April 17, 2009

Not-so-micro-review of Widdershins

I know I said I wasn’t interested in reviewing books, but I have to post something about Charles de Lint’s Widdershins and as much as it pains me to say so, there wasn’t enough to the book to draw out a longer post. So here we go with the review.

Charles de Lint is an old favourite of mine, a writer who meant a lot to me in high school and who I can still read without flinching too much. I think Fantasy as a genre needs some defenders in literary circles and I had hoped that Widdershins would give me a little platform off which to launch a few rants about the lack of respect the speculative genres get. But Widdershins is not the book to hold as a case-in-point for Literary Fantasy.

Charles de Lint is an old favourite of mine, a writer who meant a lot to me in high school and who I can still read without flinching too much. I think Fantasy as a genre needs some defenders in literary circles and I had hoped that Widdershins would give me a little platform off which to launch a few rants about the lack of respect the speculative genres get. But Widdershins is not the book to hold as a case-in-point for Literary Fantasy.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with his work, Charles de Lint is best known for being the undisputed king of “urban” or “mythic” fantasy. This means his books take place in the “real” world, or one that looks just like it. The fantastic elements are usually gently treated, introduced in appropriate ways and used as metaphors for complex human issues like child abuse, addiction, art or domestic violence. Many of his books, especially the recent ones, take place in and around a city de Lint has created called Newford, and it is with Newford that my qualms begin.

By the time Widdershins was written, Newford has been the backdrop for one too many stories. At this point in de Lint’s career, nearly every character in the city has had a Close Encounter of the Spiritual Kind and they are all entangled in each other’s lives. Despite some backpedaling to explain why Newford is such a mythic hotspot (the spirit realm is closer to the human realm here, magic draws to magic, etc.) the supersaturation of magic has almost trivialized the device. The mystery and metaphor are lost when Newford crossed the line from “real city” to “magical world”. De Lint seems aware of this, and in his preface to the book he offers a sort of apology for coming back to these characters and this story again. But one last story needed to be resolved, he tells us. Fans demand it. So in essence, Widdershins is fan service.

I really wish he hadn’t. Or, at least, I wish I had given this one a miss. The first half of the book (almost 300 pages worth) is loaded down with exposition and back-plot explanations (“Oh yah, that’s Christiana, my brother’s shadow (see: Spirit In the Wires)” or “My sister was a dog and tried to kill me but now we’re cool (see: Onion Girl)…”) and the middle hundred pages are devoted to name-dropping every powerful and awe-inspiring character in the world. De Lint seems to be trying to call up an epic finale to his Newford books by invoking every power he created along the way, but the result of so many “big names” on screen is that they all seem trivialized.

The Big Issue he tackles (aside from Jilly’s abusive childhood, which he already dealt with better in Onion Girl) is a good one – the revenge of the native North American spirits against the invading European spirits (and humans). Restitution for what Europeans did to those who came before them is an entirely unresolved real-world issue that de Lint spins very sympathetically, but the actual plot resolution is weak and anticlimactic. I find it unlikely that hundreds of years worth of seething anger is likely to evaporate the way it did on-page. There’s a lost opportunity here that might have been better handled if it hadn’t been approached in a book that already had too much baggage.

Now, on the positive side of things, there’s no evidence that de Lint has weakened as a writer at all. Widdershins reads like an ill-advised project, but he brings to it the same excellent storytelling and character building that he is known for. De Lint is not a “poetic” writer – I couldn’t find a good prose excerpt to demonstrate his great eloquence because that’s not really his thing. But, probably mindful of this, he doesn’t make any embarrassing attempts at high falutin and flowery imagery filled with misappropriated words and tired old cliches like some writers I could mention. He focuses where his strengths lie: dialogue, character building and action. His characters are so fully realized and unique that I can almost forgive him for coming back to them again and again. It’s hard to leave old friends.

Now, on the positive side of things, there’s no evidence that de Lint has weakened as a writer at all. Widdershins reads like an ill-advised project, but he brings to it the same excellent storytelling and character building that he is known for. De Lint is not a “poetic” writer – I couldn’t find a good prose excerpt to demonstrate his great eloquence because that’s not really his thing. But, probably mindful of this, he doesn’t make any embarrassing attempts at high falutin and flowery imagery filled with misappropriated words and tired old cliches like some writers I could mention. He focuses where his strengths lie: dialogue, character building and action. His characters are so fully realized and unique that I can almost forgive him for coming back to them again and again. It’s hard to leave old friends.

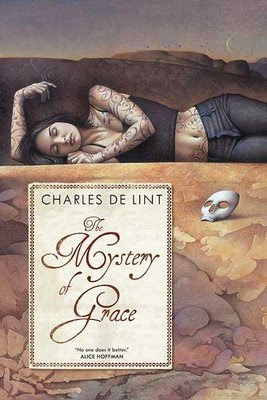

De Lint has a new novel out, The Mystery of Grace, which is entirely self-contained and free from Newford. With any luck this will bring out the best of de Lint’s appeal again. There is no reason why his books shouldn’t stand free of the usual criticisms lobbed at frivolous writers of genre books. He is as good a story teller as Guy Gavriel Kay and Neil Gaiman, both of whom seem to enjoy some mainstream appeal these days. Perhaps I can revisit de Lint later this year and present a review which will stand as a better defense of the genre than the unfortunate Widdershins.