May 11, 2009

Collecting (?) Webcomics

My weekend at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival was amazing, despite being severely curtailed by my responsibilities as mother to a 10-month-old. I rushed around picking up everything I desperately wanted, but didn’t have the time to browse for undiscovered gems. Alas. But I have my trove. Once home with it I started sorting it into my library and discovered that three out of my four purchases were printed books of webcomics:

The archivist in me (and all book collectors have an archivist in them) is unapologetic. Webcomics are wonderful daily diversions but are also increasingly sophisticated and memorable media. You want to go back to it, reference it, quote it. And while you might be assured that, don’t worry, it’s hosted safely on a server somewhere, I am not. I need to be assured of a thing’s permanence. I need it at my fingertips.

One of the quirks of book collecting is how we covet the firsts – first editions, first printings, first appearances, first translations. There is an authority conferred on an “original” text which is lacking in subsequent printings. Nevertheless, in the case of literature that first appeared in another media, bibliophiles tend towards the first book version of a text. Dickens, as we all know, first published most of his novels in monthly installments – little folded blue-green wraps that were issued monthly. And while these little chapbooks are valuable (say $2,000 for all the installments of Nicholas Nickleby) they don’t compare to the first edition of the book (about $13,000 for our Nickleby in book form). The works of my dear Alexandre Dumas follow a similar pattern. Though first published in chapters through a variety of Paris newspapers and journals, collectors don’t form lines for old issues of La Presse, but will pay thousands for the Paris editions of the books (or more for the legendary Brussels editions).

Comics, on the other hand, follow an entirely different model. Comic collectors want the first form of a comic, and will even covet first “appearances” of characters in other comics, or sketches on the back of cocktail napkins if they can be shown to be the first time a character took form. Copies of old Golden Age comics will sell for tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars. But the graphic novels – the book-form summaries of a storyline or series of comics – are virtually worthless to comic collectors.

As webcomics gain in mainstream popularity and cultural significance, how they will be preserved by society will become increasingly relevant. And though webcomics at the moment are lumped in with the comics crowd rather than the literature crowd, there is no way they can be collected the same way comic books can. After all, there is no original. Even if you wanted to make a case for collecting the first sketches an artist did before uploading them to her website, this doesn’t universally apply. Many webcomic artists work exclusively in a digital medium (see: the popular Toronto-based comic A Softer World, which is created by Photoshopping text onto digital photographs.)

Collectors of “strip” comic book artists (such as Bill Watterson) have pioneered this problem for us by becoming hybrid collectors. The collectible entity for a “strip” collector is collections in book form – hearkening back to the Dickens and Dumas collectors – and licensed product, as well as any original sketches they can lay hands on. Collectors of webcomics (and there will be collectors of webcomics, even if just institutions preserving them for research’s sake) have this task doubled in importance. Whereas the source material of a strip comic might always be found in newspaper archives, the source material for a webcomic could very well vanish altogether. The internet feels very big and permanent but in reality it just isn’t. Websites go down and servers crash. Redundancy helps to an extent but the authority of the material is badly damaged when a piece is no longer found housed by its creator. “Photoshopping” a comic is too easy when Photoshop was the original means of production.

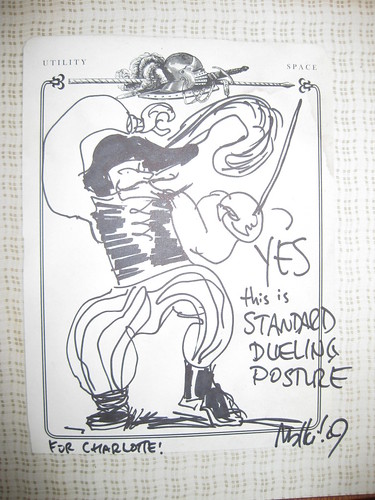

Which brings us back to my purchases of webcomic anthologies. Often self-published by the creators, these anthologies are the highest permanent authority of this material. It helps, too, that some webcomic anthologies are beautifully presented, just as retrospectives of strip artists are (see the recent anthologies of The Complete Peanuts or the new Collected Doug Wright). Artist David Maliki! has even published his latest anthology with “utility space” in which to sketch and personalize inscriptions:

On that note, collecting anthologies of webcomics is also good fun because, unlike writers who will simply sign their inscriptions, comic artists will draw things in your book for you, which is always extra cool.

I overheard a conversation in my local comic book shop recently in which a budding comic book artist was asking the shop owner if he should publish his work in print or online, and the owner recommended “both”. The artist seemed incredulous, but I heartily agree with the assessment. Publishing online is a great way to reach an audience, and webcomics today are exploding in readership and legitimacy. But the print version is essential for posterity, and if done well, will find an appreciative and diligent archival following.