June 15, 2009

Like Minds: The Triumphs and Trials of Collaboration

Well, first of all let me apologize for the prolonged suspense! This summer holiday went into several rounds of overtime, and I have been caught up in the very busy business of reading in the backyard, meeting with old friends for tea and teaching the little one which rocks, twigs and leaves at the park are best for eating (answer: any). But all good things have to come to an end, and new good things have to be taken up again.

May’s virtual exhibit, Like Minds: The Triumphs and Trials of Collaboration has been an eye opener. First of all, submissions were overwhelmingly genre books, science fiction and fantasy. Being a fan of both genres I can’t say that I mind, though as I wasn’t able myself to come up with many non-genre examples and had hoped you lot out there would be able to jog my memory. Not a lot of luck there, but it does stand out as a sort of mystery to me. Why are genre writers so willing to share a byline, while examples in “literary” fiction are impossible to come by? I don’t have an answer today.

Illustrative Examples

Some of the best collaborations in literature are not, in fact, between two writers telling a story. Great minds exist in other aspects of book-making and often it is their input that brings distinction to a title. In particular we have the illustrator, often that raw creative force whose images inspire the writer to match a story to them. Illustrated books go both ways, after all: for every book that was illustrated after writing, there is one that was written to match the art.

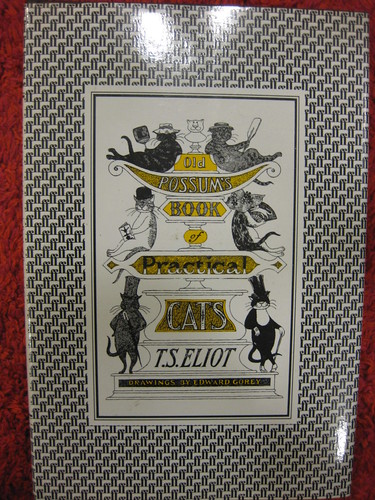

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T.S. Eliot, illustrated by Edward Gorey, Faber & Faber, 1982

Found by me, in my dining room.

Old Possum’s was always a cute book, but the addition of quirky Gorey illustrations made this a hit outside the usual poetry crowd.

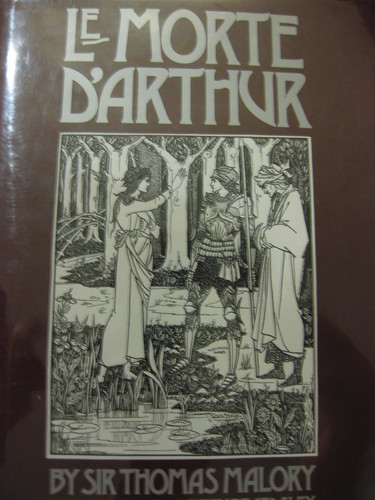

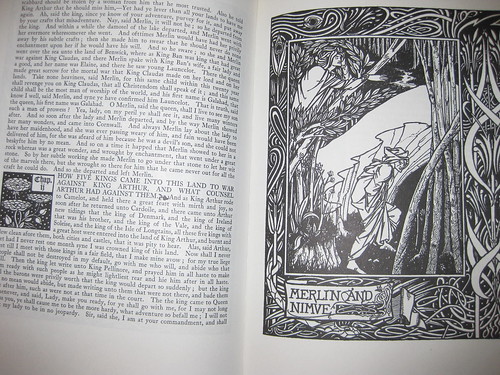

Le Morte D’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory, illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley, Omega Books, 1985

Submitted by Imshan, who bought the book from Contact Editions.

Beardsley’s illustrations of the classic Arthurian legend are almost as popularly well known as the work itself.

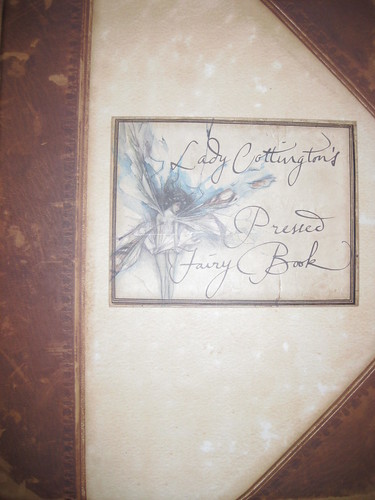

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book by Terry Jones & Brian Froud, Raincoast Books, 1998

Submitted by Lauren, who has it on her shelf.

Although Jones is the man of words and Froud is the man of the brush, the two share credit for this hilarious mock-Victorian compendium of pressed fairies.

