March 30, 2012

My Response to David Mason – Huh?

I really do enjoy my subscription to Canadian Notes and Queries. It is probably my only periodical – outside of Chirp – which I happily renew every year without even having to consider it. I love Seth’s design work. I love the featured cartooning work. I love the often arch and argumentative nature of many of the essays. And I love that they give space to David Mason, really the only space in any Canadian periodical given to an antiquarian book dealer. But,

I really do enjoy my subscription to Canadian Notes and Queries. It is probably my only periodical – outside of Chirp – which I happily renew every year without even having to consider it. I love Seth’s design work. I love the featured cartooning work. I love the often arch and argumentative nature of many of the essays. And I love that they give space to David Mason, really the only space in any Canadian periodical given to an antiquarian book dealer. But,

Dear Mr. Mason,

You lost me with your latest contribution, “Secrets of the Book Trade: Number 1“. I sorrily admit I didn’t understand a word of it. I followed you as far as the admission that antiquarian booksellers are snobs – agreed, and good for you! – but the following generalizations about trade bookselling sounded outright made up.

Which booksellers, pray tell, were you referring to? I’m not sure if you’ve looked around lately, but there aren’t a lot of trade booksellers left, and those still standing don’t bear any resemblance whatsoever to the characture you’ve drawn. “…what they are lacking is knowledge of about 500 years of the history of their trade.”? “new booksellers share with publishers is a certain distrust – even fear – of antiquarian booksellers”? “You order a bunch of books from a catalogue, provided by a publisher, sell what you can and return what you can’t. No risk, no penalty, if your opinion of what might sell is wrong.”???

The above quotes represent three total untruths about trade bookselling featured in your essay.

Just this week Ben McNally delivered the 2012 Katz Lecture at the Thomas Fisher on the topic of Is There a Future (Or Even a Present) for Bookselling? which included a learned history of the book trade. Yesterday I attended new book creator Andrew Steeves‘ lecture on “The Ecology of the Book” which also consisted, largely, of a history of the book trade. Even I am a new book seller and a book historian, not to mention an antiquarian book lover and collector. The booksellers I know – those who remain – are very knowledgeable people who are in no way the peddlers of pap you seem to be describing. I think you and I can agree that Chapters/Indigo is not staffed by “booksellers” so let’s leave out their lack of participation in the larger world of books – unless it was actually that straw man you meant to burn down, in which case I’d feel better if you’d been a little more clear.

We bear the antiquarian trade no ill-will. In fact we continue to foster relationships with used and rare sellers. Our remainder tables continue to be pillaged by scouts and dealers, and we offer deep discounts to some favoured dealers who will take away our overstock by the box. We know that the antiquarian dealers do us the same service we do them – redirecting customers who erroneously visit one or the other of us in search of “nice copies of…” or “cheap copies of…”. I send my customers to you weekly. I hope you do us the same courtesy.

As to this business of publishers’ returns policies giving us a free pass… well, perhaps it is this which stuck in my craw the worst, as I hear it again and again from everyone, customers, academics, and now you, who should know better. The ability to return a limited quantity of books allows us nothing but the merest bit of breathing space. We have to remainder or toss books too. We have to vet the vast, vast floods of new books which are solicited each year into a good, salable collection of which we can return no more than 15% and, even then, which we often have to return at great cost to ourselves in shipping and brokerage – especially brokerage. Choosing which books will sell requires not just an intimate knowledge of every author, publisher and subject we cover, but of our customers and their interests, price points, and whims. Every book we buy is a gamble. Unlike you, who can pick up certain Modern Firsts at a good price without having to think about it, we have to speculate on the market of every book which comes through the door. And we can only be wrong 10-15% of the time.

Further, if we feel a social responsibility to pick up and flog new, upcoming authors and presses with no existing market whatsoever in the name of encouraging local talent and the potential cultural giants of tomorrow, we do so by the grace of this returns policy. Not that we send books back to small and independent publishers – quite the contrary, we have a policy of keeping these books whether they sell or not, out of respect for the limited resources of their publishers. But we can do it because of the returns to larger publishers who can afford it, which will let us free up some cash for zero-gain experiments.

