spinster librarians who kept up friendly correspondence with writerly contemporaries of theirs, were great clippers and hoarders. Few books I’ve inherited from them are free from newspaper clippings, letters and photocopied notes from other books. An old biography of Rudyard Kipling contains clipped Kipling poetry from a 1920s newspaper, while my facsimile of John Gerard’s 1633 Herbal has notes on the authors photocopied from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Two great-aunts of mine, both spinster librarians who kept up friendly correspondence with writerly contemporaries of theirs, were great clippers and hoarders. Few books I’ve inherited from them are free from newspaper clippings, letters and photocopied notes from other books. An old biography of Rudyard Kipling contains clipped Kipling poetry from a 1920s newspaper, while my facsimile of John Gerard’s 1633 Herbal has notes on the authors photocopied from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

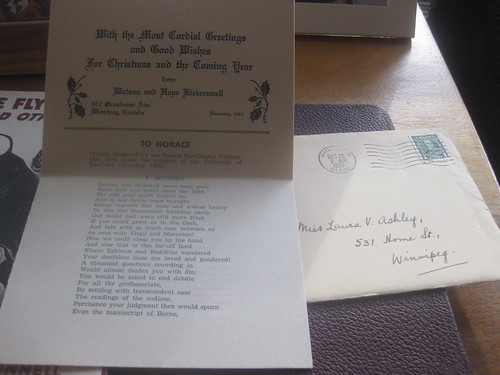

One aunt in particular seems to have been a friend of the Western Canadian author Watson Kirkconnel. One of my favourite ephemeral findings is a Christmas card, sent in 1935, from Kirkconnel and his wife featuring a poem, “To Horace”, otherwise unpublished. Though Kirkconnel is utterly unknown and out of print today, the addition of this cheerful little relic of the past makes this book (a limited edition copy of his Flying Bull and Other Stories) one of my favourites. Kirkconnel has posthumously become an imaginary family friend, part of my own past. Other letters and clippings from Kirkconnel adorn other books in my library: I like to invent and exaggerate the dimensions of my aunt’s relationship with the once-great author. The artifacts give me that right, I think.

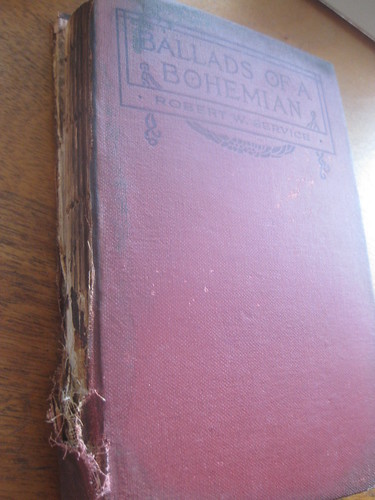

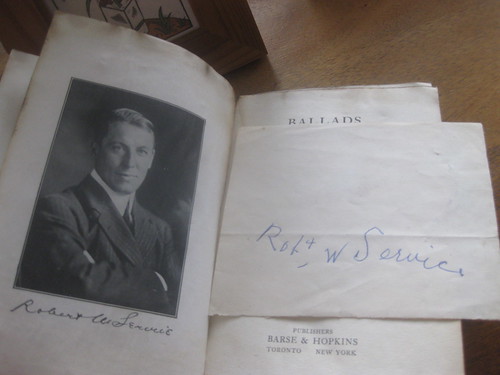

Once when I was very young I snuck into a broken-down house known to me in order to “liberate” a very musty and dilapidated old tome I saw there. I imagined that, being an old broken-down house, all printed materials found within must necessarily be mysterious, valuable, and possibly occult. I was both very wrong and very right. The book, Robert Service’s Ballads of a Bohemian, is utterly worthless because of the condition it is in – torn, moldy, and even slightly burnt-up. On the other hand, it appears to contain a slip of paper bearing Service’s signature. The book is not signed directly, but the name is written on a separate slip found facing the portrait of the author. Is it really the author’s signature? I have no idea. It is not a clean and tidy signature, and looks instead to have been made by someone very advanced in years, or in deteriorating health. That said, that nearly rules out its being a copy or forgery. Any attempt to mislead would surely be closer to the “official” thing. But why else would it be there? This is my bookish mystery. The myth associated with my finding and retrieving this book certainly sounds better if the tale ends with its being a signed copy. Well, it’s my unique relic so, again, I reserve the right to tell the story. It’s signed, my own treasure.

