June 14, 2011

An Oldie but a Goodie

I know, I’m embedding a YouTube video, right? Well, it’s been a slow week.

June 8, 2011

The 2nd National Book Collecting Contest: An Interview with Kieran Fox

Last week the winners of the 2nd Canadian National Book Collecting Contest were announced, and I was fortunate enough to be able to gather a Q&A from each young collector!

Kieran Fox is a 27-year-old psychology graduate student at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, BC. His collection (called Superlative Works from the Subcontinent) is an intriguingly unusual one – these Tibetan-language books were all acquired over two trips to the East in such diverse places as Dharamsala, Lhasa and Kathmandu. Though not a conventional book collector, these works brought together in one place (sometimes transported across borders which considered them contraband) form an impressive whole. He placed 3rd in this year’s contest.

Kieran (right) and Gregory Robert Freeman (left) at the SFU Harbour Centre.

Would you have described yourself as a book collector prior to your fateful West – East trip? What are your usual book-buying habits like?

I never thought myself as a collector of books until recently, though I have been buying and reading them compulsively since the age of about 18. Now I think my book-buying borders on addiction; I buy more than I will ever have time to read, but somehow it is nice to have a personal collection behind your back as you go about your daily affairs. And though I’ll never get to them all, you never know when a particular book might be waiting for you at the right time, and suddenly you will end up reading it and agreeing with everything though it’s been sitting on your shelf for years, untouched.

Have you considered adding to your collection since returning to Canada?

More than that, I have considered making a third trip! And this time intentionally keeping my bag light so that I can fill it up. Dharmasala seems like an ideal place to do this – if and when time and money allow!

If it had been possible, would you have prefered to pick up the texts you did in a digital format?

Not at all. There is actually an immense amount of Tibetan material available digitally online, much of it free – but this has never been the same to me as holding a book, being able to take it out to the woods with you, highlight it, annotate it.

In your essay, you said “A work not worth highlighting, is one not worth reading.” Can I take this to mean you prefer a book to be “personalized” by your use? Can you elaborate on what you meant?

What I meant there was that there are millions and millions of books out there; anyone who is serious about their reading will soon realize that no matter how fast or how much you read, you cannot even begin to scratch the surface – even in English alone! You have to be very selective about what you read, even if you are reading dozens of books a year. So what I meant here is that if you are reading books that you don’t feel you must highlight – that you don’t feel have passages that speak to you and that you would want to see again sometime when you flip through that book in your library – then you are obviously reading the wrong books.

Do you have a favourite book from among your collection? Which, and why?

If I had to choose, it would be ‘The Life of Milarepa’ or the Mi-le Nam-thar in Tibetan. Milarepa is probably the most famous folk hero in Tibet, I think it says a lot about Tibetan culture and people that their greatest hero was a holy madman who went to live in caves and practice Buddhist meditation for his entire life. It is really a wonderful story of falling into darkness and climbing slowly back to the light, all in a single lifetime – it is probably the most encouraging biography I know of.

How did you hear about the National Book Collecting Contest, and how did you initially feel about your odds of placing?

My mother used to be a journalist and reads about three newspapers every day. She noticed the contest ad in one of them and encouraged me to apply when I was home over the holidays for Christmas last year. She suggested that very few people would enter and so my chances would be good and I agreed. But honestly after I sent out my essay I forgot all about it and didn’t really anticipate winning.

Any opinions on how to encourage other young people to take up collecting?

Keep your own collection and your kids will take after you. Our house was always full of books; my mother and father and older brother all read like maniacs. Growing up with all those books around you, and a kid’s natural curiosity, it’s inevitable you will find things you like and I think this is where my love of reading came from. I don’t know if you can instill that in someone later on in life, artificially as it were.

***

You can read the interviews with this year’s 1st place winner Justin Hanisch here, and 2nd place winner Gregory Robert Freeman here!

June 7, 2011

The 2nd National Book Collecting Contest: An Interview with Gregory Robert Freeman

Last week the winners of the 2nd Canadian National Book Collecting Contest were announced, and I was fortunate enough to be able to gather a Q&A from each young collector!

Gregory Robert Freeman is a 26-year-old collector from Surrey, BC. His collection titled The Tudors & Stuarts consists mainly of English history and Protestant theology from the 16th and 17th centuries. He placed 2nd in this year’s contest, and once again I hope you will check out his essay and list once they have been published by the Bibliographical Society of Canada . Mr. Freeman has been very active in Antiquarian collecting communities, maintaining the Olde Documents Repository and the Facebook group Antiquarian Book Collectors which I recommend checking out if you are so inclined!