I cannot imagine what point you will eventually make with Number 2 of this series after making such an artificial distinction between booksellers in Number 1. If your intention was merely to point out how very learned you are, I salute you but suggest that you do not become more learned by painting us as less learned. I’d like to suggest that a more useful project might be to make common cause against the real outsider in our field, the entirely algorithm-based online bookseller who is undermining both our businesses by selling entirely unvetted, undifferentiated texts based on price point alone. But that’s another post.

In conclusion, I think you’ll find those booksellers among us who remain in business in this difficult age are a hardy bunch, creamier than whatever booksellers of yesteryear you’re remembering. We each have our bodies of knowledge about aspects of the objects we dedicate our lives to. We are aware of how we compliment each other – have we kissed and made up yet?

Thanks for you time,

Charlotte Ashley

P.S. I would love and prefer a job in antiquarian bookselling. If you’re ever looking for a knowledgeable and neurotically dedicated apprentice, you just let me know.

June 3, 2011

“Extras”

“Value added” is one of the hardest things for me to accept in our consumerist culture. Unlike, apparently, everyone else on the planet, I don’t see a lot of stuff I didn’t ask for as added value. If I want a cup of tea, I just want a cup of tea. I don’t want a 24 oz tankard of tea, even if it costs the same amount. If I’ve just eaten a lovely dinner, I don’t want a huge slice of cake even if it’s the most delicious cake in the world. If I need to get my daughter around town, I don’t need a 45-lb monster stroller with a coffee holder, on-board books and toys and seventeen different kinds of covers for every conceivable combination of rain and wind. Call me old-fashioned. I even knead dough by hand.

The publishing industry is of course in no way exempt from this practice of pushing all kinds of extra stuff on you along with your book. The textbook publishers are the most aggressive with their packages: you can’t buy a thing now that isn’t shrink-wrapped along with a guide on how not to plagiarize, a code giving you access to online content, and a DVD.

We are assured, as textbook sellers, that this extra content costs us nothing extra, but students are extremely suspicious. The most common question we get about textbook packages is “Do I have to buy the whole package, or can I just get the textbook?” Assurances that the cost of the textbook alone would be the same do nothing to calm them. They see the extras as a “hidden cost”. I don’t totally disagree with them, but the cost that concerns me isn’t monetary, it’s environmental. I don’t use the extra material, so it invariably winds up in the garbage. What a waste! The extra packaging used for a class set of 200 copies of a textbook is enormous. But that’s just me.

Trade publications are getting on board with extra content too. Nearly every frontlist literary publication from a major publisher now comes with a reader’s guide, an author interview and “topics and questions” for bookclub discussions. I used to find this addition patronizing but I admit now I’ve become sort of blind to it. One regular customer recently asked me (tongue in cheek, I hope) if he were to tear out the extra material and leave it at cash, if he could have a discount? Even in jest the lurking suspicion that this stuff comes at a cost remains.

In both cases, the extra material provided by publishers is treated, at best, with resigned tolerance and at worst with suspicious anger. I have never, not once in 8 years of bookselling, had a customer pick up a book and say “Oh goodie! A free author interview! I love extra stuff!” So what is this all about? Why are these things being pushed on us?

Part of it, of course, is a publishing industry flailing for something to justify their prices to a public which doesn’t want to think much about real costs. I appreciate this. Maybe the $74.95 they ask for a writing guide will seem less painful if it’s gussied-up with all kinds of extra paper. The $106.95 film text can pretend the DVD that comes bundled with it adds $29.95 of “free” value. (In the latter case, by the way, the publisher is so determined to hide the real cost of the textbook that they refuse to sell the text without the DVD, even if both the course instructor and mediating bookstore refuse to buy the text with it. “But it’s free!” they insist. That the instructor doesn’t like the teaching style the DVD uses or prefers the students didn’t crib their exam answers from the “extra” content is no matter to them. Free is good, right? Who can deny that?) Prices are high and nobody likes that, but maybe if it looks like the customer is getting more, it will hurt less.