Once when I was very young I snuck into a broken-down house known to me in order to “liberate” a very musty and dilapidated old tome I saw there. I imagined that, being an old broken-down house, all printed materials found within must necessarily be mysterious, valuable, and possibly occult. I was both very wrong and very right. The book, Robert Service’s Ballads of a Bohemian, is utterly worthless because of the condition it is in – torn, moldy, and even slightly burnt-up. On the other hand, it appears to contain a slip of paper bearing Service’s signature. The book is not signed directly, but the name is written on a separate slip found facing the portrait of the author. Is it really the author’s signature? I have no idea. It is not a clean and tidy signature, and looks instead to have been made by someone very advanced in years, or in deteriorating health. That said, that nearly rules out its being a copy or forgery. Any attempt to mislead would surely be closer to the “official” thing. But why else would it be there? This is my bookish mystery. The myth associated with my finding and retrieving this book certainly sounds better if the tale ends with its being a signed copy. Well, it’s my unique relic so, again, I reserve the right to tell the story. It’s signed, my own treasure.

To beat that poor old horse, it would be a real shame if the digital future inadvertently limited or destroyed the preservation of ephemera. Casual insertion of things into day-to-day books has brought a wealth of everyday artifacts to us. It goes without saying that nothing can be inserted into an ebook, but moreover, it’s more rare for things to be inserted into valuable or collector books. A theoretical future where the remaining printed books are more highly valued as artifacts is one where people are less likely to stick any old thing between the pages. Casually read books are the ones which come to us with the heaviest signs of their history. I was struck while re-reading Frank Herbert’s Emperor of Dune by a scene in which a high-tech book is stolen and then, between the pages, a dried flower is found. The discovery is significant to the characters but also oddly anachronistic. Even in the year 13,000 we’re to presume that the book has remained as much a vehicle for material pieces of life as much as of information.

Of course the ephemera itself is disappearing more quickly than the book in any case. Newspapers? Letters? Recipe cards? Relics of past generations moreso than books. But I’ll miss, you know, receipts, bookmarks and flowers. Wouldn’t you?

April 15, 2011

The Sadness of Books We Can’t Sell

There’s a depressing side to returns season. It comes near the tail-end of the fiscal year, when we can delay the inevitable no longer and have to send back books which we’d been holding on to as long as possible for sentimental reasons; books which “should” sell. What’s maybe more depressing is that books that don’t sell usually fall into very specific categories, and so maybe as booksellers we should learn simply not to order from these lists. After all, our job isn’t to snobbishly insist readers should be reading one thing or another, it’s to provide them with a good choice of things they might be interested in. So why, after years of failing to sell some of these books, do we keep ordering them? Optimism, I suppose.

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

This is an especially sad category considering the wealth of absolutely amazing Canadian YA lit being published. I have no doubt that companies like Groundwood Books do stunningly well through the school and library markets, but we sell precious none of them off the shelves. Children’s books – picture books – do very well, probably because it’s parents who buy them. YA fiction featuring vampires, wizards, witches, time travelers and talking animals also do just fine. Classic children’s novels like The Secret Garden, Five Children and It, Swallows and Amazons and so on also do fine (though, again, often purchased by grand/parents).

But good, insightful plain fiction aimed at young adults? Forget it. Not that that stops us from filling the shelves with Glen Huser, Polly Horvath, Alan Cumyn, Tim Wynn-Jones and Paul Yee. We just have to send them all away again at the end of every year.

