March 17, 2009

Tangential to A History of Reading

This year for a myriad of reasons, I have chosen to read books by Canadian authors exclusively. I had considered opening this blog with a post explaining my decision, but I found the post dull and reasoned that you readers might also. So I will skip onwards and upwards to a tangential point.

I do not intend to review the books I will read. I am not a literary critic or even a student of literature; I certainly approach books critically in my own way but feel I don’t have the critical background to do justice to the pursuit. I am, on the other hand, a prolific reader with a lot of background in a number of other disciplines. So what I propose to do in lieu of a review is to offer a thought (or two, or three…) relating to what I’ve just read. The thought might be critical, might be beside the point, or might simply be something else that the book made me think of. What it won’t be is an evaluation of the book on the whole – that has been done and will be done at length by other people who have a better idea of what they are doing.

The point I want to pursue from Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading will probably speak volumes about why I am not a student of literary theory, since I know what I am about to suggest usually makes actual students of literature turn a bit red and wonder if maybe I’m a philistine. If you’ve read the book (and if you’re a once or future student of literature, I bet you have – it is a favourite on undergraduate syllabi), you’ll find the bit that got stuck in my craw on page 92 & 93. “The limits of interpretation coincide with the rights of the text,” Uberto Eco tells us, and in this case we’re told that Kafka’s “multilayered text” has inspired some 15,000 works of criticism, while the lighter works of, say, Judith Krantz only allow “one…airtight reading”.

The point I want to pursue from Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading will probably speak volumes about why I am not a student of literary theory, since I know what I am about to suggest usually makes actual students of literature turn a bit red and wonder if maybe I’m a philistine. If you’ve read the book (and if you’re a once or future student of literature, I bet you have – it is a favourite on undergraduate syllabi), you’ll find the bit that got stuck in my craw on page 92 & 93. “The limits of interpretation coincide with the rights of the text,” Uberto Eco tells us, and in this case we’re told that Kafka’s “multilayered text” has inspired some 15,000 works of criticism, while the lighter works of, say, Judith Krantz only allow “one…airtight reading”.

What this brought to mind was one of the aspects of David Adams Richards’ Mercy Among the Children that really drove me nuts. In Mercy we meet Sydney, the pacifistic father of three who is venerated in the eyes of his eldest son as some kind of saint, in equal parts because of his honesty and because of his literacy. Sydney, you see, if a self-taught prolific reader who, with no outside input whatsoever, has happened into literary tastes comprised of Western Canon favourites like Tolstoy, Milton and Camus. Despite being entirely alienated from the literary and academic world he has read and understood all that world would have had to offer him.

The idea that any literary work is can be self-evidently superior to another is a bit boggling to me. Yes, of course some works have more depth and withstand the critical readings of an experienced and educated person, but is the presence of those depths an a priori truth that anyone of sufficient intelligence will notice? If you give Swift to an uneducated man living on a desert island, will he necessarily see it as a work of social commentary, or might he be forgiven for thinking it was just an entertaining bit of fantastic adventure?

We’re told in Mercy that Sydney has received the bulk of his books from Jay Beard, another uneducated man who has simply forked over books he has come across in bulk. That Jay Beard has encountered nothing but Keats and Faulkner in his travels as a fisherman defies credibility, so we can presume Sydney must have bought or been given at least a few battered old copies of Shogun or an Ian Flemming novel. Did he just read them once, find the reading “airtight” and use them as firestarter the following winter? Well done Sydney, for tapping into the collective bias of the Ivory Towers without ever having stepped foot in one!

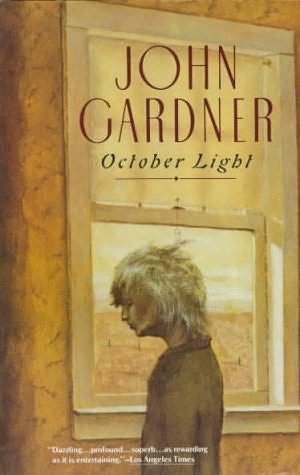

As an alternative to Sydney Henderson’s intuitive grasp of the Western Canon, I’d like to offer the example of John Gardner’s October Light. In this novel, an old man locks his sister in a bedroom where she has no company except for a cheap dime novel she finds discarded in a corner. She reads it to pass the time, knowing it is “trash” because her educated ex-husband had a keen sense of what a “good book” was. Nevertheless, she finds herself finding meaning in every corner of the book, and we as readers are given the same opportunity by the chapters-long excerpts Gardner shows us. The layers of the book are not so much peeled back as they are lain down by a reader who doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they aren’t supposed to bother.

As an alternative to Sydney Henderson’s intuitive grasp of the Western Canon, I’d like to offer the example of John Gardner’s October Light. In this novel, an old man locks his sister in a bedroom where she has no company except for a cheap dime novel she finds discarded in a corner. She reads it to pass the time, knowing it is “trash” because her educated ex-husband had a keen sense of what a “good book” was. Nevertheless, she finds herself finding meaning in every corner of the book, and we as readers are given the same opportunity by the chapters-long excerpts Gardner shows us. The layers of the book are not so much peeled back as they are lain down by a reader who doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they aren’t supposed to bother.

What Gardner is pointing out is that the depth of a novel has almost as much to do with the reader as with the writer – something Manguel knows and repeats in his book. So why, then, does Richards depict Sydney Henderson’s literacy in such bourgeois terms?