This model, though, is wrong-headed. It isn’t working and the simple reason is that the only thing most customers care about is cost. They don’t want the same high prices with more value thrown in, they want lower prices without a lot of bells and whistles. Is this unfeasible? I won’t pretend to understand academic and textbook pricing schemes. Pearson Canada puts the price of every textbook up every year by about $5 even if it’s the same printing of the same edition of the same book they’ve been selling for ten years. Does this reflect a real increase in their costs? I don’t think customers care. They’re furious. A new InfoTrak doesn’t make it better at all. If anything, the extra content looks like an extra cost and customers won’t hear anything to the contrary.

I love colouring these. LOVE.

Some publishers seem to manage to keep their costs lost AND offer useful extra content for free. I’m just in love, these days, with Dover Publications. Yes, these are hideous cheap books often based on old, abridged, and out-of-date texts. But they serve for some purposes and for those purposes they seem to be a great deal. $3 for a real book beats the heck out of a free online document every time. Dover also offers some great online content for, again, free. All you have to do to get free samples is drop in your email address. You can get sheet music, colouring pages, puzzles, short stories, and reference sheets and none of it costs you anything – you don’t even need to make a purchase to go with it. I think this is brilliant marketing because frankly, now my daughter and I are addicted to Dover colouring books and we’ve placed orders for several of them, even though we could just keep downloading and printing out colouring sheets.

The difference is that nothing has been pushed on us. The free content isn’t a condition of a more expensive purchase. We’ve been given a choice rather than being upsold. Maybe I’m splitting hairs here, but for the customer the feeling of control and respect is a big one. People want to know what they are buying and why. “No no, trust me, you’ll love this.” just makes people angry and they feel manipulated. And you know what? If you can lower the price of the book by a couple dollars by leaving out the blasted guide to plagiarism, you’ll be saving everyone money, time and grief as well as the environment. Slap an url on the back page – they can read the plagiarism guide online for free. Even if they don’t buy the book.

May 25, 2011

Blame the Bookstore Month

Another week, another round of articles about the death of the independent bookstore. This round has been precipitated by the announcement that the Flying Dragon Bookshop at Bayview & Eglinton will be closing its doors within a month or two, despite having just won the 2011 Libris Award for ‘Specialty Bookseller of the Year’ from the Canadian Booksellers Association. The tone of the response has probably been shaped by Flying Dragon’s assertion that they simply don’t want to adapt – “at the end of the day we realized that for us, it was all about the books and the tactile, sensory experience they [books] provide.” says their blog.

Last week I responded to Natalee Caple’s assertion that clinging to the old conception of “book” is elitist (or at least hegemonic). This week I see similar claims being made by Amy Lavender Harris over at Open Book Toronto in her article “Authors of our own Misfortune: the Death and Afterlife of Bookselling in Toronto“. They both speak of a resistance on the part of booksellers to embrace new technology. Well, I’d like to address a couple of the misconceptions that seem to underline this stance.

1. Independent bookstores in Canada can not sell ebooks.

I’ve said this before and I will say it again. We aren’t resisting ebooks (much). We’re not failing to adapt. We are simply not able to distribute ebooks. Publishers will not sell them to us. Big ebook distribution schemes like Google eBooks don’t have Canadian rights set up yet (and may never). To sell ebooks bookstores and publishers would need to arrive at an agreement as to how to track, sell, and remit for digital rights and so far, it appears to me as if publishers are not putting bringing independents into the loop as a top priority. Amazon, Kobo, Apple and Google, with their internal programmers, have come up with a scheme for them, and publishers simply need to sign on the dotted line. No independent has the resources to develop such a scheme.

2. Believe it or not, not all customers are clamouring for ebooks.

A short anecdote. Last year we had a professor order through us a book for his course, a collection of Robert Louis Stevenson’s short stories. The only available edition was a cheap, cheap Dover, but it was also available free online. So we ordered far fewer copies of this book than others, thinking students would just read it online or download the ebook. A foolish decision, it turns out, because the students overwhelmingly wanted the “real thing”. It wasn’t the nature of the book that deters customers: it’s the price. When the price is low enough (in this case, less than $3 CDN) they want the real book every time. Converting to a cafe/event space with a few “display copies” of books would not be serving the interests of the customer.