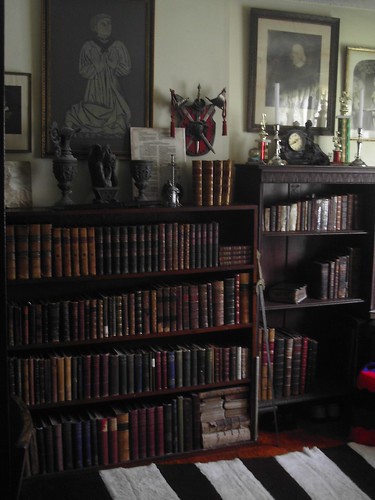

Greg's (gorgeous!) books.

When and how did you realize you were more than just a book-buyer or reader, that you were a book collector? Can you elaborate on your discovery of book collecting as a discipline?

For a time I considered my first $200 purchase as the beginning of collecting rather than buying; but price gives a false impression. Paul Tronson, one of the world’s greatest restoration artists, gave me little bits of advice now and then to raise myself up and collect better books. Doing that was a process of trying to wean myself off cheap periphery items and focus on definite paths with original editions.

Do you have a prefered method of acquiring books for your collection?

For the most part I purchase from my main dealer who only does business by internet and fairs; he often makes acquisitions from London via online auction, and he’ll get something for me by request if I find anything. I search by keywords on abebooks, such as ‘vellum’ or ‘sermon’, etc., with a range of publication dates, and that often brings up some great items. If I’m in the mood for some adventure I’ll go to Vancouver to sift through the mountainous piles at MacLeod’s (they’re strictly brick & mortar).

How do you think internet resources (like eBay, Abebooks.com and online auction houses) have affected book collecting?

eBay and abebooks, etc., have had an enormous effect on book-collecting in the past ten years, and I think much of it good for both collector and seller. It’s rare nowadays that one can ever find an antiquarian bookstore that’s not online (like MacLeod’s). Collectors can pick and choose copies of a title now, where before they might have only found a single copy after decades of searching. A former-bookseller friend of mine (he was recently put out of business thanks to his landlord raising the rent by 50+%) said once to me that antiquarian shops cannot survive anymore without being online. I don’t necessarily agree with that; the larger high-end shops could survive offline very nicely I think, sending out catalogues, such as Maggs in London who has been in business for 160 years. But for the lower end shops, vintage, cheap ‘antique’ and modern all mixed together in a store, the internet has become necessary for many of them and a great source of added income – one that hopefully covers the rent each month. I resort to searching abebooks whenever I’m curious about a certain title and normally I find a copy.

Do you have any other subjects that you “collect”?

I also collect Mediaeval England and handwritten documents of the middle ages to 17thC. Naturally it’s unlikely that I’ll be able to acquire original material of the Saxon period (tho I will try); with the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII tons of Saxon manuscripts were released, and some of those were published by the foremost collectors in the 16th-17thC, one being the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in parallel Latin-Saxon edited by Gibson in 1692. The oldest piece of handwriting that I have so far in my Mediaeval document collection is a land grant from Essex dated to ca. 1270. Most of my documents are of the 16-17thC, typically land agreements, which I’ve taught myself to read; the handwriting on these is gorgeous, and most have wonderful initial letters. Another aspect of my library in general is a small collection of books once owned by prime ministers, with their bookplates, including Canadian PM’s Sir John A Macdonald and Sir Charles Tupper, and British PM Lord Rosebery.

Your collection shows a great depth of knowledge about your subject matter – a subject which is pretty obscure to 21st century laymen. How do you go about researching your books?

I research new acquisitions using other books of mine, with the occasional help from the internet. E.g., In attempting to find out more of Bishop Overall, I searched first the Athenae Oxonienses where I discovered he attended Cambridge, not Oxford, so I looked in the Athenae Cantabrigienses hoping to find him. I still couldn’t. Then it was pure chance that brought a new title, God’s Secretaries, to me, and lo and behold, there was plenty of information, which I compared and supplemented with findings online and in my other books. Overall is a very obscure name to even well read reformation enthusiasts, despite the fact he’s listed as being in the First Westminster Company for translating the King James Bible 400 years ago (of which he must have made a distracted effort, his wife had eloped with a certain gentleman at that time causing great scandal).

If you could add any single book to your collection, regardless of cost or availability, what would it be?

It’s difficult to choose one specific book. Perhaps a Wycliffe bible handwritten ca. 1390 in contemporaneous binding with early ownership inscriptions (about 170 Wycliffe bibles are said to survive).

How did you hear about the National Book Collecting Contest, and how did you initially feel about your odds of placing?

This second contest I heard of from John Meier (Deacon Literary Foundation) while at the Vancouver Antiquarian Book Fair in October. After losing in the first contest a couple years ago I was far more cautious about everything, though I thought I still had a good chance. The months leading up to the deadline were exciting with nail-biting decisions on what major items to acquire on time.