Chinese Literature

Chinese Literature

Literature in translation goes through fads and phases until a region has accumulated a critical mass of Nobel Prizes or Booker Internationals. These days Middle Eastern literature is starting to come into vogue. And, you know, great! Fabulous books like Al-Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building and Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun are getting well-deserved love, and Tablet & Pen: Literary Landscapes from the Modern Middle East ed. Reza Aslan has been a surprise best-seller for us.

But oh man, China. Its day in the literary limelight has not yet arrived. Gao Xingjian won the Nobel prize in 2000, the first Chinese writer to do so, but I defy you to name offhand a single book of his (I had to look it up on Wikipedia, and even then nothing looked familiar). We do bring the translated books in – A Cheng’s King of Trees, Bi Feiyu’s, Three Sisters, Jiang Rong’s, Wolf Totem and much more – but they don’t go back out again. Tuttle Publishing is even doing wonderful new editions of “Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese Literature” – The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey Into the West – which we have valiantly kept on the dusty shelves these past ten years, to no avail.

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

You’ll be surprised to know that Russian literature didn’t die with Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn! Despite forays into internationally renown territory like Victor Pelevin’s contribution of Helmet of Horror to the Canongate Myth series (which also brought us, among other things, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad), I think I’d be safe in saying that post-soviet Russian novels are being completely ignored by Western media, critics and readers.

But there’s plenty to be had. NYRB has published some of the best offerings (though, see below), including Tatyana Tolstaya’s The Slynx and Vladimir Sorokin’s The Ice Trilogy (which I cannot wait to read, for reals). Plenty of Pelevin’s books have been translated and published by big, international publishers. But buyers? Well, not here.

NYRB Classics

NYRB Classics

We don’t sell none of these, so maybe this isn’t a great example. But we do tend to order absolutely everything they publish because their books are so damn good, so when it comes time to return and we’re sending back most of them, it looks particularly bad.

NYRB publishes some truly under-represented bodies of work, like literature in translation outside of your usual Nobel laureates and international bestsellers and literature from the 20s and 30s not written by Faulkner, Hemingway or Fitzgerald. Perhaps, then, this is why they tend to be slow in the selling. It’s hard to sell Elizabeth von Arnim as “frontlist” or “new” when she died in 1941 (and doesn’t have the cheerleading squad that Irène Némirovsky has), even if The Enchanted April is in a beautiful new edition and a wonderful book. People haven’t heard of her, and they’re more likely to pick up the new Cynthia Ozick or Eva Hoffman.

Always exceptions, of course. As I mentioned, Arabic lit is all the rage around these parts nowadays, and NYRB brought us Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih, which sells like those proverbial hotcakes.

Oh well. I suppose if it weren’t these books, it would be something else going back! There are so many books and so little time. Maybe when I finish sending all these lovelies away, I can get to work reading some of the survivors!

April 8, 2011

I can YOSS too!

A bunch of smart and dedicated persons (I hesitate to say “ladies”, but I think they might all be ladies) have declared 2011 to be the Year of the Short Story. Now while I don’t think I am very likely to want to spend a year reading nothing but short stories (which is not, by the way, what they are suggesting), I can’t argue with their aim: to bring short fiction to a larger audience.

A bunch of smart and dedicated persons (I hesitate to say “ladies”, but I think they might all be ladies) have declared 2011 to be the Year of the Short Story. Now while I don’t think I am very likely to want to spend a year reading nothing but short stories (which is not, by the way, what they are suggesting), I can’t argue with their aim: to bring short fiction to a larger audience.

Once upon a time I was a heavy short story reader. I am now a light short story reader. The last anthology I read was I read was Neil Gaiman & Al Sarrantonio’s Stories, which I’d say was a mixed success. It certainly contained a couple stories I just loved (notably Neil Gaiman’s The Truth Is A Cave In The Black Mountains and Michael Moorcock’s Stories), and at least one I want to go back to (Jeffrey Ford’s Polka Dots and Moonbeams). But it also had it’s share of silly, hackneyed stories featuring overdone themes – like Walter Mosley’s Juvenal Nyx (oh good, another angsty, vampire-with-a-soul story) and Joanne Harris’s Wildfire in Manhattan (gods of old WALK AMONG US).