3. “Local” is a geographic term. It has little meaning on the internet.

Everything that makes an independent bookstore great is dependent on meat-space. We curate specific collections tailored to our customers. We provide the service of a conversational, knowledgeable bookseller who knows the stock and can help you find or choose the right book. We bring cultural events into your local neighbourhood.

An independent which goes whole-hog into ebooks isn’t going to be able to offer these things for very long, especially when one of the chief advantages to ebooks is the fact that you can buy them from home, or, really, anywhere you want. I question the value of a “store” which is, essentially, an empty space used for occasional events where a bookseller is made available for advice. Perhaps my customers are unusually skittish, but they want to be left alone to browse and hide in the stacks until they require my advice. If I didn’t offer them books to browse, they’d shop from home. Books have a small mark-up – 20-40%. Driving customers out of the shop would quickly make the space a waste of time and money. Once I am online only, then what? What value am I bringing to my neighbourhood? What makes me different from Amazon?

***

I am beginning to suspect that you can’t have your cake and eat it too. Independent bookstores are a specific business – we are a physical space containing actual humans who sell physical books. Ebook sellers are something else – no space, no humans, and no books. Which is great, but it’s just not the same business. A farmer who decides to sell condos on his land isn’t “adapting”, he’s getting out of the farming business. None of the value of a farmer has been retained in the change.

So, okay, ebooks are fab for a lot of things, like staying in your house, saving your money for some non-book-purchase, and saving shelf-space for some non-book storage. But can we not kid ourselves? There’s nothing to this product or paradigm that benefits someone whose skill, whose vocation, whose livelihood is to know, identify, recommend and sell books. We still have a use, but it’s to offer all those things ebooks don’t require. Maybe the future is better off without this middleman; maybe readers don’t need curators or trusted local experts. That could be. But we can’t be blamed for wanting to maintain our vocations.

ETA: Navneet Alang adds another voice calling for the circumvention of the traditional bookstore. To which I say, the Type/TINARS model is certainly one way to engage in literary culture, but I’d argue that both are supported by a particular set of people. Youngish literary types – writers and publishing folks for the most part or I’ll eat my hat – who enjoy the “scene” and, collectively, can support probably one such store. I’m not convinced the average reader has much interest in carving a social life out of this (hip, trendy) literary scene per se. I certainly don’t. I read books for a lot of reasons, but a big one is because parties and social functions scare the bejeezus out of me and I’m much happier curled up with a book in the company of my family. Again, the skittishness and stoic browsing stance of my regular customers leads me to believe this model would serve, at least, my customers very poorly.

April 15, 2011

The Sadness of Books We Can’t Sell

There’s a depressing side to returns season. It comes near the tail-end of the fiscal year, when we can delay the inevitable no longer and have to send back books which we’d been holding on to as long as possible for sentimental reasons; books which “should” sell. What’s maybe more depressing is that books that don’t sell usually fall into very specific categories, and so maybe as booksellers we should learn simply not to order from these lists. After all, our job isn’t to snobbishly insist readers should be reading one thing or another, it’s to provide them with a good choice of things they might be interested in. So why, after years of failing to sell some of these books, do we keep ordering them? Optimism, I suppose.

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

Young Adult Literature Not Featuring the Occult

This is an especially sad category considering the wealth of absolutely amazing Canadian YA lit being published. I have no doubt that companies like Groundwood Books do stunningly well through the school and library markets, but we sell precious none of them off the shelves. Children’s books – picture books – do very well, probably because it’s parents who buy them. YA fiction featuring vampires, wizards, witches, time travelers and talking animals also do just fine. Classic children’s novels like The Secret Garden, Five Children and It, Swallows and Amazons and so on also do fine (though, again, often purchased by grand/parents).

But good, insightful plain fiction aimed at young adults? Forget it. Not that that stops us from filling the shelves with Glen Huser, Polly Horvath, Alan Cumyn, Tim Wynn-Jones and Paul Yee. We just have to send them all away again at the end of every year.