Manguel’s aside and Richards’ pretensions with Sydney both make me want to engage in a social experiment. Readers tend to read within a context assigned to themselves from without. Students read books critically because they know they are supposed to. Then they read their beach-books without a thought in their heads because, again, that’s what they are “for”. Even pedestrian readers will get out their pens if Oprah tells them this is a “book club” book and not just ANY old book. What happens, then, if we package Kafka’s The Castle in a glossy mass market edition with a Steven King-esque spooky cover? Or if the course work for your graduate class involved a lot of Clive Cussler in sober, Vintage trade paperback editions? Manguel asks this question early on in his book, when he admits to reading a text according to what he “…thought a book was supposed to be.” Kafka might be a deeper text, but is it self-evidently so, or are many of those 15,000 works of criticism prompted by the reader’s pretensions?

I’m going to read some “trashy” books this year in Canadian Literature, partly, I think, to spite Sydney Henderson. Also to give my powers of interpretation as a reader a trial run – after all, Edible Woman really has been done, hasn’t it? I don’t want to allow a community, however educated, to dictate to me what is going to be deep and what isn’t; what will make me a better human and what won’t. Especially – and this is a rant for another day – with a certain attitude in literary circles that a book isn’t good if it doesn’t make you want to move to Alaska and hang yourself. Despite it being Manguel who has got my pique up, he has also given me permission to assert myself more power over the text as its reader. I’ll take that, thanks, and meander down whatever paths my literary explorations offer me.

I hope it will be an interesting year!

Interesting first entry! Glad to be along for the ride.

I think back (way back) to 1987 when I enrolled at Carleton, in my second of three attempts to live the scholarly life. I signed up for a few courses, purely out of interest as opposed to requirements of the faculty. One was ‘Classical Greek Literature’.

On the first day of the course, the prof gave an introductary lecture that included the words: “There is nothing you can add to the discussion on these works. We will not analyze them ourselves but will instead read what the experts tell us they meant.”

I went straight back to registration and dropped the course.

So, yeah… I have some issues with the Ivory Tower attitudes in certain literary circles as well. It won’t stop be from reading, though, whether what I am reading is ‘high art’ or not.

Wow. My background in studying literature is completely different. My profs all said “There’s been a lot said about these texts. Let’s see if we can find anything new.”

Despite my degree in literary criticism, I have never read Manguel, and based on the information you give, I don’t think I’d agree with his assessment. That said, I think that some books do stand out as deeper and more intelligent, even to those who have not studied litcrit. For example, I knew that Vonnegut was a better and deeper writer that Cussler years before I began studying literature. Some books just resonate more strongly than others.

I found a link to your site from mightygodking.com. I thought your post “Tangential to A History of Reading” was very interesting. I forwarded the link to a couple of my sisters, and we’ve been having a nice discussion about the topic.

Here’s something one of my sisters (with a doctorate in English) said:

“Don’t you think that generally the more experience one has with reading, and different kinds of literature, the better equipped (to start, just in terms–pun intended–of vocabulary, syntax, etc.) the reader is to enjoy more complex works? If a reader doesn’t ‘try’ James Joyce’s Ulysses or Homer’s Odyssey, then he or she may never know that in fact he likes it (or doesn’t like it). For me, trying different kinds of literature is sort of like trying different kinds of food… I didn’t like Moby Dick in college, but I read it a few years ago, and while I wouldn’t reread it again for, say, ten or more years, I could definitely see why other people do enjoy it (and think it’s ‘great’).”

“So there’s the matter of various readers’ tastes; maybe someone (like me) can ‘appreciate’ Melville or Kafka without actually enjoying it to the point of running to the bookshelf and pulling it down every year or so. NOT! While I LOVE Jane Austen’s novels (and could run to the bookshelf every few years or so to reread her novels), I had an undergraduate professor who hated them (he was more ‘into’ Moby Dick, The Sun Also Rises, and A Clockwork Orange.). What I minded, though, was his trying to convince his students, as well as other members of the English department faculty, that Austen’s novels weren’t great literature. Maybe not to him, but he was definitely a voice crying in the wilderness.”

And here’s part of my reply to her:

I think it definitely does matter what the reader brings to the novel. I remember a cartoon I saw once that had a cow in an art museum, staring at a picture, without any caption. I took it as mocking the view that you should be able to interpret/deconstruct art without any context. I laughed long and hard…

That anti-Austen professor would have really disturbed me, although I don’t think I really got into her until after grad school (too many great books, never enough time). How could he not appreciate all the ironies, all the richness, all the social commentary? Did he just think they were simple romance novels?

I’m not saying that a simpler, more approachable book can’t be great, too. My point is that education, or at least breadth of reading, makes it easier to appreciate nuances (and even some really important issues) that might be missed otherwise.

And yes, we all would have dropped the Greek lit professor from Rusty Priske’s comment above like a flaming bag of ****.

I’m glad to have jogged some conversation! 😀 The issue of education and of a specific kind of education creating a particular context is certainly what I think was missing from Manguel’s (and Adams Richards’) idea of literacy. The educated reader brings a deeper reference library with them to the book, so to speak, and can see a text from more angles. But are those angles really there? Will a reader with no, of a radically different, education recognise them?

I wonder about your sisters’ professor’s beef with Austen. I know Austen has been getting “serious” literary attention since Chapman at least (1920s) but I wonder if her literary stock has risen lately with wider acceptance of “women’s ways of knowing” – that is, I know she is critisized in some corners for failing to address Big Issues like politics, colonialism, labour right and whatnot; for treating the period with a bit of a narrow, quaint scope. But those Big Issues are more traditionally “men’s” concerns (power, politics, etc.) Could it be, I wonder, if this professor feels the smaller, feminine, hearth-and-family view that Austen takes is “less” than the tack men take/took?

Oops, I’m making this a feminist issue. Well, maybe it is. 😉

Very interesting posts and conversations. Sadly, I’ve read none of those books.