Any opinions on how to encourage other young people to take up collecting?

I’d say to read absolutely everything that comes your way in order to discover your favourite topics and various likes / dislikes. My collection started from buying everything 50-100 years old at a thrift store for 75 cents each, which progressed to older books from bookstores for $10-50 each, and so on. Collecting has been an enormous joy for me, reading, researching, and enjoying what I’ve gathered. For knowledge (even self-knowledge) it may be the most useful hobby in existence.

***

Read my interview with 1st place winner Justin Hanisch here, and 3rd place winner Kieran Fox here!

June 6, 2011

The 2nd National Book Collecting Contest: An Interview with Justin Hanisch

Last week the winners of the 2nd Canadian National Book Collecting Contest were announced, and I was fortunate enough to be able to gather a Q&A from each young collector!

Justin Hanisch is a 27-year-old collector from Edmonton, Alberta currently pursuing a PhD in Ecology at the University of Alberta. His collection on The History of Fish placed 1st in this year’s contest, and though I have had the privilege of reading his entry, it has not yet been published by the Bibliographical Society of Canada so you will have to wait a little longer to see exactly how impressive this collection is! Take my word for it – it’s very impressive.

When and how did you realize you were more than just a book-buyer or reader, that you were a book collector? Can you elaborate on your discovery of book collecting as a discipline?

I was a reader from a young age, but I can remember the first book I bought for both its text and its appeal as an object. I was probably 12 or 13 and found a beat-up, soft cover copy of Jed Davis’s Spinner Fishing for Salmon, Steelhead, and Troutat a library book sale. I no longer collect fishing books, but this book still has a special place in my heart. I bought it because I like fishing, but I also bought the book because the objectappeared to have lead an interesting life. At that moment, I think I became a book collector— someone who buys books for both the text and the object. I like to think I’ve refined my collecting since then, but I’m still very interested in the provenance and individual histories of the books in my collection.

For the past 5 or so years, I’ve started to read books about books fairly heavily. I really like bookseller memoirs and book collector biographies, like A.S.W. Rosenbach’s Books and Biddersand Donald C. Dickinson’s Henry E. Huntington’s Library of Libraries. Reading books like these has really helped me to learn about and appreciate the history of the book trade and book collecting as a discipline.

Do you have a preferred method of acquiring books for your collection?

In theory, book fairs and book stores are my preferred method of acquiring books, but in practice, I have to rely on the internet. Most general shops and regional book fairs don’t have a large stock of old fish books, so I have a variety of regular eBay searches. I also have a few dealers whose websites I frequent and whose catalogues I receive.

How do you think internet resources (like eBay, Abebooks.com and online auction houses) have affected book collecting?

I think the internet has benefited collectors tremendously. It has revealed that a lot of books thought to be scarce are really quite common, which benefits me as a collector through lower prices. The internet has also resulted in a huge flood of books, which previously would have been offered through expert book dealers, being offered by novice dealers. This results in a lot of bad material being poorly described but also results in a lot of good material being poorly described. With thorough research and careful questions, some excellent books can be purchased for very little money.

The internet also makes research materials easily available. The University of Alberta has online access to American Book Prices Current, which I reference frequently. I also make use of digitized books, often through the Biodiversity Heritage Library, to compare books I’m interested in purchasing with other examples. Interlibrary loan is also a great way to request bibliographies and other materials through the internet. I do hate wading through legions of print-on-demand books that flood searches, though.

Did your decision to study ecology (and fish) follow your collection, or pre-date it?

About the time I decided to study fish at university, I decided to refocus my collection from books on fish and fishing to books exclusively on fish. I’ve since sold a lot of my fishing books and put the money toward books specifically about fish. However, I have retained in my collection some specially chosen fishing books that reveal something interesting about fish. For example, I have a fishing book in my collection from 1884 that lists many places in Michigan (my home state) to catch Michigan grayling. The Michigan grayling is now extinct through anthropogenic actions, so the book remains testament to a beautiful species that was wantonly destroyed.

Do you have any other subjects that you “collect”?

Although almost all my collecting budget goes into my fish books, I do have small collections of books about books and first editions of Canadian literature. If money were no barrier, I would rapidly expand both those collections, and I’d love to assemble a library of every book Darwin referenced in his On the Origin of Species.

If you could add any single book to your collection, regardless of cost or availability, what would it be?

