April 28, 2010

Reading the “Romance” Pt. II

Disclosure: I am a religious, fanatical, avid and loyal reader of Romance novels.

That Alexandre Dumas is worshiped in my household as a sort of hearth-god should have been your first hint; that I’ll blather for twenty minutes uninterrupted about War and Peace to anyone who gives me an opening should be the second. I have space in my heart for Walter Scott, Robert Lewis Stevenson, – maybe not Ryder Haggard -, Hardy and George MacDonald. If a book has conspiracies, chases, sword fights or similar swashbuckling, oaths, irrational acts of honour, betrayals, daring escapes or rescues, I am very likely to read it and love it. Any confusion between my Romances and the Romance novels pulped out by Harlequin can be settled with an assurance that my darlings are also terribly romantic, so the word can be interpreted either way if you like. Or at least they are terribly romantic to me.

I complained a while ago about the lack of romance novels out there for those of us with half a brain. As it turns out there’s plenty of brainy romance available for those of a particular romantic disposition, unluckily I am differently disposed. I said this in front of a room of romance readers recently and they immediately jumped to the conclusion that I was looking for something kinky. This isn’t the case, and I’ve had some trouble putting it into words until now. But my recent reading has clarified the issue.

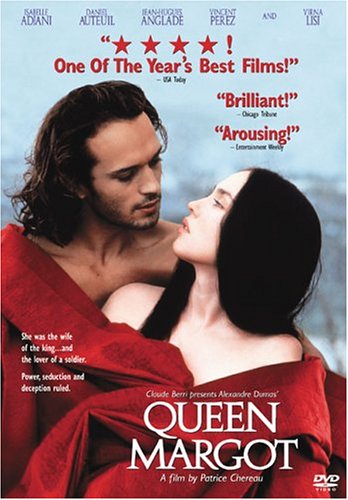

Queen Margot, the 1994 film - admittedly, some of the best eye-candy ever put on film.

I’ve been reading what are collectively known as The Valois Romances, three novels by Alexandre Dumas set in the late 16th century and the Louvre of the Valois dynasty (Francis I through Henry III, roughly). The individual volumes are known by a variety of titles depending on the edition or translation, but the most famous of these is probably the first, known best as Queen Margot. It is best known, probably, because of a very well-received recent film of the same name, La Reine Margot (1994).

The differences between these books and the film align very well with the differences between my expectations of a romance novel, and the Rest of the World’s expectations. The plots of both are similar, if not identical: Marguerite of the Valois, youngest sister to the king, Charles IX, has been given away in a political marriage to Henry, King of Navarre. The kingdom is, at this point, destabilized by conflict between the Catholic institution and the Huguenot population, and Marguerite’s marriage to Henry, king of the Protestants, is supposed to create some kind of stability. It is a loveless marriage, with both parties agreeing to turn blind eyes to the other’s love affairs. Amidst a storm of politics, massacres, and intrigue, Marguerite falls in love with and carries on a passionate affair with a Protestant nobleman named la Môle. As in all of Dumas’ novels, nothing ends well for anyone.

La Môle’s devotion to Marguerite in the novel is complete. Marguerite, in typical Romantic style, is flawless in every way, a paragon of femininity and queenly-ness. At first blush the feminists here roll their eyes, but the Romantics were more fair to their heroines than we are today: Marguerite is cunning, calculated, educated, intelligent and in control, and these are all considered virtues. She is, after all, the Queen of Navarre, and Queens are second to no one. La Môle describes himself as “first of her subjects” and by this he doesn’t mean “the best of them”, he means “first in line to serve her”. And that’s what he does, up to the minute he is killed (sorry, spoiler – but as I say, no hero of Dumas ever escapes this fate!)

The Marguerite of the film is a more complex woman, certainly, but the means by which they’ve “problematized” her are off-putting. Flaws abound. Marguerite is known as the whore of the Louvre, and has been sleeping with (or raped by) all three of her brothers. Unable to secure a lover on her wedding night, she wanders the streets of Paris in a mask posing as a prostitute and eventually “picks up” the film’s la Môle, who boffs her in an alley. She’s uninterested in politics except in so far as they endanger her life, but becomes hysterically moral (and ecumenical) in the wake of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (the Marguerite of the novel is indifferent to the massacre, except in so far as it has shaped politics). But never mind, because the massacre has reunited her with her back-alley-romp, la Môle, with whom she is now smitten. Her past sexual promiscuity is somewhat explained by la Môle’s poetic insight: “She loves as though she is seeking revenge.” In a scene which spoke volumes to me, Marguerite muses that la Môle is now her “subject and Master”. La Môle has a little emo moment over this, and eventually proclaims he is not her subject. This seems to please her, and they go on making love. (???)

What has happened here is the nature of the romantic relationship has been completely upended. In the novel, la Môle worships Marguerite and ultimately gives his life up for her cause. His only desire is to belong to her. In the movie, Marguerite needs a strong hero to save her from her victimized past and la Môle seems is happy to take command of the situation in his strong, usually bare, arms. She belongs to him.

This difference is epitomized in this example, but seems present in some form accross the board. In my Romances, heroes fall in love and spend their books performing great deeds for their ladies, and seem happiest when they can be of some service to them. The women are beyond reproach for anything (except in cases of misunderstandings, which the men with happily flaggelate themselves over later). The drama exists in the plots, intrigues, battles, conspiracies and wars – events in which the women frequently participate. In modern Romances, the women fall in love, spend a lot of time agonizing over some dude, and ultimately are happy when they win the right to be “protected” and commanded by said dude. (At least in my Romances, there’s real stuff to be protected from – kidnappings, assassinations, insults, sword-thrusts…) The women are all kinds of flawed, though the men are not, and the drama is in navigating the relationship. And maybe most typically, in my Romances the ultimate end for a hero is to be allowed to fall on his sword for his love, while the modern Romance has to end happily ever after.

An easy explanation offered to me was that my Romances were written for men, while the modern Romance is written for women. But what does that mean? The women of my Romances are perfect. Who doesn’t want to be perfect? And the men move heaven and earth for them (the Duke of Buckingham starts a war just to get to see Anne of Austria, for heaven’s sake) – isn’t that desirable too? I fail to grasp how nailing down a strong, protective husband beats these as the stuff of day-dreams.

What’s going on here? I can’t decide who needs the literary head-shrinking: me or everyone else. Hopefully the answer won’t be democratically obtained…

One thought on “Reading the “Romance” Pt. II”