Chinese Literature

Chinese Literature

Literature in translation goes through fads and phases until a region has accumulated a critical mass of Nobel Prizes or Booker Internationals. These days Middle Eastern literature is starting to come into vogue. And, you know, great! Fabulous books like Al-Aswany’s The Yacoubian Building and Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun are getting well-deserved love, and Tablet & Pen: Literary Landscapes from the Modern Middle East ed. Reza Aslan has been a surprise best-seller for us.

But oh man, China. Its day in the literary limelight has not yet arrived. Gao Xingjian won the Nobel prize in 2000, the first Chinese writer to do so, but I defy you to name offhand a single book of his (I had to look it up on Wikipedia, and even then nothing looked familiar). We do bring the translated books in – A Cheng’s King of Trees, Bi Feiyu’s, Three Sisters, Jiang Rong’s, Wolf Totem and much more – but they don’t go back out again. Tuttle Publishing is even doing wonderful new editions of “Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese Literature” – The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey Into the West – which we have valiantly kept on the dusty shelves these past ten years, to no avail.

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

Post-Soviet Russian Novels

You’ll be surprised to know that Russian literature didn’t die with Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn! Despite forays into internationally renown territory like Victor Pelevin’s contribution of Helmet of Horror to the Canongate Myth series (which also brought us, among other things, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad), I think I’d be safe in saying that post-soviet Russian novels are being completely ignored by Western media, critics and readers.

But there’s plenty to be had. NYRB has published some of the best offerings (though, see below), including Tatyana Tolstaya’s The Slynx and Vladimir Sorokin’s The Ice Trilogy (which I cannot wait to read, for reals). Plenty of Pelevin’s books have been translated and published by big, international publishers. But buyers? Well, not here.

NYRB Classics

NYRB Classics

We don’t sell none of these, so maybe this isn’t a great example. But we do tend to order absolutely everything they publish because their books are so damn good, so when it comes time to return and we’re sending back most of them, it looks particularly bad.

NYRB publishes some truly under-represented bodies of work, like literature in translation outside of your usual Nobel laureates and international bestsellers and literature from the 20s and 30s not written by Faulkner, Hemingway or Fitzgerald. Perhaps, then, this is why they tend to be slow in the selling. It’s hard to sell Elizabeth von Arnim as “frontlist” or “new” when she died in 1941 (and doesn’t have the cheerleading squad that Irène Némirovsky has), even if The Enchanted April is in a beautiful new edition and a wonderful book. People haven’t heard of her, and they’re more likely to pick up the new Cynthia Ozick or Eva Hoffman.

Always exceptions, of course. As I mentioned, Arabic lit is all the rage around these parts nowadays, and NYRB brought us Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih, which sells like those proverbial hotcakes.

Oh well. I suppose if it weren’t these books, it would be something else going back! There are so many books and so little time. Maybe when I finish sending all these lovelies away, I can get to work reading some of the survivors!

March 3, 2011

Returns Season

It’s returns season at the bookstore. It comes for all bookstores: it means our year-end is coming and we need to get as much unsold stock out of the store as is reasonable. I know some big book chains who shall not be mentioned have had, in the past, a reputation for abusing returns privileges with distributors, but for us the right to return is a necessity of survival.

We stick to the rules – we never return more than 10% of our orders to the publishers – and I like to think it benefits everyone. We gain the flexibility to gamble on unknown publishers or authors without fear of getting “stuck” with the book. We can order quantities of books for university and high school courses that might otherwise be foolish (after all, when a prof tells you “I have a cap of 200 students” this sometimes means “… but only 44 signed up”, and nobody would ever tell us. Not to mention the sometimes enormous numbers of students who choose to buy their books elsewhere, use the library, or flat out not read the book. Anyone who thinks university business means guaranteed money is kidding themselves.)

We also have a private policy of not sending books back to certain distributors unless we really have to. We will keep lots of things well past the return deadline because we really ought to have it on the shelf (nevermind that something like Roland Barthes’ Mythologies might only sell once every three years – we should still have it.) We keep small Canadian independent publishers almost indefinitely because we feel bad sending the books back to them. But on the whole, we need to be able to send back a lot of the stock every year to balance the books, clear out some space and cut old losses.