There are several books that come to mind. There are some incredible colour plate books like the folio edition of Bloch’s Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische, and Cuvier’s Histoire Naturelle des Poissons. I also covet some early works from the 16thand 17thcenturies. But, I think the one book I’d choose is Rafinesque’s Ichthyologia Ohiensispublished in Kentucky in 1820. The book is rare; no copies are currently on line, American Book Prices Current lists only 4 auction records (three of which appear to be the same copy), and there are very few copies in institutional libraries. So, the book is quite uncommon and also very early for a book printed in North America on North American fishes. But, there is an even more interesting story behind the book. Rafinesque was an acquaintance of John James Audubon and reportedly destroyed one of Audobon’s favorite violins while using it in an attempt to capture a bat. In revenge, Audubon made up descriptions of fictional fish and gave them to Rafinesque to publish in his Ichthyologia Ohiensisas a practical joke. I love this story, and combined with the book’s rarity, I think it’s my “holy grail.”

How did you hear about the National Book Collecting Contest, and how did you initially feel about your odds of placing?

I’m a member of the Alcuin Society, and at the time of the first National Book Collecting Contest, members of the Alcuin Society were ineligible to apply. I saw the second contest advertised in Amphora, and the statement disqualifying Alcuin members was absent. So, I decided to apply. In fact, I was quite excited by the contest and had finished and submitted my entry a couple months before the deadline!

I was cautiously hopeful that I would place in the contest. Books and fish are my primary passions, and as such, I have spent a lot of my time reading about books in general and fish books in particular. I felt I was knowledgeable about books and had assembled a decent collection, so if I could craft a good essay, I hoped that I would place. Needless to say, I was delighted to win!

Any opinions on how to encourage other young people to take up collecting?

I’m not sure it’s fruitful to encourage someone to collect who isn’t already predisposed to it. Of all the people who’ve I’ve talked to about my collection, not a single one has said, “Boy, that sounds like fun, I think I’ll collect books!” That being said, I do see an encouraging number of young people at book fairs and book stores. These young people are the ones likely most amenable to learning more about book collecting as a discipline. I think a “Young Collector’s Booth” could be set up at book fairs to hand out free electronic copies of books on books that are in the public domain (like A. Edward Newton’s Amenities of Book Collecting). The same booth could have a contest to win current books on collecting, like ABC for Book Collectorsor books by Nicholas Basbanes. There is also a large infrastructure of University-level book collecting contests in the States. I think Canadian universities could sponsor similar contests.

It should also be stressed to potential collectors that you don’t need a lot of money to collect books. There are countless under-collected or non-collected fields in which a new young collector could quickly become an authority. Such collections may also serve as important sources for future historians. But, I will echo the advice I often hear: collect something you are passionate about. A successful collection requires a good deal of research, which can be exciting and rewarding in a topic of interest, but tedious without a driving passion. If your passion falls into an under (or non) collected area, then you’ve potentially hit the jackpot!

***

Read my interview with 2nd place winner Gregory Robert Freeman here, and 3rd place winner Kieran Fox here!

June 1, 2011

Treasures from Far Away

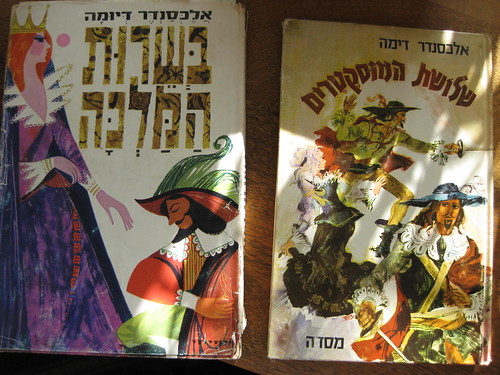

I received a very generous package in the mail a couple of months ago, a gift I’d have blogged about sooner but for the fact that I hadn’t, at that time, any real information about what I’d been given. It was a box of books, all by Alexandre Dumas, and all published in Hebrew.

The sender, a collector of Hebrew children’s books who lives in Israel, had included little notes telling me the literal translations of the titles, but little else. I suppose not much else was needed, but the book historian in me wanted to know more: were the books printed in Israel? Was the art local as well? Are these abridged or complete editions? What kind of things might be added, or subtracted? What makes these books distinctive or representative of where they came from?

So they sat on the shelf at my book store waiting for a Rabbi acquaintance of mine to visit so that I might pick his brain. He did, finally, arrive, but I’m sorry to say he couldn’t give me much more information than I already had. The books didn’t have much more direct information printed on them, and my research is hamstrung by a linguistic barrier. My kingdom to be a polyglot, let me tell you what. But this is an old story in book history circles – we all only read so many languages (in my case, a whopping two) and so the study of literature tends to be pretty localized. Never mind. The books are still beautiful.

The books in the photo on the left are Hebrew editions of The Three Musketeers (right) and something called “Au service de la reine” (left). The latter is not a title used by Dumas for any of his works, and so could be anything from a selection of short stories, to excerpts from one of the romances, perhaps the Musketeers or The Queen’s Necklace. Both are large print editions, and Au service also shows use of vowels, something not typically included in a grown-up book for native readers of Hebrew. The name of the author has been translated differently on one book than the other. To the best of my knowledge, the cover art is specific to this edition.