But this is the nice thing about short stories. Even within one collection, you can taste such a variety of persons, places and ideas. They’re easy to dip into and out of, and to go back to. Any collection is bound to have at least one story you’d recommend to a friend, whereas I’m not sure I’d ever recommend a chapter of a book to anyone. They offer a level of accessibility without triviality.

I’ll put my money where my mouth is – per YOSS suggestion #1, I am buying more short stories. And last night, this came in the mail!

Check it out – my Limited Edition (59/300) copy of Machine of Death: A Collection of Stories About People Who Know How They Will Die ed. Ryan North, Matthew Bennardo & David Malki ! I’ll be honest, I don’t know any of the authors, but each story is illustrated by a cartoonist, many of whom I am a big fan of. But no, I didn’t buy it for the pictures. That might have been an excuse (that and the Certificate of Predicted Death), but it’s also a chance for me to sample stories by a variety of writers who I might otherwise never encounter, as recommended to me by cartoonists I trust. And, you know, then there’s the pictures. And the chance to have them all signed next month at TCAF.

The short story world is full of fun gems like this! I hope you’ll seek one or two out this year too. Sometimes the most interesting reads are off the beaten track [of novels]!

April 6, 2011

Upcoming Book Geekery

It’s a quiet time of year here for us at the bookstore, but that means a lot of quiet, intimate time with the publisher catalogues. A dangerous time of year, as you can imagine. I am additionally imperiled by the fact that I will be on maternity leave by mid-July this year, and so I’m feeling a need to pre-order all kinds of things before I’m “out of the loop” for a year, as it were.

What kinds of things? Well.

Titus Awakes by Mervyn Peake & Maeve Gilmore

Titus Awakes by Mervyn Peake & Maeve Gilmore

I’m skeptical about works published post-humously, generally. Especially things possibly never intended for publication based on “manuscripts” or worse still “fragments” found years later by family members.

The circumstances surrounding this books “discovery” are also a bit suspect. Peake’s widow, Maeve Gilmore, wrote or finished a manuscript based on Peake’s notes in the 1970s, but the manuscript was “lost”. In 2010 the manuscript was “found” in a family attic – just in time for Peake’s centenary! Convenient, no?

Even still, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy (now, apparently, a tetrology) is one of my most beloved works of literature, and I can’t resist more.

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

How can anyone not be excited about a new Murakami novel? Goodness knows the Japanese lost their minds over it, apparently buying up almost 450,000 copies of the first volume (it was published in three parts in Japanese) before it was even published.

I adored Kafka on the Shore and Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. I tend to use the term “postmodern” disdainfully, but I’m a complete hypocrite – in reality many of my favourite modern novels are way out on the wacky fringe of postmodern surrealism – Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Murakami, Rushdie, Marquez. That 1Q84 is being described as Murakami’s “magnum opus”, and “a mandatory read for anyone trying to get to grips with contemporary Japanese culture” just adds to the appeal. 1000 pages plus of a “complex and surreal” narrative? Sign me up!

Il Cimitero di Praga by Umberto Eco

Il Cimitero di Praga by Umberto Eco

Okay, this one’s a bit cheaty because what I’m really looking forward to is the eventual (and inevitable) English translation, The Cemetery of Prague, which hasn’t been published yet.

The story of the genesis and history of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion is a great one for book history lovers. In Umberto Eco’s hands, it’s a tale of intrigue and conspiracy. The book has come under some criticism for blurring some lines between genuine antisemitism and fictional antisemitism, but I don’t personally believe for one second that Eco is genuinely antisemitic. He has said: “I’m interested in recounting how through the accumulation of these stereotypes the ‘Protocols’ were constructed. [..] My intention was to give the reader a punch in the stomach.” and I believe him.

That the plot of Alexandre Dumas’s Joseph Balsamo also plays a large part in the plot of this novel is also a HUGE draw. Surprise!

How imminent is an English translation? No idea! But I refuse to miss it just because I’m sitting at home with my kids.