This is a dangerous time of year for yours truly. I can’t send a book back that I’ve had my eye on all year. I have to “intercept” a lot of titles now as I feel it’s my last chance to get them before they go back. And then there’s the sale books – oh yes. Anything that’s past the returns deadline and considered no longer good for stock we cut to 50% or 75% off. You better believe I get first crack at those!

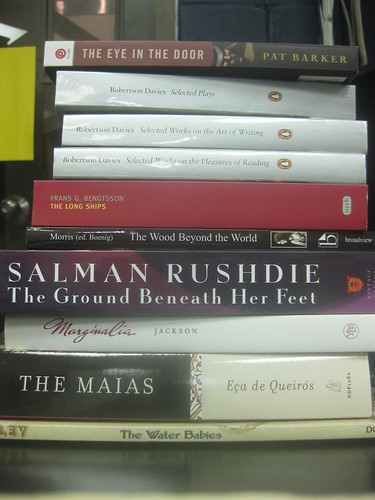

As of this morning, the damage looks like this:

And this is why I’ll never own a house…

November 11, 2010

Will the Reader Wait?

In case you’ve been in a hole (or just not on Twitter) for the last two days, you’re missing a very interesting debate over Johanna Skibsrud’s Giller Prize win for The Sentimentalists. Her publisher, Gaspereau Press, is on the record as saying they won’t take any extraordinary measures to meet the demand for the book: they will continue to print the books as they always have and fill orders as they come. This means an output of about 1000 copies a week. Given a “normal” Giller winner can expect to sell 60,000-80,000 copies, there is some debate over whether Gaspereau is robbing Ms. Skibsrud of a potential windfall.

It seems to me that the crux of the debate is whether or not the reader will wait. Do those books need to be on shelves next week? Or will the readers wait to read them when they can eventually get a copy? If Ms. Skibsrud will find her 75,000 readers over three years, that’s no big loss to anyone. But if the delay causes reader interest to wain, everyone stands to lose.

I am spectacularly naive about what generalizable groups will do. I can’t speak for “The Readers” anymore than I can speak for “The Voters”, whose motives and actions I manage to be blindsided by every. Single. Time. I don’t know if The Readers will wait, but limited evidence seems to suggest that they won’t.

Everyone I know was reading Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall last year. Nobody is reading it this year. The book hasn’t gotten any worse, in fact by all accounts it is ten time the book that Finkler Question is. Maybe everybody read it already? We aren’t selling the paperback of Linden MacIntyre’s The Bishop’s Man, last year’s Giller winner. We only sell Late Nights on Air to students (who read it for Canadian Literature) and I’m not sure we even have a copy of Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures in stock (ETA: we do, one copy, which has been there since 2007).

Actually, our customers don’t even look at our Canadian Literature shelves. They look at New Releases. I don’t think this is because they have already read everything in Canadian Literature, but I could be wrong. I have on occasion experimented by placing a new copy of an old book on a New Release display. This is a good way to sell books which have otherwise been sitting, gathering dust, for five years. Any bookseller can tell you this. Having your book “on display” rather than on a shelf is the best a writer can hope for, because the Reader seems to be drawn to shiny newness. Even the independent reader wants to be In The Know.

I hope for Ms. Skibsrud’s sake that Gaspereau is right, and the readers will wait for her. Certainly some will. With any luck that number will be enough to pay off her student debts and buy her a year or two of leisure time in which to write another beautiful book. If we need anything in Canada, it’s a solid class of working writers, undisturbed by a second “day job”. I have my fingers crossed for you, Johanna. I hope I’m as wrong about readers as I am about everything else people do.

November 9, 2010

A Quick Plug & My Thanks

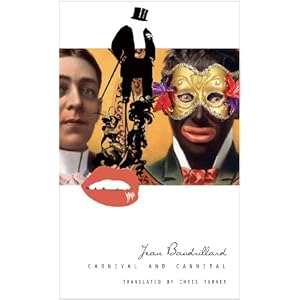

One of my new favourite publishers is Seagull Books, the publishing-wing (pardon the pun) of the India-based Seagull Foundation for the Arts. These books have recently become available in North America via the University of Chicago Press, and each and every one of them that I have seen has been a thing of beauty.