The books in the photo on the left are Hebrew editions of The Three Musketeers (right) and something called “Au service de la reine” (left). The latter is not a title used by Dumas for any of his works, and so could be anything from a selection of short stories, to excerpts from one of the romances, perhaps the Musketeers or The Queen’s Necklace. Both are large print editions, and Au service also shows use of vowels, something not typically included in a grown-up book for native readers of Hebrew. The name of the author has been translated differently on one book than the other. To the best of my knowledge, the cover art is specific to this edition.

Next, we have a 2-volume edition of The Count of Monte Cristo which looks decidedly more serious. Editions of Monte Cristo tend to, no matter where they are from. I suppose this is because this is one of literature’s most famous stories of uncompromising revenge. Not quite all fun and games for kids, though I hasten to add that The Three Musketeers has its share of tears as well – recall that D’Artagnan’s lover Constance Bonacieux is done away with pretty handily, as is Milady. I have a sombre Spanish edition of Monte Cristo (“El Conde de Montecristo“) that I once felt reflected something of the Spanish character, but I now suspect is more in keeping with most publishers’ interpretation of the story.

Next, we have a 2-volume edition of The Count of Monte Cristo which looks decidedly more serious. Editions of Monte Cristo tend to, no matter where they are from. I suppose this is because this is one of literature’s most famous stories of uncompromising revenge. Not quite all fun and games for kids, though I hasten to add that The Three Musketeers has its share of tears as well – recall that D’Artagnan’s lover Constance Bonacieux is done away with pretty handily, as is Milady. I have a sombre Spanish edition of Monte Cristo (“El Conde de Montecristo“) that I once felt reflected something of the Spanish character, but I now suspect is more in keeping with most publishers’ interpretation of the story.

If you have any idea what this one could be, do share. The title is, literally translated, The Twin Hunters; again not a title Dumas uses for anything. It is a collection of children’s stories about animals. The pictures are often very clearly influenced by 20th century renditions of well-known fairy tales, but are also examples of very early Israeli engraving and printing (circa 1960s). Based on the pictures I found myself doubting if these were Dumas at all, but the work is most certainly attributed to him. Well, who knows? This is the fellow, after all, who penned the version of The Nutcracker that we all know from the Tchaikovsky ballet. If he’d hacked up a version of Sleeping Beauty or similar as well, I wouldn’t be surprised.

If you have any idea what this one could be, do share. The title is, literally translated, The Twin Hunters; again not a title Dumas uses for anything. It is a collection of children’s stories about animals. The pictures are often very clearly influenced by 20th century renditions of well-known fairy tales, but are also examples of very early Israeli engraving and printing (circa 1960s). Based on the pictures I found myself doubting if these were Dumas at all, but the work is most certainly attributed to him. Well, who knows? This is the fellow, after all, who penned the version of The Nutcracker that we all know from the Tchaikovsky ballet. If he’d hacked up a version of Sleeping Beauty or similar as well, I wouldn’t be surprised.

Part of me loves that I have no idea what these books are. It’s all part of the ongoing mystery. I am a wretched book collector in that sense – I don’t have a neat and tidy checklist of specific editions that I intend to buy, I prefer lobs from left-of-field. Put together now, for example, I have 18 copies of The Three Musketeers in five different languages. Nothing would please me more than a whole array of foreign editions, each less scrutable than the last. I do love the universality of Papa Dumas, and the endless diversity of books humanity has produced!

May 31, 2011

An Exciting Day for (Young) Book Collectors

The winners of the 2nd National Book Collecting Contest have been announced! The National Book Collecting Contest awards cash prizes to three Canadian book collectors under the age of 30. This year the three lucky lads were:

The winners of the 2nd National Book Collecting Contest have been announced! The National Book Collecting Contest awards cash prizes to three Canadian book collectors under the age of 30. This year the three lucky lads were:

1st – Justin Hanisch, 27

The History of Fish

2nd – Gregory Robert Freeman, 26

The Tudors & Stuarts

3rd – Kieran Charles Ryan Fox, 27

Superlative Works from the Subcontinent

Links to their prize-winning essays to be added as soon as I can!

***

In even better news, the 3rd National Book Collecting Contest has already been announced! This is heartening news as there was a year “break” between the 1st and 2nd contests in which the continued value of the contest was clearly being evaluated. This immediate announcement, coupled with the news that new sponsoring partners have been added, including ABE Books, CBC Books and the National Post, surely means good things about the long-term prospects of the prize.

May 20, 2011

Your Long Weekend Homework: Books as Ephemera?