Climate Capitalism: Capitalism in the Age of Climate Change by L. Hunter Lovins & Boyd Cohen

Climate Capitalism: Capitalism in the Age of Climate Change by L. Hunter Lovins & Boyd Cohen

I’ve mentioned I’m an environmentalism nerd, right? One of Hunter Lovins’s previous books, Natural Capitalism, pretty near changed my life. And true story: it was for some time my life’s ambition to work in carbon trading. You know, where companies can buy and sell carbon credits under a cap-and-trade system. Okay, maybe a little obscure for the book crowd.

In any case, the environment might not be the biggest hot political topic of the minute anymore, but I assure you the problems didn’t fix themselves when we lost interest again. This year has actually been a wonderful year for good, readable books on the current and future movements in environmentalism – Tim Flannery’s (most famous for The Weather Makers, but who is also responsible for a fabulous illustrated bestiary of extinct animals called A Gap in Nature) new book Here On Earth also just hit shelves, and Ray Anderson’s Confessions of a Radical Industrialist is at the very top of my must-read pile. I’m happy to report that the serious discussion about climate change has moved beyond fear mongering vs deniers, and is in the happier territory of Okay But What Can We Do, Realistically. I love this territory. I’m a big one for plans of attack.

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton

Beaton’s previous collection, self-published and distributed by Topatoco, was more of a sampler; something thrown together to sell at conventions and get the word out. It was silly successful – Beaton won the Doug Wright Award for Best Emerging Talent and has subsequently been published in the Walrus, the New Yorker, The National Post and, I’m sure, more.

No surprise, she’s been picked up by Montreal graphic novel game-changers Drawn & Quarterly. Drawn & Quarterly produce the most beautiful books, and though I expect their Hark! A Vagrant collection will retread a lot of the same material as appeared in Never Learn Anything from History, it’s bound to be better put together in every possible way. If their previous publications are anything to go by, there might even be a limited edition signed/numbered w/ insert edition. Exciting!

I have my little fingers crossed that they might even have some copies ready by TCAF this May – but just in case, my order is in.

Anyone else want to share? Any upcoming releases have you super excited?

April 1, 2011

The Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book: Digital Reviewing

Last night I attended the 17th annual Gryphon Lecture on the History of the Book for the Friends of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The lecturer this year was the very prolific and always amazing Prof. Linda Hutcheon speaking on, to my delight, “Book reviewing for a New Age”. Well well!

Though Prof. Hutcheon is an academic and the Thomas Fisher is an institution within the University of Toronto, the Gryphon lecture is intended for a “layman” audience of supporters and friends. Unlike so many talks I’ve attended on book reviewing and the internet, the audience here was entirely devoid of persons employed by the publishing industry. These were readers, heavy ones, and especially, readers of print book reviews. So understandably, much of Hutcheon’s talk was aimed at making a case for digital forms of book reviews, and what they offer to readers.

In this regard, she was not tremendously successful. She began with outlining the decline of the print review, giving us a good history of which papers have scrapped their Books sections and why. The reasons given by the papers and by Hutcheon were all economic: it is no longer, apparently, worth it to a publisher to buy advertising at the same rates and quantities in print. The blame for that has been placed on the internet, probably rightly. The same advertising budget now has to include websites like Amazon.com, the lit blogs and the review copies given out through the thousands of social media channels.

The decline of print reviews has been matched by a much larger increase, however, in digital reviews. All signs point to an overall increase, rather than decrease, in engagement with books. Hutcheon explored at length the “economic, political and ethical” implications of this new divide.

I’ll leap ahead to the end in order to justify my opinion that she ultimately failed to make her case, however: no matter how many good points she made about the value of a more democratic engagement with books, or about increased readerships, the discussion never came full circle to re-include the print reviews. Ideally, she argued, print would broadcast the paid reviewer’s specialty: reviews with a “broader cultural scope”; expansive, reflective articles from persons who (ideally) are more professional and accountable than the customer-reviewer of the internet. Which sounds like a brilliant idea, but it doesn’t explain how this is going to be paid for. If publishers haven’t the advertising budgets to maintain Books sections in newspapers across the Western world, I don’t think it matters whether they contain snappy, puffy reviews or expansive, global-scope ones. Who’s paying for it? The internet has split the same dollar, and I don’t see either new money being added to the pile, or the internet losing it’s advertising appeal.