They publish mainly on “the arts”, but within that cachet are a great many profoundly important thinkers. Among their published authors are heavyweights Adorno, Baudrillard, Todorov and Antonin Artaud. The books feature beautifully designed covers, heavy decorative endpapers, dust jackets of odd materials and good paper stock. They come in a plastic slip ensuring your book looks fresh off the press at the moment you buy them.

I’ve held off recommending them until now because the books did, however, have one (or possibly two) major drawbacks: many of the volumes use a heavy, coarse black material for the endpapers which reeks and stains. The first thing you’ll notice when you pull the book out of the plastic is an overwhelming chemical smell. The next thing you’ll notice is that the black “paper” feels as if it’s rubbing off on your hands. Over time the smell does dissipate, but the paper (and this might be the fault of the book’s paper too, not just the endpapers) bulks and warps, and the book will never again lie flat. Perhaps this was the early function of the plastic cover: to keep the book book-shaped.

BUT. I am thrilled to observe that the latest printing of Baudrillard’s Why Hasn’t Everything Disappeared? has addressed these problems. The black endpapers are gone, replaced by a nice textured beige material which doesn’t stink at all. The book opens and closes more easily, indicating that the paper might not be as stubborn. Everything that was good remains while all that was offensive is gone. Form seems to have caught up with function and now I am pleased to encourage you to seek these books out at your local bookstore, even if only to look at what a beautiful book can look like.

November 2, 2010

One Big Question I Have About eBooks

Today I had a bookselling first: a customer asked me if we could sell him an ebook. I knew the answer was “no”, but upon further reflection I realized I have no idea how we would even go about doing such a thing. So I’m gonna ask the crowd to field this one. Please help your friendly local luddite-cum-indy-bookseller here.

Can I sell ebooks? I mean, can any old indy bookseller even sell ebooks? Are these just products publishers produce strictly for device sellers? When we talk about “going to ebooks” are we actually saying “all future bookselling will be done by electronic gadget manufacturers?”

When I look through a publisher’s catalogue, they often give ebook ISBNs. Who can order those? What gets delivered to a bookstore (or chain) when they order that ISBN? Does one need special hardware to sell ebooks? I mean, how are these things delivered anyway? Does one need a dedicated server to store them? Does one ever have them in “inventory” at all? Does one need a machine that prints out codes?

What format does an ebook come in? I gather each reader, unwisely but true, has its own format thus far. What format would a bookseller get the ebook in? Can I sell both to Kindle users and to Kobo users? What format does the ebook ISBN refer to? Do publishers produce separate pdf & Kindle editions? Has anyone ever noted any textual difference between them?

Can a customer “return” an ebook the way they could a real book? Well, can they?

Wow, I really need an ebook 101.

October 22, 2010

Dear Publishers: It’s called a “slipcase”.

I’m thrilled to death that publishers are getting behind fancy private library editions; big, beautiful hardcover tomes for display or general celebration of bookness. We’ve had a particularly meaty month at my bookstores – doorstoppers are coming fast and furious. Northwestern University Press has published an all-in-one edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, translated by the ubiquitous Burton Raffel. Yale’s Autobiography of Mark Twain – volume ONE of THREE – weighs in at about 700 pages. We continue to sell out of copies of Joseph Frank’s 1000-page abridged (from 2500 pages) edition of Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time.

I’m thrilled to death that publishers are getting behind fancy private library editions; big, beautiful hardcover tomes for display or general celebration of bookness. We’ve had a particularly meaty month at my bookstores – doorstoppers are coming fast and furious. Northwestern University Press has published an all-in-one edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, translated by the ubiquitous Burton Raffel. Yale’s Autobiography of Mark Twain – volume ONE of THREE – weighs in at about 700 pages. We continue to sell out of copies of Joseph Frank’s 1000-page abridged (from 2500 pages) edition of Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time.