Lobbing a heavy one into the crowd today, in case you lot are the sort who prefer to spend a sunny Victoria Day weekend casting bones and mulling over puzzles instead of, say, sitting on a dock in Muskoka sipping lemonade, as I will be doing.

I moan and groan a lot about ebooks and digitization of literature. I know, I’m tedious. One of my main bones of contention with the format is the impermanence of it. Who wants to buy a library you can’t keep? That you will lose to hardware, software, or format changes? That could vanish with the parent company? That can be edited and censored from afar? I’ve always asked these questions rhetorically as if the answer is “Duh, nobody!” and anyone who hasn’t yet come to that conclusion is simply ill-informed. But today it dawned on me – what if nobody cares? Does permanence matter?

I think of how we treat video games. We pay $50-$80 for them. We play them through generally once, but sometimes over and over again if they’re truly beloved. They are unquestionably objects or narratives of cultural value and importance. Yet it doesn’t bother much of anyone when a new video game system comes out and renders all the games you bought for the old system unplayable. If the old disks, rule books and boxes are lost, it’s no big deal. Do you know anyone (anyone sane, anyway) who keeps a library of every video game they’ve ever owned, from King’s Quest and Lode Runner to Dragon Age II? Institutions have been founded which do, of course, archive these things, so they aren’t really “lost”. It’s just the average user who doesn’t care much for the longer term life of the purchase.

What if it were the same with books? What would the cultural implications be of a world where, in general, readers don’t have libraries? Where thousands of copies of each title aren’t passed down from generation to generation? Libraries would, of course, archive them. Collectors would too. But what is lost if the book becomes analogous to a video game – something everyone has for a while, but which is lost and forgotten within the lifespan of the playing device? Would that really be a very big deal?

I have no answer yet. I leave you with this one for the weekend!

May 18, 2011

Style vs Narrative (tangential to Whale Music)

I have long considered myself a Paul Quarrington fan. I started with Home Game, a fish-out-of-water tale featuring an ex-pro baseball player and a band of circus freaks. Shortly after reading that, I met my now-husband who was also, as it turns out, a fan of Quarrington and who lent me Civilization, a fish-out-of-water tale featuring a movie stunt man and a band of early cinema freaks. Then King Leary won Canada Reads 2008 (a fish-out-of-water tale featuring an ex-hockey player and his team of hockey freaks) and I read it too. In the meantime, I bought Spirit Cabinet, Galveston and Whale Music, all for future reading.

I have long considered myself a Paul Quarrington fan. I started with Home Game, a fish-out-of-water tale featuring an ex-pro baseball player and a band of circus freaks. Shortly after reading that, I met my now-husband who was also, as it turns out, a fan of Quarrington and who lent me Civilization, a fish-out-of-water tale featuring a movie stunt man and a band of early cinema freaks. Then King Leary won Canada Reads 2008 (a fish-out-of-water tale featuring an ex-hockey player and his team of hockey freaks) and I read it too. In the meantime, I bought Spirit Cabinet, Galveston and Whale Music, all for future reading.

Whale Music is considered, I think, to be Quarrington’s best. It won the Governor General’s Award in 1989 and was made into a film a little while later. My husband has long teased me for not having read it so this month I finally did. I was unsurprised to find it a fish-out-of-water tale featuring an addled rock star and a wealth of music-industry freaks. Whale Music was a great book, but I fear I took too long getting to it. I had, basically, read it already.

Quarrington’s books share much, maybe too much. The main character is addled – often by addition (booze, drugs). He’s haunted by a trauma in his past, and much of the novel is told in flashbacks. The hero’s memory of the trauma is obscured and avoided, eventually to be revealed after a culmination of smaller, present-day stresses. A motley and colourful cast of weirdos and freaks bring humour and life to the hero’s past and present. Ultimately, all four Quarrington novels I have read have been the same story: redemption and reconciliation with the past. The setting changes, the characters get new names, but the rest stays the same.

The thing is, I like Quarrington’s style. I don’t begrudge him his voice, and I don’t expect him to re-invent himself with each subsequent novel. My favourite authors are typically people with very strong authorial voices and styles, distinguishable from a paragraph. I prefer an authorial voice separate from his story, like Robertson Davies or T.H. White – “Let me tell you a tale…” It works well when the author is a masterful storyteller. There’s something comforting about hearing a new story in the trusted voice of a favourite.

The trouble comes when the author has a strong voice and a distinct style but doesn’t have a new story or, worse, doesn’t tend to write “narrative” novels in the first place. Then we get a real feeling of repetition. This is perhaps why I shy away from non-narrative writers in general. They can be master stylists until the words run dry, but unless they find a way to re-invent their style and voice in every subsequent novel, another 300 pages of the same flowing verse every three years isn’t an attractive read. Certainly they could just keep reinventing their voice. But then, what’s the attraction of “a new novel by…” if it bears no similarity to the previous novel?

