July 6, 2009

Review: Frank Newfeld’s Drawing on Type

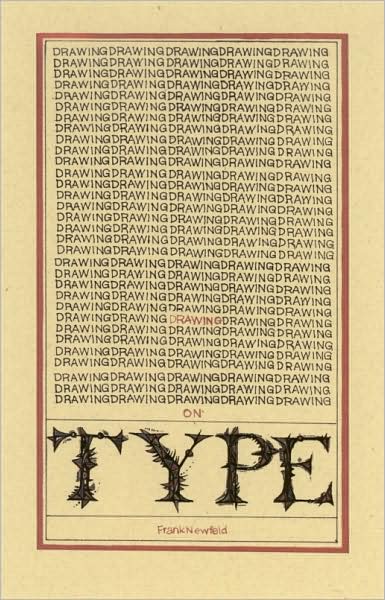

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

I will say this about Frank Newfeld’s memoir: it is gorgeous. The cover was designed by Newfeld himself in types he also designed, while Porcupine’s Quill founder Tim Inkster takes credit for the interior. The paper quality is comfortable, the binding is solid and careful and even the endpapers are well-chosen. This was what originally drew me to the book: its look. Flipping it over and finding the author described as “…one of Canada’s more colouful book-world characters…” clinched it.

Frank Newfeld is an illustrator, book designer, art director and all-around expert in the look, design and feel of a book. He was art director and subsequently a vice-president at McLelland & Steward under Jack McLelland as well as a co-founder of the Society of Typographic Designers of Canada (now the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada). Me, I best knew him as the illustrator of Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie & Garbage Delight, as well as being the guy who judged The Alcuin Society Awards for Excellence in Book Design in Canada. But what becomes evident over the course of his memoir is that he is decidedly not a writer.

I was a little torn about how to approach this review because of that fact. Newfeld has a lot to offer the reader in wisdom, anecdote and experience. That it hasn’t been rendered by a master storyteller doesn’t detract a lot from those elements. His delivery is simple and doesn’t pretend to be more of a stylist than he is, but nevertheless some parts of the book do suffer. The first half of the book is taken up with the first 25 years of his life, most of it spent in the military in Israel. Though he takes some first tentative steps towards his later career as an artist there, the vast majority of this part of the book is a fairly dull, two-dimensional rendering of places and names, the significance of which is not really given to the reader. Names are introduced three to a page, none of whom warrant any character-building. It reads a bit like an acceptance speech, where the aim is to recognize and thank all the influences in a life without giving the rest of the audience any hint of who these people were. This treatment of “characters” lasts for the rest of the book. Almost invariably if someone is identified with a full name it is to “name drop” them and give some laudatory praise, but no description. People who Newfeld is going to speak less well of are discretely identified only by first name, or title.

Even Newfeld himself fails to emerge as a fully-formed personality in the reader’s mind. That said, Newfeld describes the Canadian book trade in very different terms than I think we are used to hearing from those in the know. Unlike the love-in of glosses like Roy MacSkimming’s The Perilous Trade, Newfeld is critical of newer elements emerging in Canadian publishing in the 1970s-1980s. That Newfeld is of the generation prior to the Douglas Gibsons and Dennis Lees of the publishing world is quite evident. There is food for thought for those who would like to question why, if Canadian publishing underwent such a rebirth in the 70s, publishing today looks like a two-player racket pulping out more of the safe and predictable. Food for thought, but Newfeld almost sabotages his credibility with some of his recollections. In particular I found myself flinching through the long blow-by-blow of his difficulties with Dennis Lee and the publication of the children’s poetry Newfeld illustrated. Newfeld’s side of the story is, no doubt, just; but his manner of telling it comes off as petty. He makes nods to being fair and praises Lee when he should, but undermines that carefree tone with smug retellings of some pretty irrelevant incidents. A full-page quote of a bad review Lee garners from the Globe and Mail for one of his post-Newfeld books was totally unnecessary. That he continues to harp back to the same incidents for the next two chapters just reinforces the reader’s sense that Newfeld is being defensive.

Newfeld is, however, at his very best when he is describing a project or a process rather than a person or an event. This, I imagine, is the result of his being (by his account – and I have no reason to doubt him) an excellent teacher who ultimately wound up as head of the illustration program at Sheridan College. The art of design, typography and illustration comes brilliantly to life under his instruction, and his commentary on each discipline is insightful, measured and utterly authoritative. I was especially impressed with his very rational assessment of the use of modern technology in the book trade. I thoroughly expected him to express a curmudgeonly, out-of-date dislike for emerging technologies and found him instead quite open to innovation and experimentation.

This is ultimately what makes the book worth reading – the expertise and care that shine through when he talks about book design and book illustration. He is a genuine connoisseur of material book culture, one with more experience and laurels than many other people alive today. Even when you wonder if he’s being fair to some of the people and attitudes that he criticizes, you see exactly why, formally, he fights these fights. The man understands books in their entirety and is absolutely right when he says publishers are becoming far too focused on the author (and on the design side, the dust-jacket) to the exclusion of the other elements and people involved. This is a debate we don’t see enough of in book circles today. Newfeld is more than qualified to be the one to (continue to) lead the charge and I will, for my part, be taking him to heart in my future academic-and-blogging endeavors. Drawing on Type is a valuable text – and looks absolutely wonderful on my bookshelf.

5 thoughts on “Review: Frank Newfeld’s Drawing on Type”