In any case, Prof. Hutcheon made some lovely and eloquent observations about the literary bloggosphere that addressed our weaknesses and highlighted our strengths. Though the most-often cited advantage of internet reviews is the “democratization” of the process – now anyone, anywhere can (and does) have a platform to let their views be known and the “tastemakers” or “gatekeepers” are losing their grip. But Hutcheon rightly points out that more noise doesn’t necessarily mean more dialogue – after all, can it be a dialogue if nobody is listening? Can critics have the same effect on our “cultural consciousness” if the discussion isn’t being broadcast (vs narrowcast) to a large audience? This is certainly a fair critique of the lit blog formula. Regardless of how measured, professional and well-spoken a blogging critic is, if he or she doesn’t have the same impact on the public sphere that the Globe and Mail, New York Review of Books or Times Literary Supplement has, the role of the critic in society is being diminished.

There are many advantages to the fragmented online review scene. It allows readers to seek out and connect with reviewers who share their tastes. Meta-tools like “liking” reviews on amazon.com do provide a way (however flawed) to distill some of the noise into helpful information. The customer-reviewer is an excellent person to consult when your question is “do I want to buy this” rather than “what does this mean” or “how does this fit into a greater cultural context?”

That customer-reviewers are a wonderful marketing tool is pretty inarguable. But are they anything else? A blogger isn’t as much a taste-maker as a taste-matcher; after all the reader can always go to another reviewer if they start to sense that her tastes are diverging from the reviewer’s. Hutcheon advances the suggestion that online reviewers are “cultural subjects” (after Pierre Bourdieu’s “Political Subjects”), meaning that even if they might not be the focus of a cultural turn or shift, they can at least be the subject of the discourse on culture – and I would take this to mean that the bloggosphere as a whole can be spoken of (“the blogs are saying…”) rather than specific blogs. This certainly has an egalitarian feel to it – we the masses making cultural decisions rather than individuals in powerful (paid) positions. Hutcheon suggests bloggers and reviewers are motivated by the reputation economy and by, of course, love of the subject. So perhaps as cultural subjects our impact is freer from the politics of power.

Except, I have to interject, I think that view of the bloggosphere as a rabble of altruistic amateurs happy to contribute freely to the dialogue is at least a little naive. The CanLit blogging scene, for example, is definitely blurring the professional/amateur line. Many of my favourite lit blogs are written by freelance print reviewers, and those that aren’t are written by people who, for the most part, have ambitions of becoming part of the paid “real critic” circle. Their blogs are, in this respect, proving grounds and elaborate CVs for budding writers and journalists who would be thrilled to death to be the next William Hazlit or Cyril Connolly. It seems difficult to escape the fact that the same people who are blogging are the people who are reviewing for the Quill & Quire, the Globe and Mail, writing for the Walrus, Canadian Notes and Queries, and the National Post, and publishing books destined to be reviewed by the same. It’s a small world out there. These are “customer-reviewers” to an extent, but it’s also becoming and increasingly legitimate in-road to becoming a professional critic. Even for those who have not made that leap to legitimacy yet, their contributions have to be read as something coming from someone who does consider themselves professional, even if no money is changing hands – yet.

In any case, the audience of Prof. Hutcheon’s talk seemed interested but unmoved by her arguments for the cultural importance of lit blogs and customer-reviewers. The average age of the audience-member was probably 65 years old, and these are, don’t forget, a self-selected group of people who choose to donate money to a rare-book library. The question period certainly was dominated by incredulity and derision at the state of the print reviews. Still, it’s good to know these issues are reaching even these, the least-receptive ears. The dialogue is spilling out into a wider audience, and it will be interesting to see how the discourse develops as the institution of reviewing continues to evolve.