I’ve the same reaction to musicians or bands who feel the need to reinvent themselves, by the way – unless the new direction is a genuine organic growth into a new style (like Robert Page’s fantastic newer work with Alison Krauss), the “new” version of an old band often just feels forced and devoid of whatever made them good in the first place. A rare artist is really musically mobile: most of them should stick to what they know.

Quarrington falls somewhere in between. He isn’t a strictly stylistic writer, but his style extends into his plots – he writes the same style of narrative, in the same style of voice. Plot differences keep my attention just enough to give up his books as truly redundant. But I’m becoming disheartened. He had a wonderful voice and was a great writer of funny stories – why couldn’t he pick up a new story somewhere along the way?

But then, where are any of the great storytellers these days? Neil Gaiman, Michael Chabon and I (don’t I keep great company?) have recently written treatise on the same thing: contemporary fiction is losing the art of great storytelling. Style just isn’t enough. Look at Canadian literature’s recent prize-winning offerings. Young first-novelists with a great handle on style and language burst out the gate and wow us all with their debut novel, short on plot, perhaps, but beautifully written! Then they disappear into obscurity as subsequent novels are vaguely praised as promising. Because we’ve already read their story, you see. Now what remains is a stylishness – but what shall it be applied to? If these writers have it in them to be great storytellers, that is an element of their writing which isn’t being encouraged. “Narrative” styles don’t have a great literary reputation. God help you if write a historical novel. A science fiction novel. A mystery, a Western, or something nautical.

I was a little heartened to hear this morning that I am not alone in feeling some great writers are really repetitive. Of course Roth is a brilliant writer – but so what? Why read a new, same-old book when I could read the best of his older books again?

May 17, 2011

On Elitism and Culture

I’m going to describe a phenomenon which I suspect reflects a deep social divide, like left vs right politics, or religion vs reason. There are those who think that literature, like every other art, is something everyone can produce with a little intelligence and hard work, and there are those who think great art is a talent; an unteachable flame of inspiration that only a lucky few can produce. It’s a divide recently exhibited by Elif Batuman and Mark McGurl in their exchange over the value of creative writing MFAs: Batuman feels MFA programs are pulping out legions of under-read hacks (to put hyperbolic words in her mouth – she’s much more even handed than I am), while McGurl feels “a more democratic culture is possible” and that the “workmanlike” literature produced by these programs benefits society in more diverse ways than simply, say, producing a great book.

I don’t think you have to think too hard to see how this same rhetoric is also cropping up in discussions of ebooks vs paper books, most recently evoked by Natalee Caple in this essay for the National Post. “Is this literature, you might ask? No, I do not argue that it is. Instead, it is something more radical. It is free thought; it is democracy.” says she. Ebooks (like MFA programs) have widened the field, and can give everyone a voice.

Putting aside the fact that ereaders, like MFA programs, aren’t actually especially accessible to genuinely disenfranchised people, I think the argument anyone can (or should) be a writer is misguided. Literacy is a beautiful thing and a true pillar of democracy. It lets everyone have access, in theory anyway, to the same ideas, the same education, the same public sphere. It lets everyone potentially in on the important, society-changing movements. The ability to decode texts is absolutely, unquestionably valuable to democracy. And then, for the most part, the right to say whatever you want in the public sphere is also a vital part of democratic life. Voices should not be silenced and marginalized: therein lies control and potential abuse. People should have the right to write.

But let’s be honest here: ebook publishing and MFA programs are not about freedom of expression. They are about producing a marketable product. You don’t enroll in an MFA program because you need to make charges about people in power or because you have a great new approach to irrigation you’d like to make available. There was nothing about the old publishing structure that was preventing marginalized or radical people from expressing their ideas. Plenty of old-school publishers were happy to put their money where your mouth is, publishing revolutionary tracts and out-of-the-way stories. To boot, they’d edit, develop and promote your idea, helping it find a bigger audience than you could have on your own. If your ideas are so out in left field that you can’t find a publisher, well, you could always self-publish them. Even without the money for a vanity publication, you could print your pamphlets at Kinkos.

But it’s easier with an ereader, you say! Is it now? I will tell you something from a bookseller’s perspective: we won’t carry self-published work that doesn’t have proper distribution, no matter how it was printed. Similarly, we’re happy to carry cheap little tracts – so long as they come through the usual channels. I don’t believe for one second that Amazon, Chapters or Apple are much more generous than we are. They will not sell your book if the content offends them. Even if you’re listed, there’s no guarantee of “spotlight” status. “Ranked” search engine results and hard-to-search-for designations like “adult” status can keep your book out of sight indefinitely. Its simply having been published using the right software doesn’t give you the right to be sold through their stores. It’s the same game in the end: whether or not you are read is not about being able to set words on page or screen.