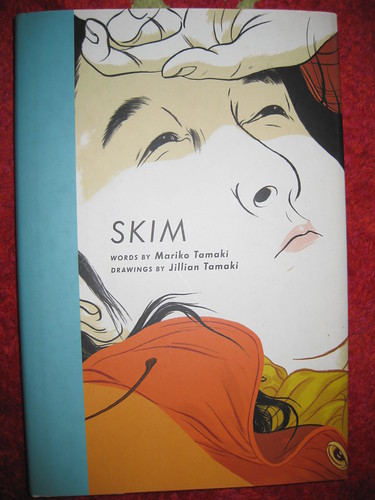

Skim by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, Groundwood Books, 2008

Found by me at Pages Books.

This graphic novel not only won the Doug Wright Award for Best Book, but was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for literature in 2008. Interestingly, only Mariko Tamaki was nominated for supplying the “words”, which touched off a minor scandal in the comics community and led many prominent writers and artists to lobby on Jillian Tamaki’s behalf to have her contribution also recognized, on the grounds that “Jillian’s contribution to the book goes beyond mere illustration: she was as responsible for telling the story as Mariko was.”

Cross Disciplinary Collaboration

It isn’t just illustrators who bring their input to a work – editors, publishers, photographers, translators and executors have got their paws in the pie. The end result is always something different than the author’s work alone could have produced.

Burial at Thebes by Seamus Heaney, based on Antigone by Sophocles, Faber & Faber.

Found in my library.

This is supposedly a “translation” of Sophocles’ Antigone, but poet Seamus Heaney has brought so much of his own art to bear on the work that nobody would dare suggest it isn’t as much his own. I wish I had had time to find more of these interpretive translations, the classical world is full of them: Anne Carson’s work, including If Not Winter, fragments of Sappho, Ted Hughes’ Oresteia and Christopher Logue’s “rewritings” of Homer, including War Music.

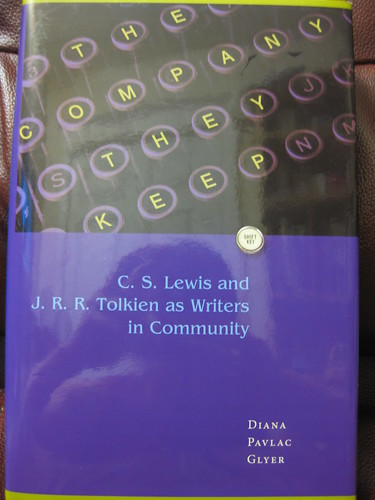

The Company They Keep: C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien as Writers in Community by Diana Pavlac Glyer, Kent State University Press, 2007

Found at The Bob Miller Book Room.

This is my meta entry: Glyer uses the Oxford literary group known as the Inklings as a case study in writers who have worked in community. Importantly, none of the Inklings ever directly co-authored works, but rather met at their local pub to read each others’ work, provide suggestions, criticisms and inspiration. Their influence on each other is unquestionable.

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Good Omens by Terry Pratchett & Neil Gaiman, Corgi, 1991

Found on my husband’s bookshelf.

This is an utterly uncollectible edition, but the work itself is one of the best collaborations in speculative fiction. One of the cases where two heads really are better than one!

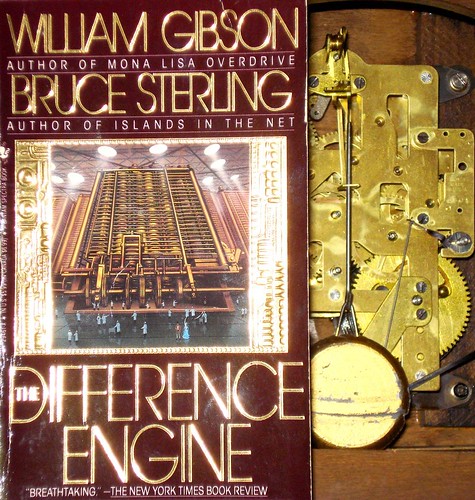

The Difference Engine, by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, Bantam Books, Spectra Special Editions, 1992.

Submitted by Susan, who always provides the best blurbs:

“I had been reading both Gibson (Neuromancer) and Sterling (Schismatrix)

before I heard of this one, and remember being thrilled that the two were

collaborating. The best part was that the subject matter was a Victoria

alternative world combining the two genres, historical and fantasy fiction,

that I loved (such as one of my absolute favorites Little, Big by John

Crowley, and Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke). Come to think

of it, why do so many collaborations seem to scifi or fantasy novels?”

***

Well, that’s it for this month – thank you to my participants, including my sister Lauren who let me bully her into submitting a book I knew she had. The “winner” this month is Imshan, though props to Susan for her “cyberpunk” photo of her cyberpunk book. See you all soon!