I love big books, I do. I have a probably unhealthy attraction to works that exceed 500 pages; the more the merrier. But if I may – as a bookseller and a collector – make a suggestion? These books look lovely sitting flat on a table, but as time passes they inevitably make their way to shelves where they must stand upright, or into paperback editions where they are nearly as thick as they are tall. They puff-up, tilt and sag. The Pevear and Volokhonsky War and Peace published by Knopf published in 2007 is probably a case in point – in paperback, the book inevitably looks old and used after a mere two weeks on the shelf. It is too big. The binding – especially in paperback – can’t hold shape with so many pages.

This is an easily remedied problem. It’s called a slipcase. You’ve seen them before, a nice cardboard sleeve that hugs two or more volumes together in one tight box. Penguin released a beautiful trade version of The Arabian Nights translated by Lyons & Irwin in 2008 which housed three hardcovers in one slipcase. See how manageable each volume is? No slipping, sliding or flip-flopping around. No puffy, humidity-soaked pages or disintegrating “perfect” binding. And one wide canvas for all your design needs!

You can have your cake and eat it too: all-in-one editions without asking one binding to hold all those pages in one. And wouldn’t it be nice? A 3-volume slipcased edition of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy? Davies’ Deptford Trilogy? Penguin, please, bloody Clarissa? We will all thank you for it.

October 20, 2010

Again with the Digital Books

Last year I posted in some depth on the subject of academic ebooks – a different subject entirely from frontlist/trade ebooks, let me state right up front. We’ve had some difficulty selling digital books, and I thought I’d update for 2010, with a view on providing some data to academic ebook publishers.

IT ISN’T WORKING. Whatever you are doing, stop. This year, like last, digital “codes” for textbooks was a COMPLETE BUST. Of one title, we have sold to date 750 traditional textbooks (which include the code for the digital book), and 2 copies of the “code-only”. The response at the cash is overwhelming – absolutely nobody wants to pay $55 for “nothing” – a piece of paper that gives them access to information for 12 months. They are willing to pay extra to “get something”.

Similarly, we thought we’d experiment this year with shorting orders of books which could be found online for free (the texts of which can be found at Project Gutenberg or similar). Students want free books, right? They love technology? Once again, the response was overwhelming in favour of “real” books. Paper books of open-source texts are so cheap anyway that students will pay the $3-$11 to get that “something”. About the texts online we hear you “can’t make notes”, “I don’t like all that scrolling”, “At least I get to keep it this way”, etc. The ephemeral nature of an ebook is not lost on these kids. There is a value to permanence.

Now, there are things that could be done to encourage the sale of the digital book. The paper books could be sold *without* the digital codes thrown in for free. Given the ultimatum, more students might go for the digital book over the paper one. Make the digital texts better suited to printing – that might help too. But I ask myself, why?

For what are we trying to force digital books on the unreceptive audience? And I do feel like I’m forcing the issue. Whether it be sending students away when we sell out of a book, telling them to “read it online” (one student has just now informed me that she wants the real book because they can bring a text to their open-book exam, but not a print out. Another consideration.) or desperately explaining that the “Infotrak” online content isn’t costing them anything extra, and no, they can’t buy it without it; selling students on the idea of digital media is like pulling teeth. The instructors aren’t onside either – we had one case where we had to send back 350 copies of a textbook because it came bundled with a DVD & online content the instructor didn’t want, and the publisher couldn’t understand why. (There we sat on the phone having the most unproductive conversation: Them: “But it’s free.” Us: “But they don’t want it.”)

Why are we doing this? Audience reception is part of what has always made me uneasy about ebooks. Aren’t we putting the cart before the horse? Was there some great need for a new way to read texts, thus came the ebook? Were readers clamouring for this technology? No, technologists came up with something new and they’re trying damn hard to sell it. Publishers are a wreck, bookstores are panicking and readers are grudgingly trying to find a way to like the technology. The only people who are happy are the technology manufacturers.

But another year, another step closer to the supposed internet generation. Maybe next year will be the big year for digital delivery of textbooks. Or maybe it won’t. Maybe now that the shine has worn off, we can start having a serious discussion about what constitutes value added. Right now the product we see looks like ill-considered trash to be thrown out with the cellophane wrapper. Or maybe if the technology manufacturers are so keen on a Kindle in Every Backpack, they’ll start bundling those for free with the texts. Just a thought.