I don’t believe ebooks make voices from the margins any better heard than, say, html documents did back in 1995. Or the photocopier did in 1959. The problem was still how to make people read marginal texts. Will it be easier to get a copy of a marginal ebook than it was to access a marginal webpage? Do MFA programs map a solid path from the classroom to the front table at Chapters? The answer to both questions is of course no.

What they do offer is, perhaps, a better model for getting paid if you are self published. In both cases, however, the path to money has nothing to do with democracy; if anything, it is undemocratic. An MFA program will teach you to write the way publishers want you to. They’ll help you develop a voice that sounds a lot like the big prize winners from the last ten years. Self-publishing an ebook, especially if you do it through (Amazon subsidiary) Lulu, will give you the right to be sold on Amazon.com, the Apple ebook store, or Chapters (unless of course they object to what you’ve written.) Both phenomena might help you get sold (and then presumably read) if and only if you play the game nicely and produce a product they think will sell. On Caple’s continuum between democracy and capitalism, this lands squarely at the capitalism end of the spectrum. MFA programs are a tool to get published and sold, and ebook platforms are a tool to get big chains to distribute your book to be sold.

Booksellers (small and large) might be the “hegemony”, but we’re better representative of readers’ tastes than McGurl or Caple give us credit for. We’re not part of a big machine standing in the way of fresh new thoughts and voices (well, Amazon might be). If a crummy book isn’t being read, it is not our fault. The myth that learning to write program fiction, self-publishing and selling on Amazon is going to bring the limelight to countless marginalized voices is just that: a myth. Readers don’t read at random, and don’t read indiscriminately. Simply showing up in Amazon’s vast database does not guarantee you any more readers than putting up a website or going out to trade shows or press fairs would. If anything, the increased self published noise out there is going to make it harder than ever to stand out in the crowd. You need the bookseller: you need a mechanism to sort through the noise. Booksellers read, Amazon’s search engine does not.

It should come as no surprise to anyone that I come down on Batuman’s side with regard to the creation of great literature too. Not everyone has a writer in them. No creative writing class or self-publishing tool is going to turn any literature student into Tolstoy. The reader has no responsibility, democratic or otherwise, to read mediocre literature. And lastly, democracy does not guarantee anyone the right to make a living doing anything they please. That there are tools available to help people make a buck by buying into an expensive system dictated top-down by corporations isn’t democratic. It’s a pyramid scheme. Nobody is making more money in this system except the people who were making money already. The rest of us are being sold snake oil.

Thanks to Kerry Clare (and her more even-handed approach) for getting me thinking about this this morning!

May 9, 2011

Eep.

Totally blew the budget at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Well, fine! Someone rather eloquently pointed out that ’tis better to buy than to hesitate when it comes to supporting emerging, local, or or self-published creators. This is an economic theory that sounds right to my ears. Should I ever create anything some day I’d certainly appreciate a tendency to buy rather than to hesitate, so let’s just say I’m paying it forward and move on.

What did I get?

Baba Yaga and the Wolf by Tin Can Forest (aka Marek Colek and Pat Shewchuk)

The Next Day by Paul Peterson, Jason Gilmore & John Porcellino

Lose #3 by Michael DeForge (Wish I’d grabbed his now-Doug Wright-winning Spotting Deer as well)

Cat Rackham Loses It! by Steve Wolfhard

Moving Pictures by Kathryn and Stuart Immonen

Entropy #1-6 by Aaron Costain

Catland Empire by Keith Jones

Bigfoot by Pascal Girard

Paying For It by Chester Brown

Sweet Tooth Vols. 1 & 2 by Jeff Lemire

Jeff Lemire Sketch Book by… yah.

Galaxion #2 by Tara Tallan

From Toronto to Tuscany by Kean Soo & um… Tory Woollcott? Forget; apologies.

Northwest Passage by Scott Chantler

Pang, The Wandering Shaolin Monk by Ben Costa

Along with the books and comics was an assortment of bookmarks (I am such a sucker for bookmarks), postcards, stickers, keychains and at least one pair of socks. And I wish I could say I got everything I wanted, but I did not. Time ran out, carrying capacity was reached, and some other logistical difficulties plagued us. I would have bought more prints but for the fact that my house is already full of unframed prints and posters that I can’t work out what to do with. IKEA frames never fit anything! My kingdom for a cheap and easy framing solution.

Needless to say, I had a blast. By the look of Twitter, so did everyone else! There’s no question that this festival is getting stronger as it goes forward, and I am so proud to have it in my own city!